Coffee

Culinary Archive Podcast

A series from the Powerhouse with food journalist Lee Tran Lam exploring Australia’s foodways: from First Nations food knowledge to new interpretations of museum collection objects, scientific innovation, migration, and the diversity of Australian food.

Coffee

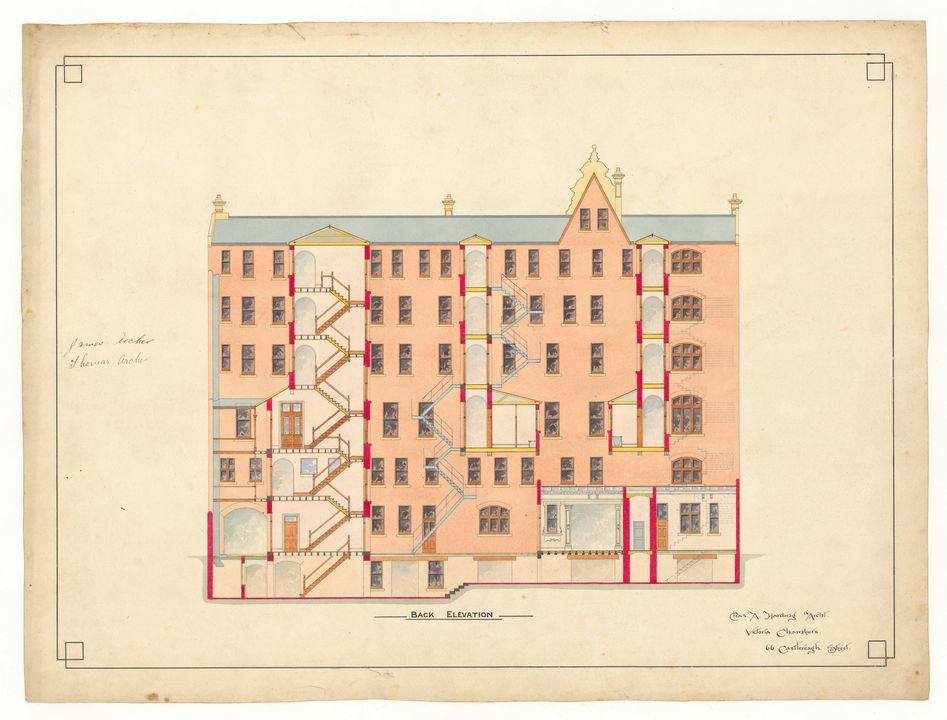

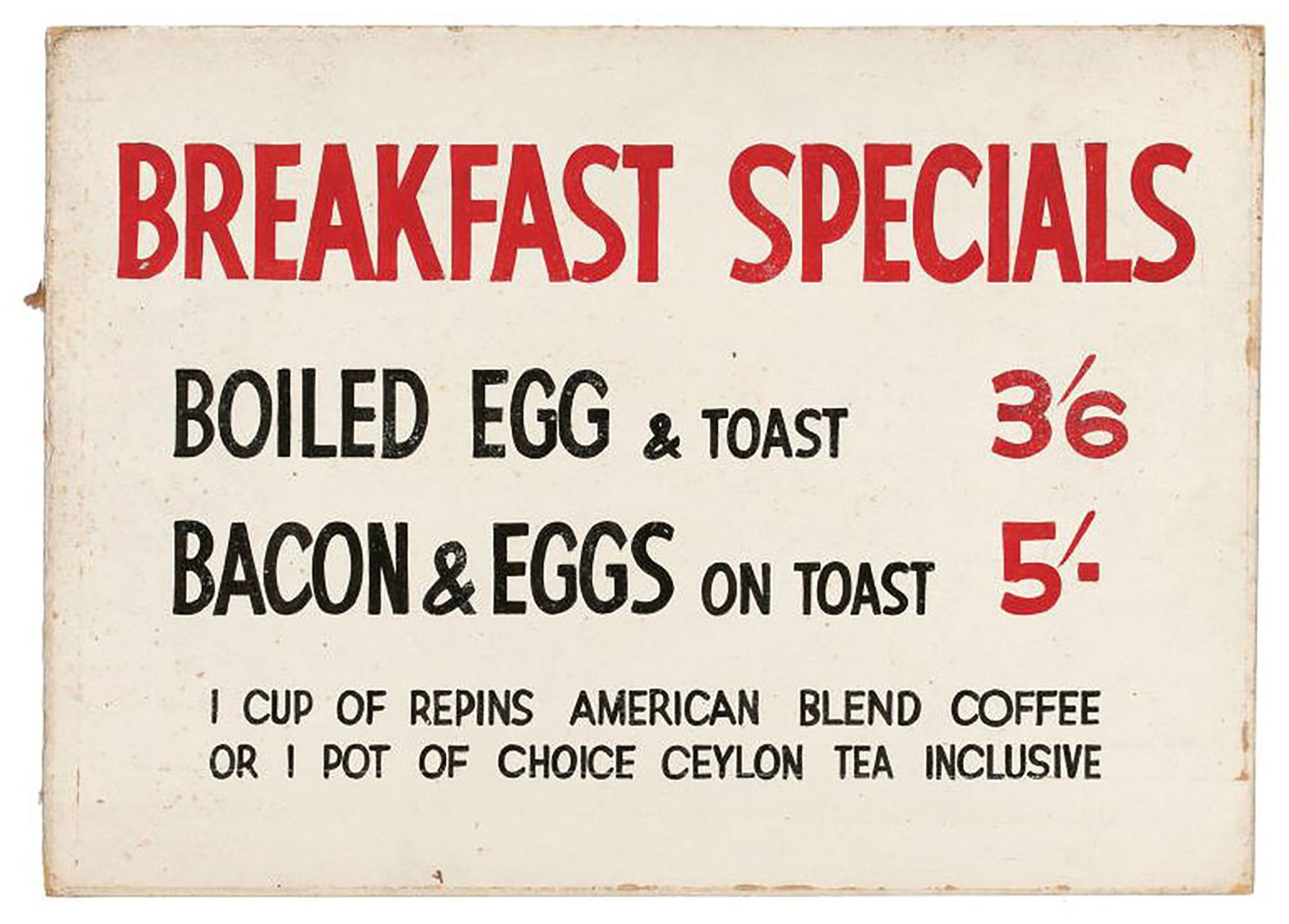

Australia is famous for its coffee culture. Our espresso obsession kicked off during the temperance movement and the subsequential coffee palaces, and then the influential Depression-era coffee shops run by Russian migrant Ivan Repin. The impact of Italian-Australian migration can’t be denied though: it's paved the way for an inclusive coffee culture that includes Ethiopian coffee ceremonies and Indigenous business owners presenting native ingredients and reconciliation in a cup.

‘There were no seat belts or anything like that. So, we’d just bounce around in the back of these Kombi vans with the odd escaped coffee beans flying around with us.’

Transcript

Lee Tran Lam The Powerhouse acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which our museums are situated. We pay respects to Elders past and present and recognise their continuous connection to Country. This episode was recorded on Gadigal, Dharug, Wurundjeri and Bundjalung Country.

My name is Lee Tran Lam, and you're listening to the Culinary Archive Podcast, a series from the Powerhouse. The Powerhouse has over half a million objects in its collection; from an Anglo-Indian coffee pot from around the late 1700s; to photos of mid-century cafes, designed by Hungarian migrants; to the ‘Cafe Bar Compact’ hot drink dispensing machine from the 1970s, the collection charts our evolving connection to food.

![Coffee maker, metal, [Australia], c 1880](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/wkgts1b4/production/b8931085778c239d859bbb5e3e5d83f4fb54ae5e-2000x1335.jpg?w=1920&h=1280&q=82&fit=fillmax&crop=entropy&auto=format)