Seaweed

Culinary archive podcast Season 2

Join food journalist Lee Tran Lam to explore Australia’s foodways. Leading Australian food producers, creatives and innovators reveal the complex stories behind ingredients found in contemporary kitchens across Australia – Milk, Eel, Honey, Mushrooms, Wine and Seaweed.

Seaweed

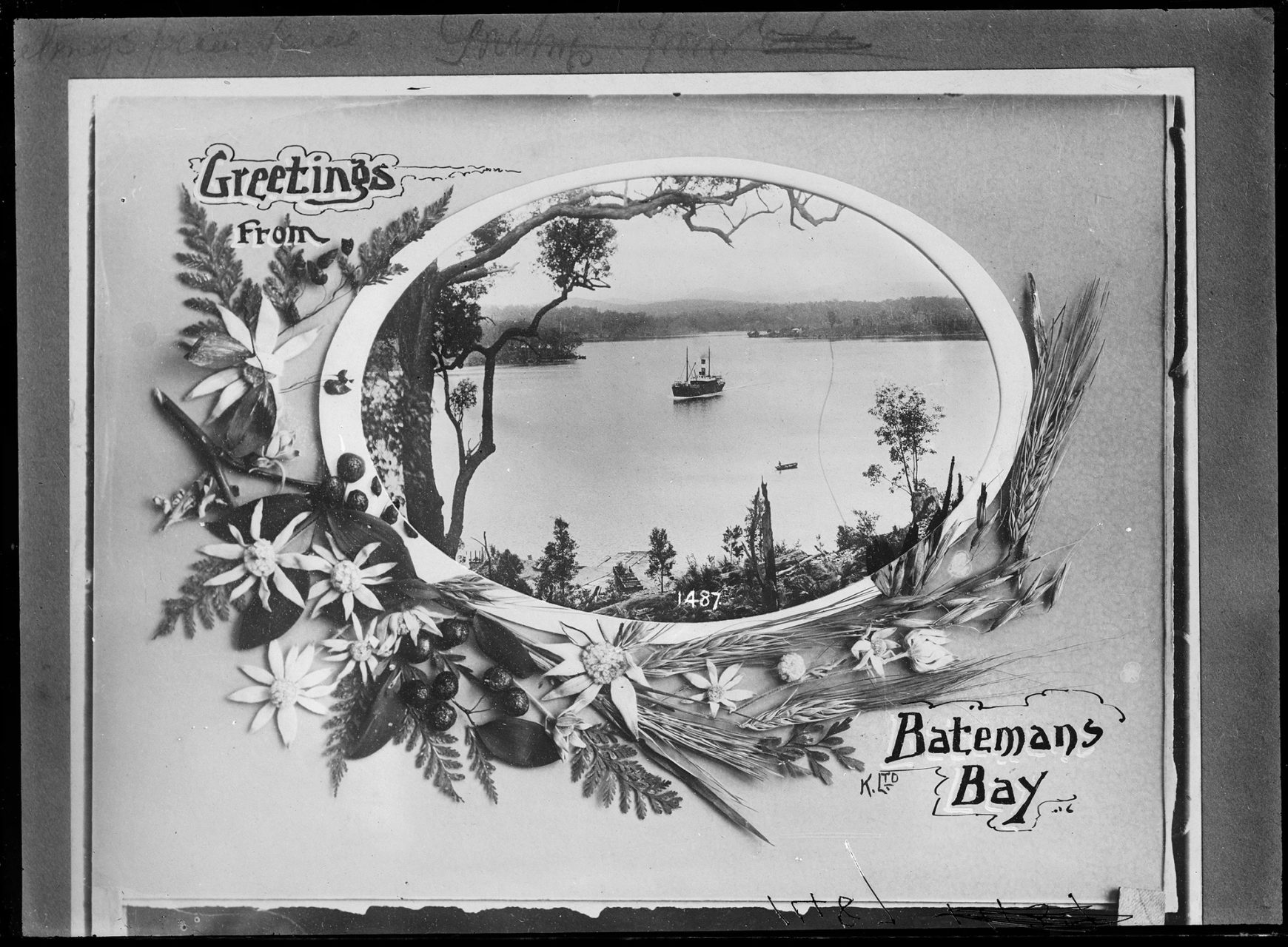

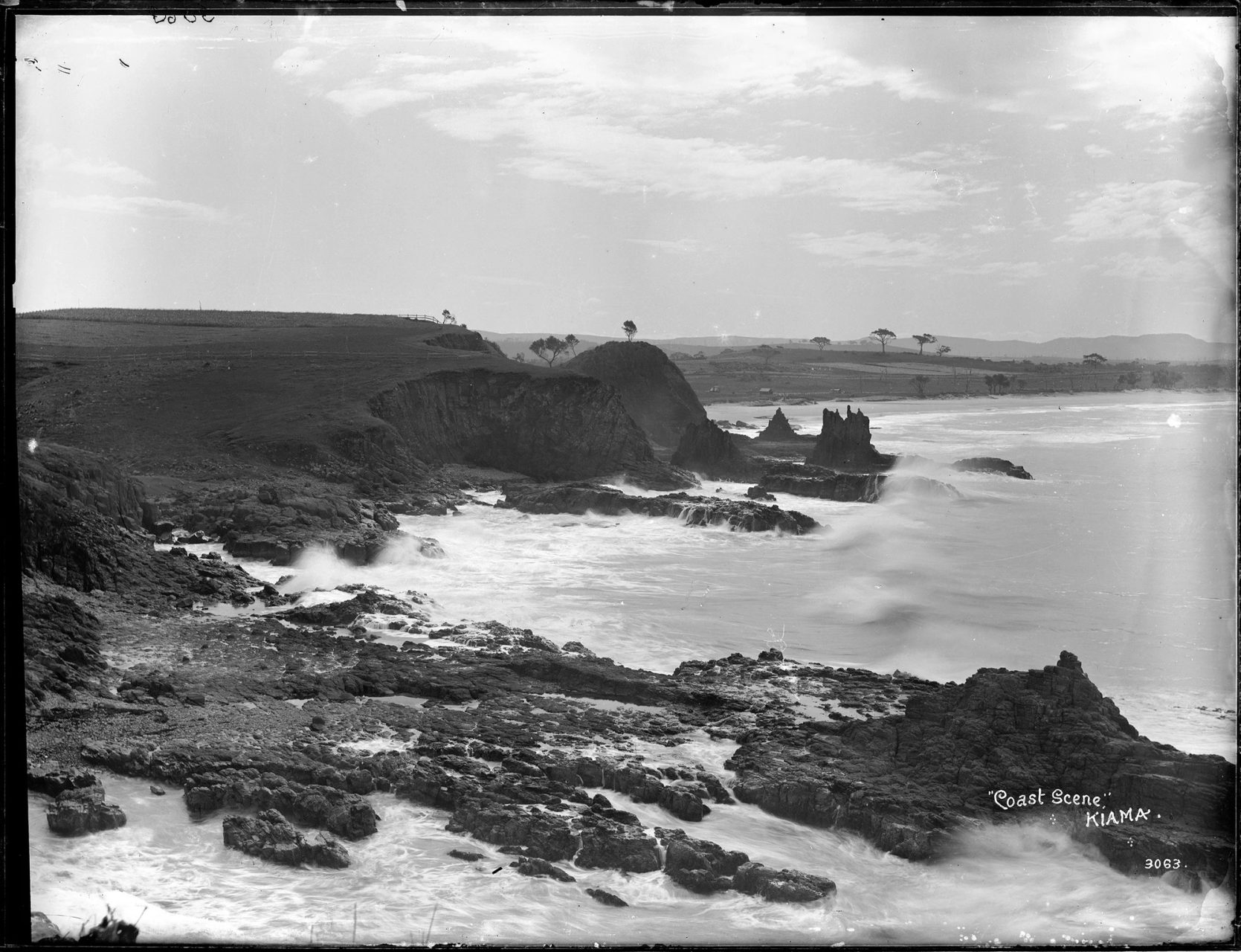

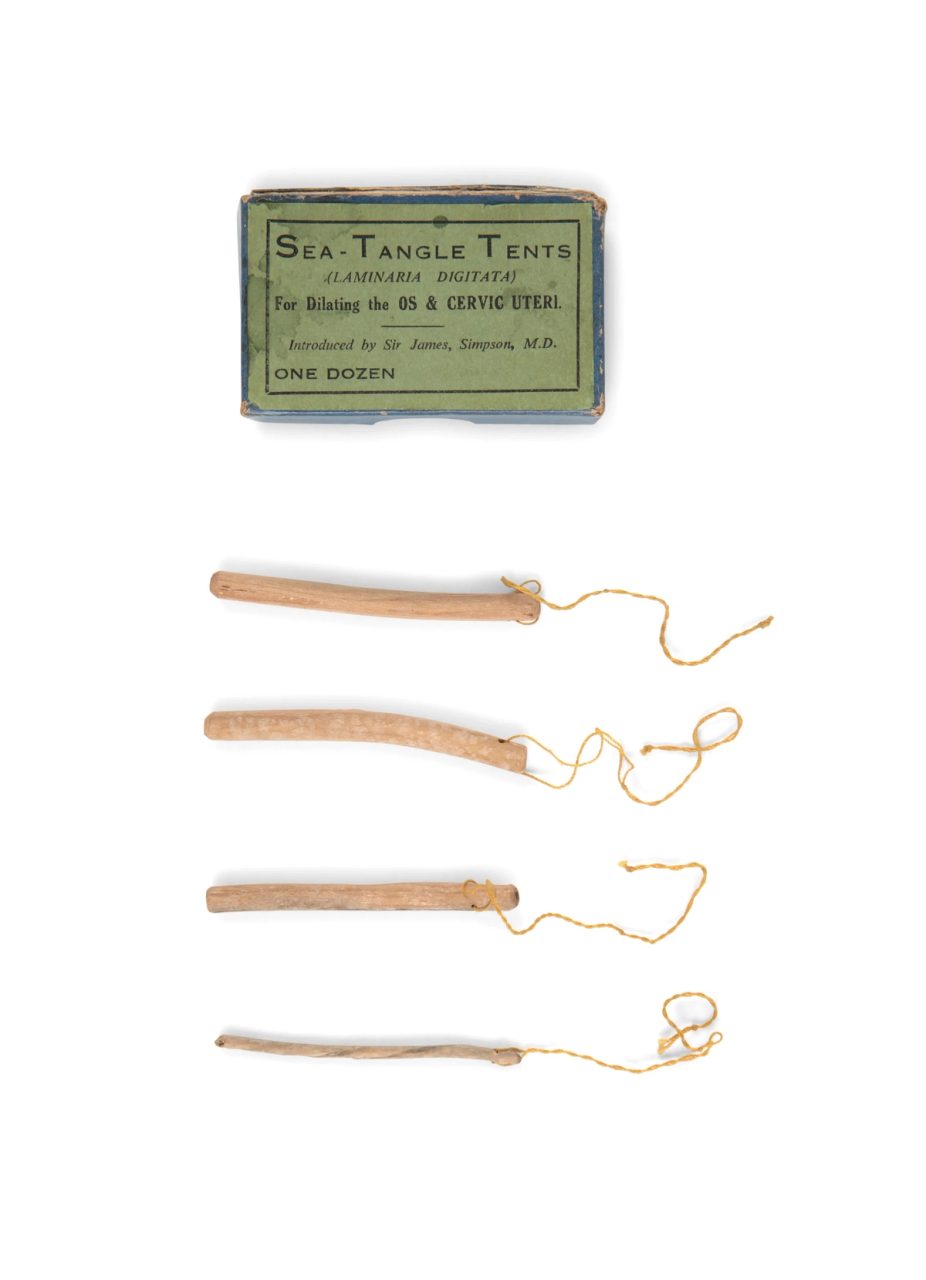

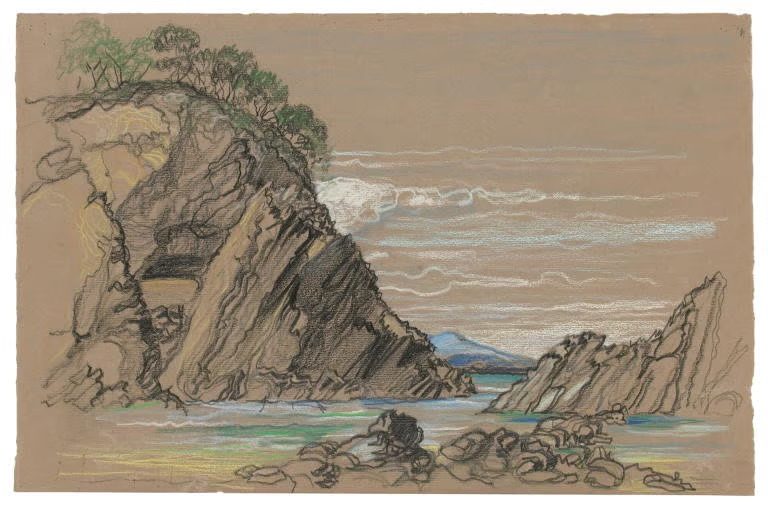

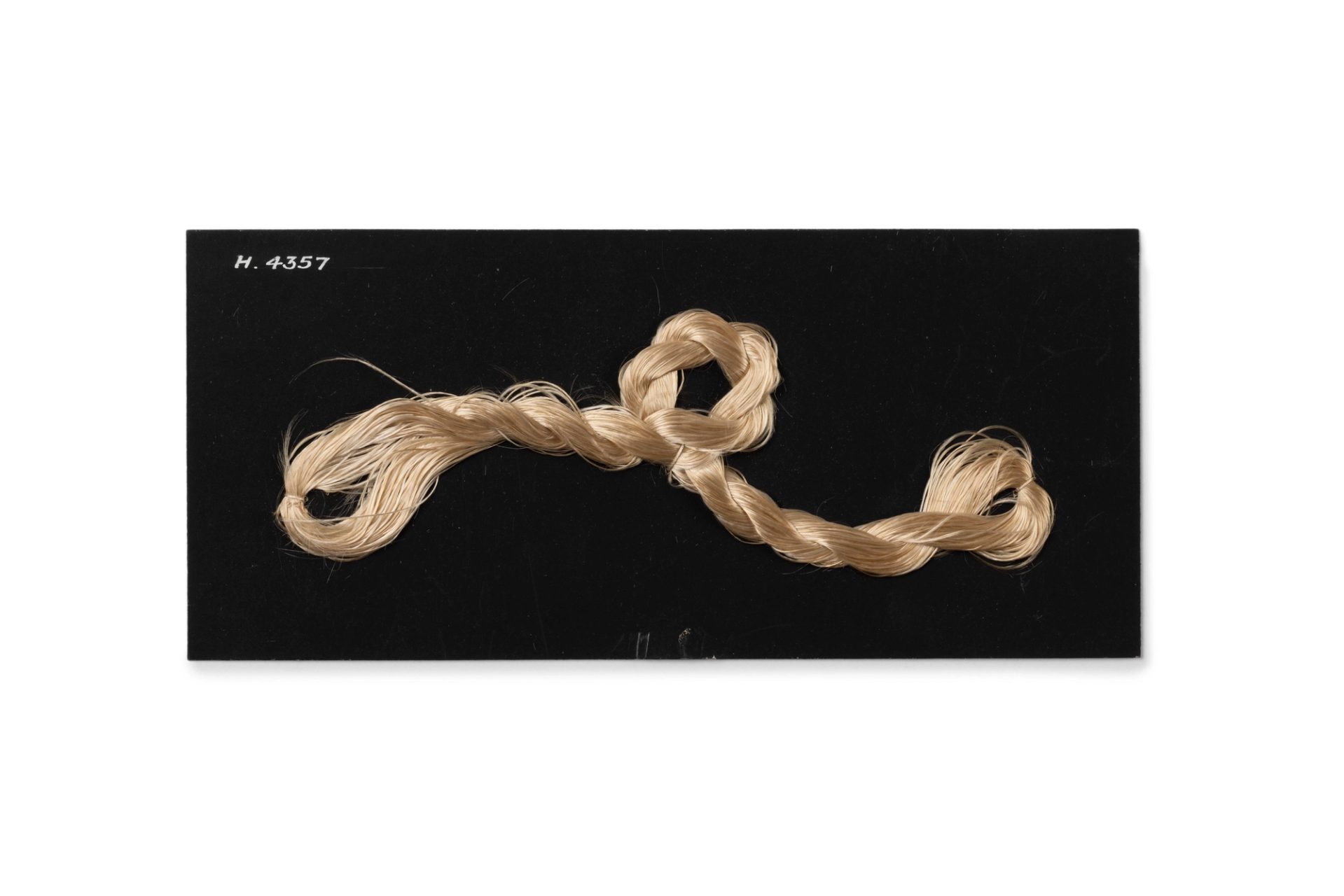

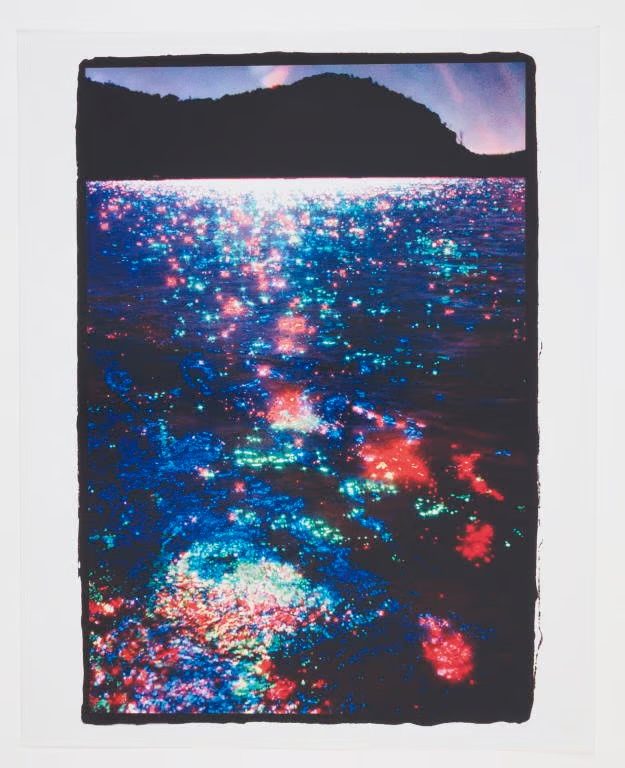

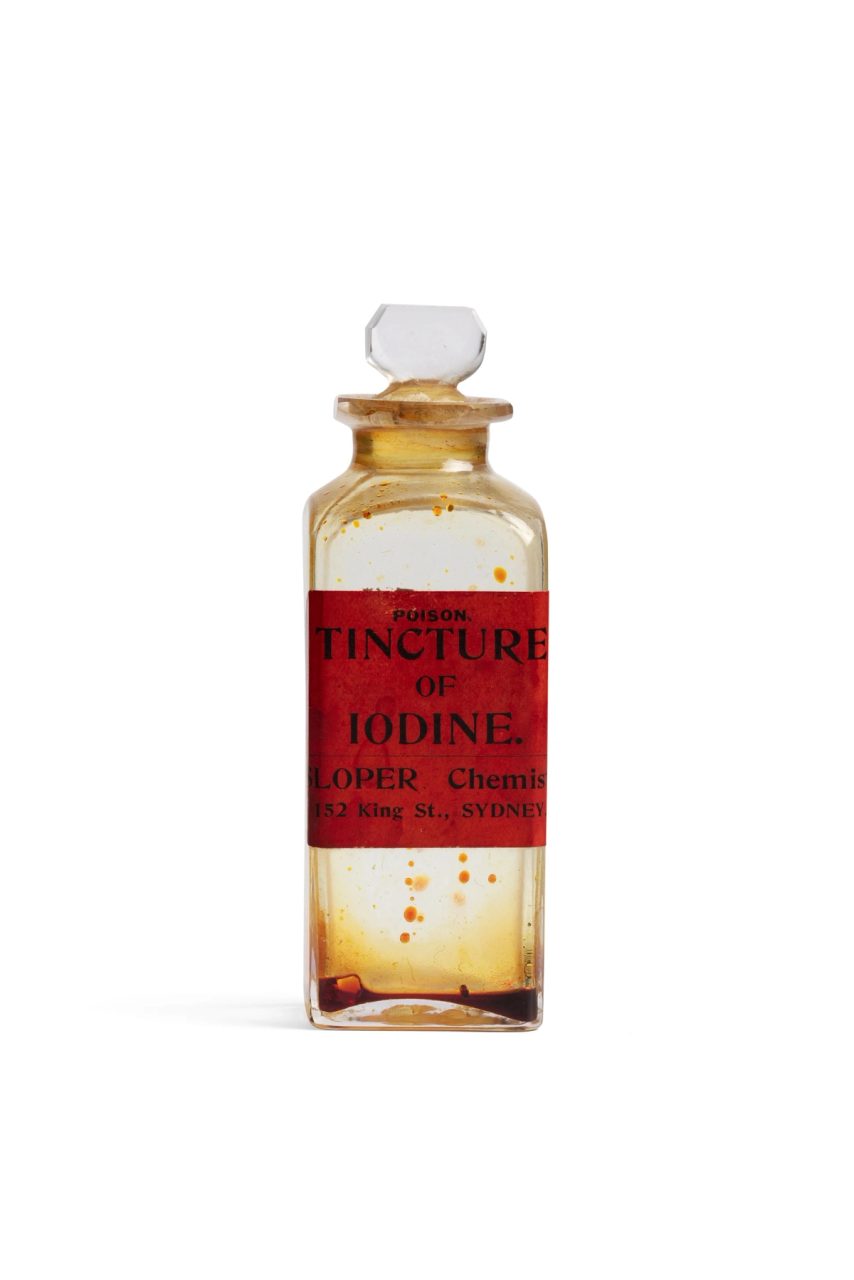

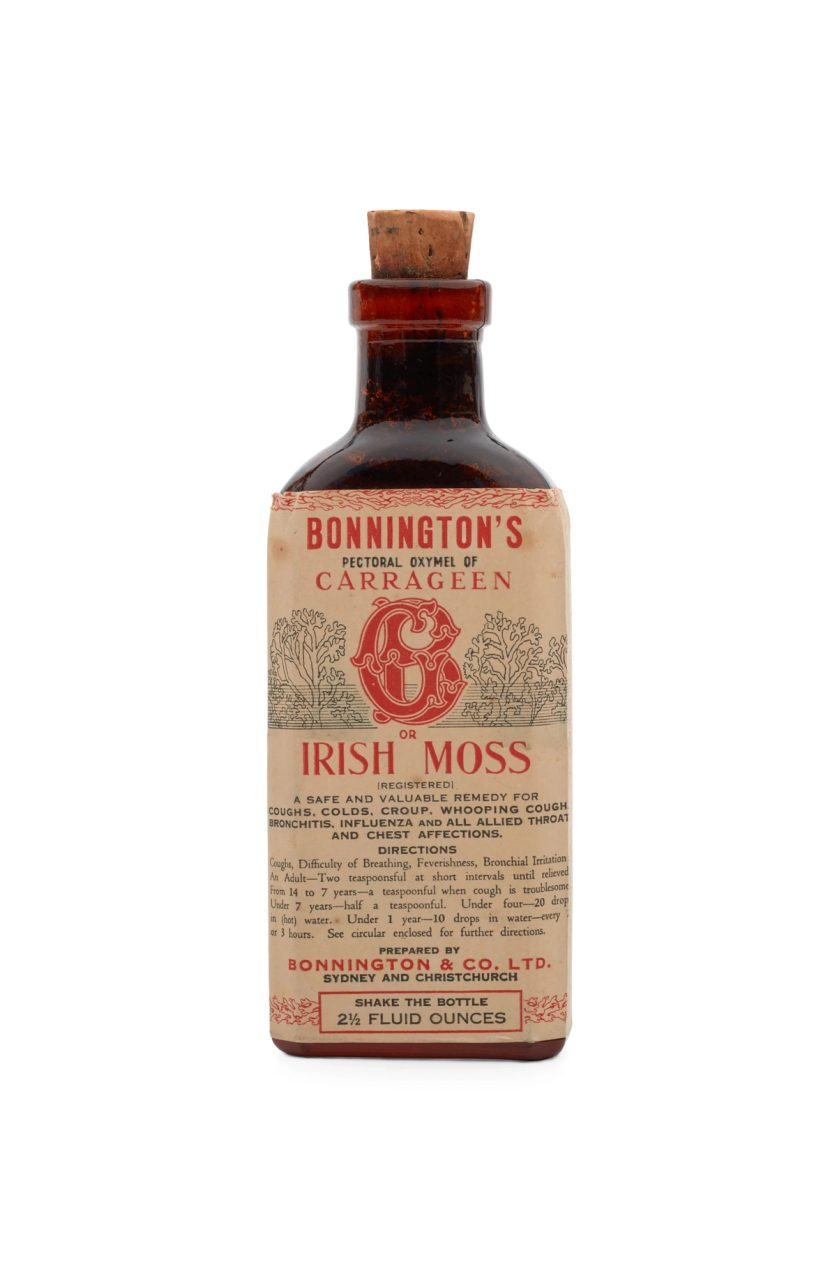

When you skip by seaweed on the beach or crunch into nori wrapped sushi rolls, you're interacting with something that also exists as billion year old fossils. In lutruwita/Tasmania, palawa people have crafted bull kelp water carriers for millennia, and from Ireland to Japan, seaweed’s been a culinary ingredient, a cough remedy and a way to pay taxes. Nowadays, this versatile alga gets shaped into sushi rolls, musical instruments, plastic alternatives, and could be a powerful tool in combating climate change.

‘Seaweed was used as a medicine. It was even used to pay your taxes. It's really an important cultural ingredient.’

Transcript

Lee Tran Lam Powerhouse acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which our museums are situated. We pay respects to Elders, past and present, and recognise their continuous connection to Country. This episode was recorded on Gadigal, Kaurna, Peramangk and Bundjalung Country.

My name is Lee Tran Lam and you're listening to season two of the Culinary Archive Podcast, a series from Powerhouse Museum.