LTL Native grains can have a significant environmental impact and it's clear we should embrace them.

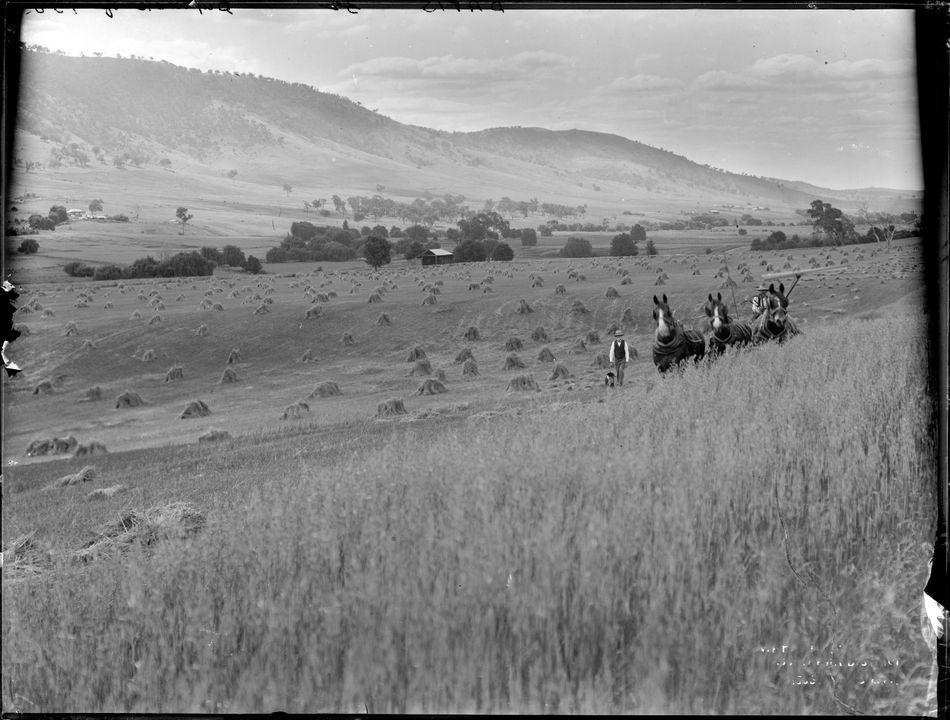

JB The time is really right to do it now, you know, with climate change being on a lot of people's agenda, food insecurity, rising costs of fertilisers, the rising cost of fuel, which is going to impact the cost of food. You know, nitrogen and fuel is a really big factor in our agricultural systems. It's really time to be looking at these long-lived perennial grasses that don't need fertiliser. They don't need pesticides. So, you're gonna save on fuel and you don't need to cultivate the earth every year to plant a crop and plant your seeds in the earth every year. So, you're saving on your fuel costs as well. And there's also a real hunger out there to start engaging with First Nations people a bit more meaningfully.

One of the species I can talk about is Mitchell grass, the astrebla species, that's my favourite. And I think that's – of all the grasses that we're looking at – that has the most potential. They live at least 40 years, possibly longer. So, they're the dominant grass from the more arid regions of Victoria all the way up through to Queensland to Northern territory and across to Western Australia. So, we have potentially millions of hectares of these grasses and because of habitat forming species, you're not going to have to try to maintain them in that paddock, for example. So, they're not gonna get outcompeted. They're also really, really significant culturally. So, there's this opportunity to start re-engaging First Nations people with culture and providing a culturally identified food product.

They’re really, really nutritious from environmental perspective. You're having these long-lived perennial grasses that can withstand drought. They're holding that soil together. So, you're preventing erosion 'cos they've got these quite interesting root systems that enables that drought resilience.

It's gonna help your water infiltrate into the soil a bit more as well. So, if your soil has more organic matter and more root systems holding the soil together, it is gonna be able to hold more water, which will mean the water's gonna run off into the rivers or into the waterways a lot slower. If we can get millions of hectares of this stuff, then it is gonna help, I believe in some way, mitigate some of your flooding that you get.

I'm really excited about, you know, the ecological environmental benefits that these grasses can provide. But I think what's motivating me more these days is the potential cultural impact and the social impact. We're almost talking about food sovereignty and self-determination.

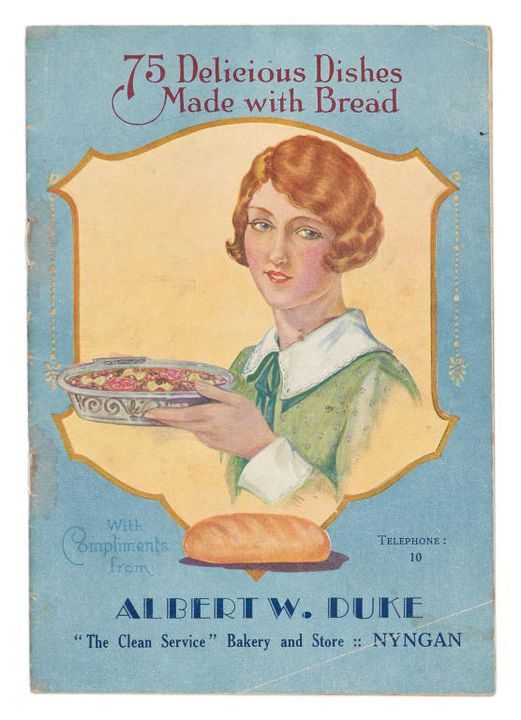

JO Where I come from, we've got kangaroo grass, we've got kurrajong seeds and we've got a lot of roots of trees. And so, the thing is in terms of grain, you know, for harvesting and for economic development, I think you'd have to just use whatever's there, whatever's on your Country. And if we go back and think about the traditional uses of making traditional breads from either nuts, grain or roots in different places, the diversity is so large. I remember when we grinded down some lomandra seeds for making bread, like the seeds out, this husk looks like a little popcorn seed. The little thing that come outta it was so tiny. So, you could imagine the amount of that you would need to make one bit of bread. I remember a project we did, and we ended up buying some kangaroo grass seed and it was like $500 for 500 grams. And you would have to just collect a lot to even be able to make a paste because these seeds are so small.

LTL You've just heard from Jody Orcher, a Ualarai Barkandji woman who was the Aboriginal education coordinator at Sydney's Royal Botanic Gardens. She also wrote the Bush Foods chapter in Australia: The Cookbook and appears in our ‘Oysters’ episode. As she points out, labour intensive production and hefty price tags are some of the roadblocks the native grains industry faces as it develops, but there are some ways to make it work.