The Holding Pen

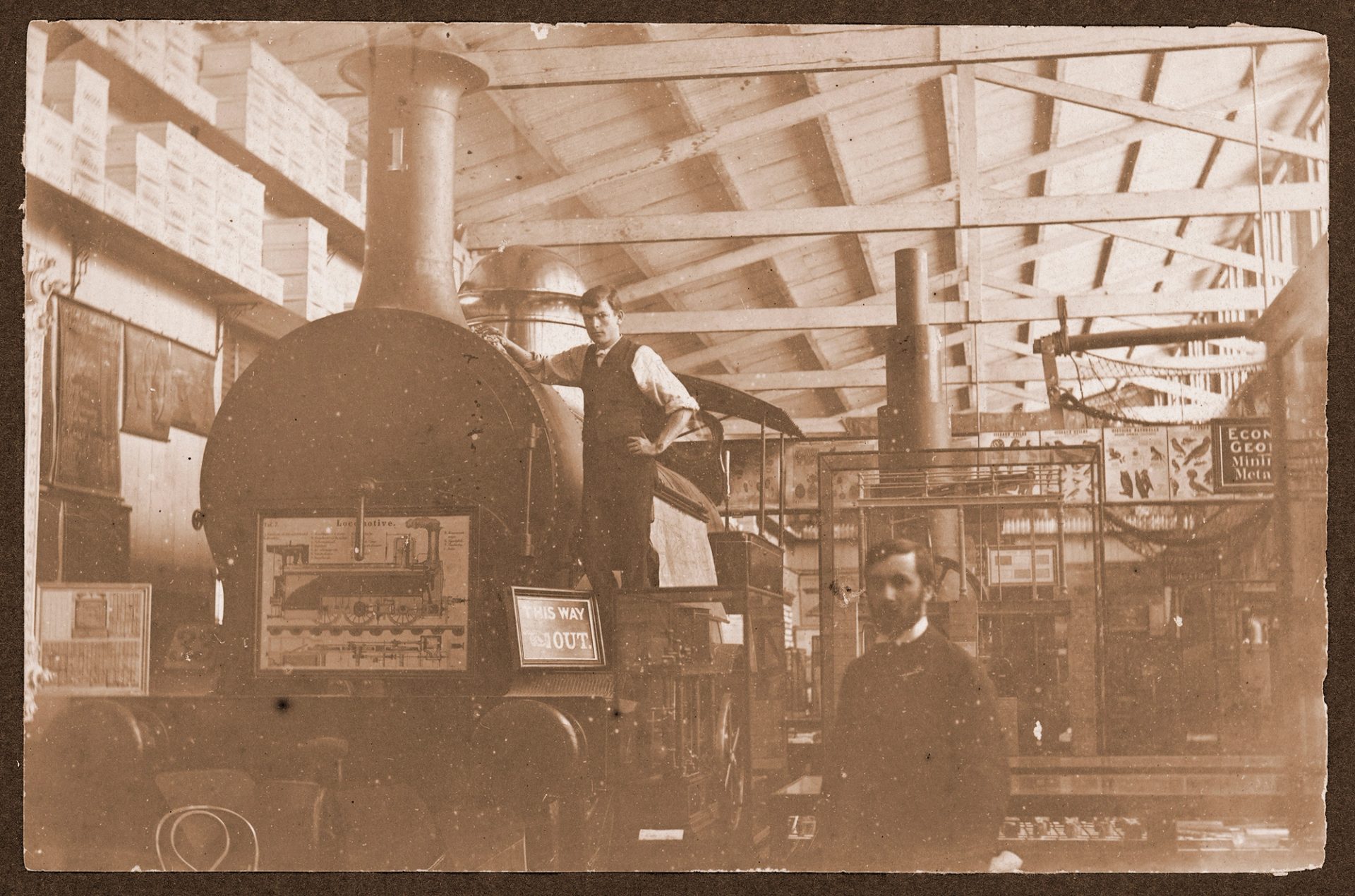

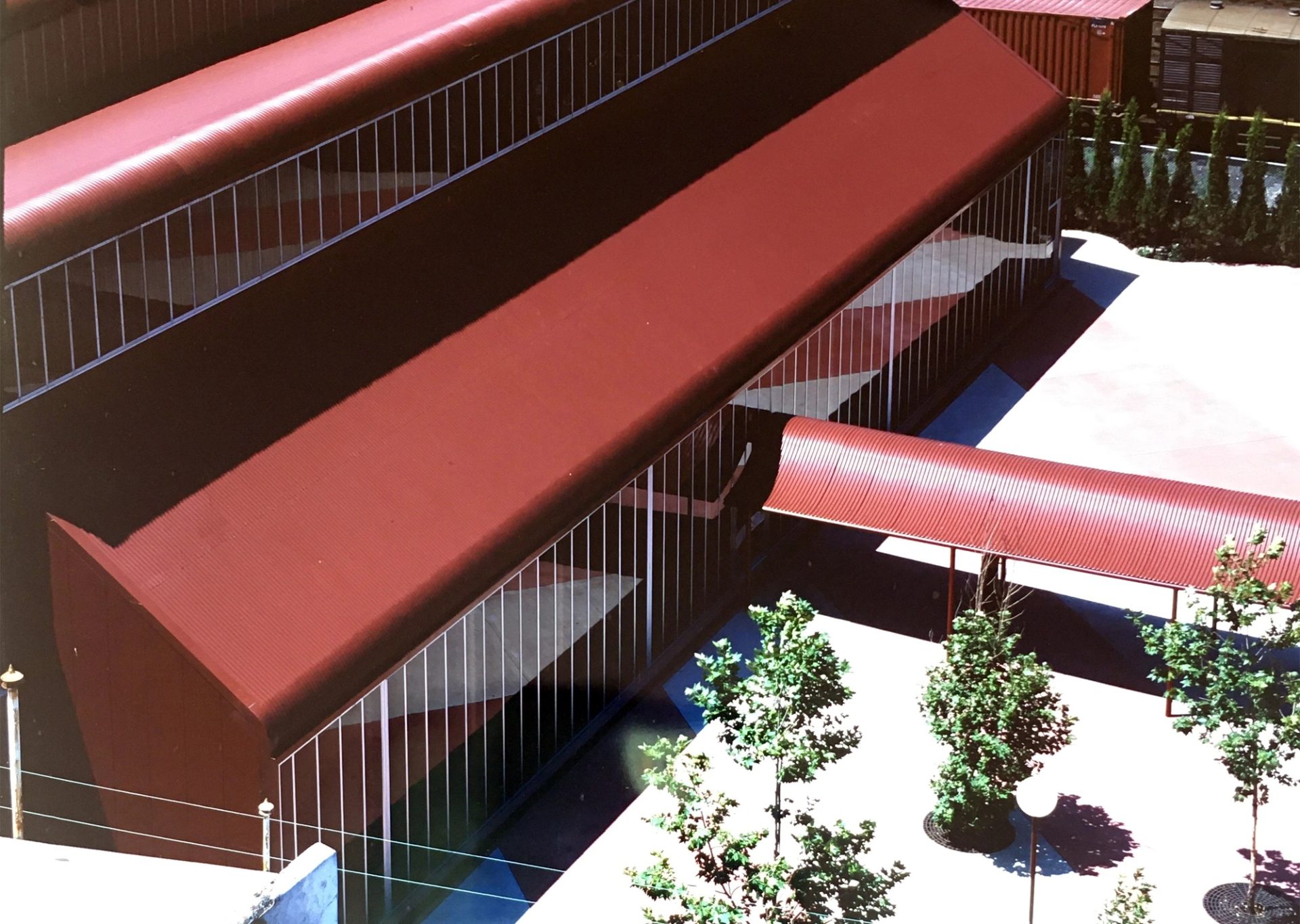

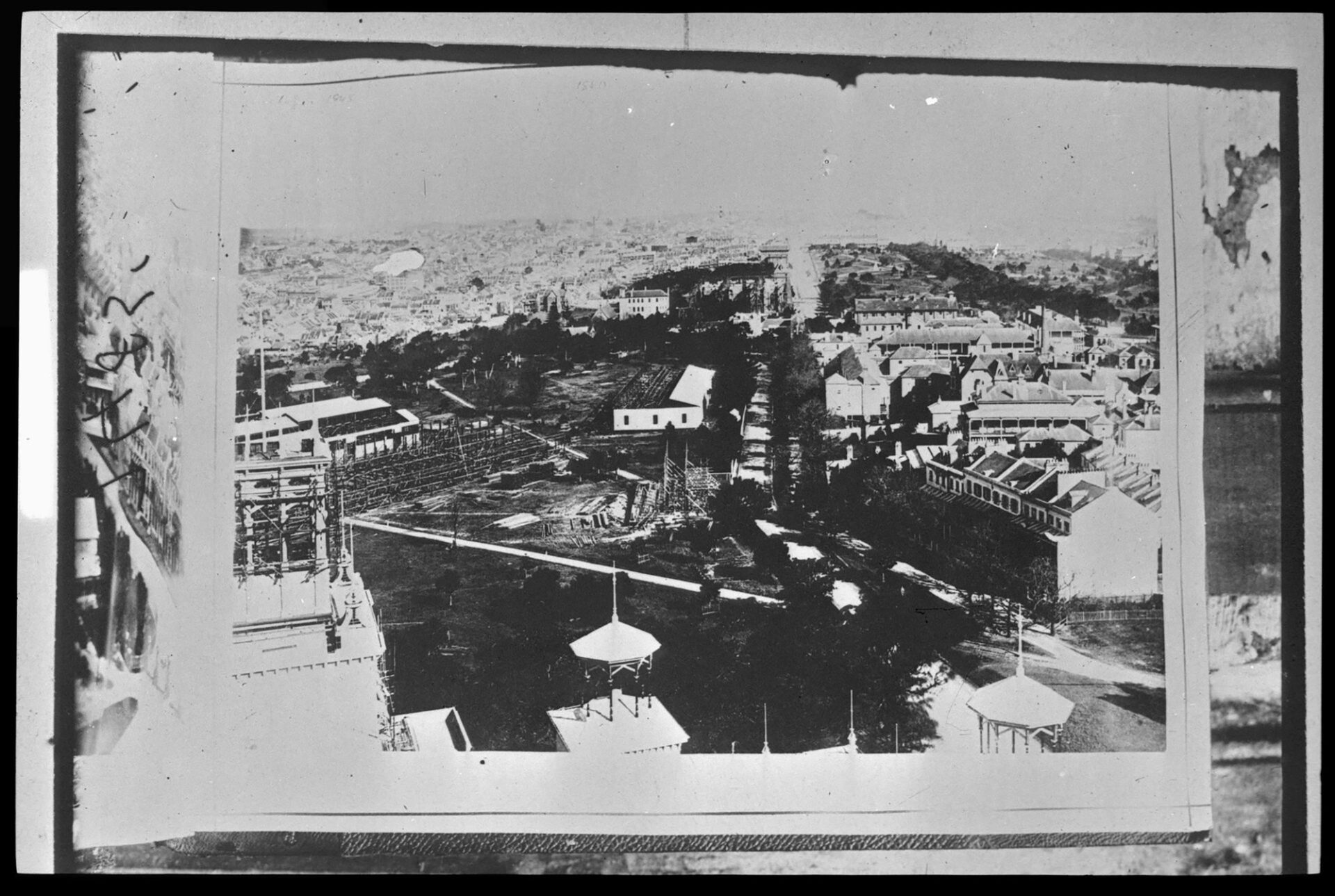

‘The Colonial Secretary has caused that portion of the Agricultural Hall which is not occupied by the authorities of the Sydney Infirmary to be handed over to the Committee for the purposes of the Technological Museum’

Beginning Again

After the 1882 fire, the museum’s first Curator, Joseph Henry Maiden, throws himself into securing accommodation for a new museum, and establishing a new collection.

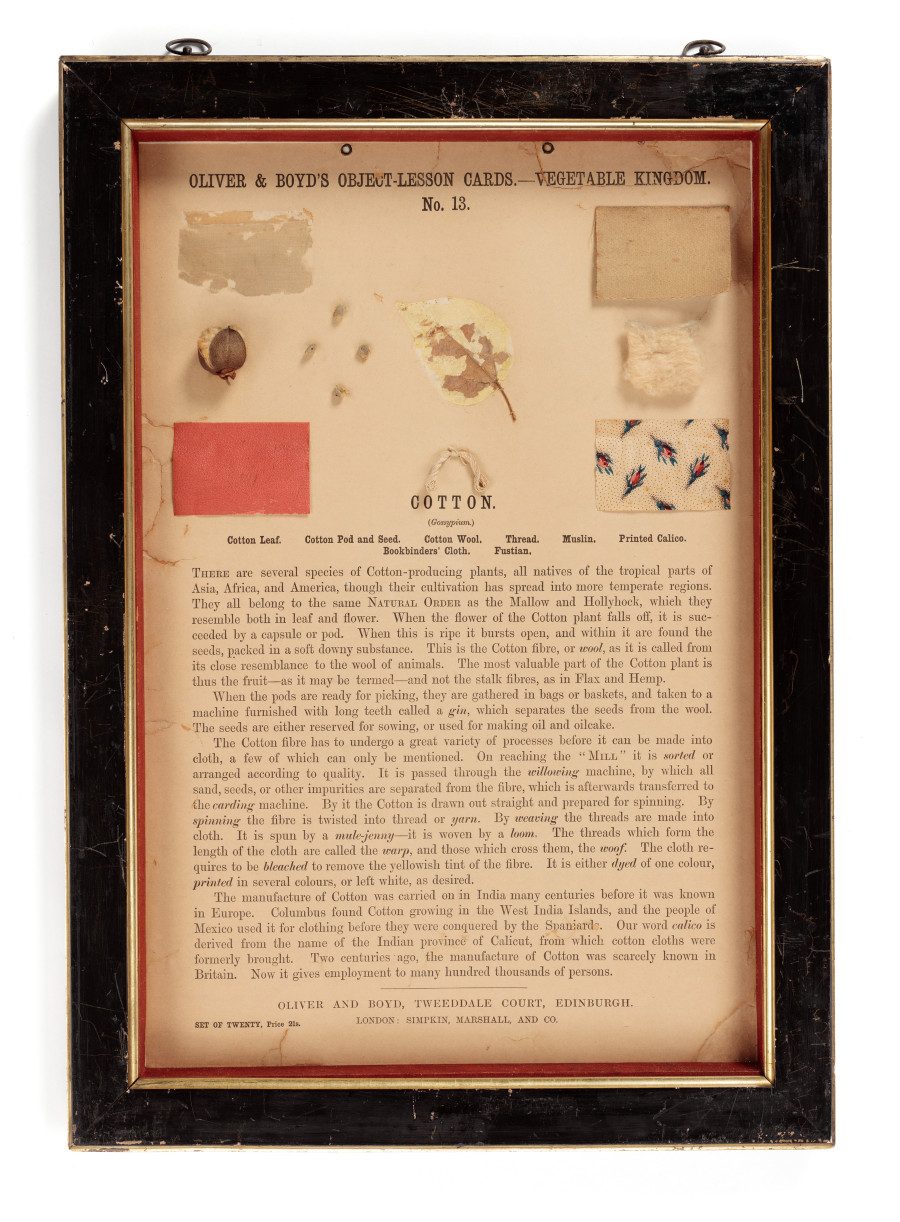

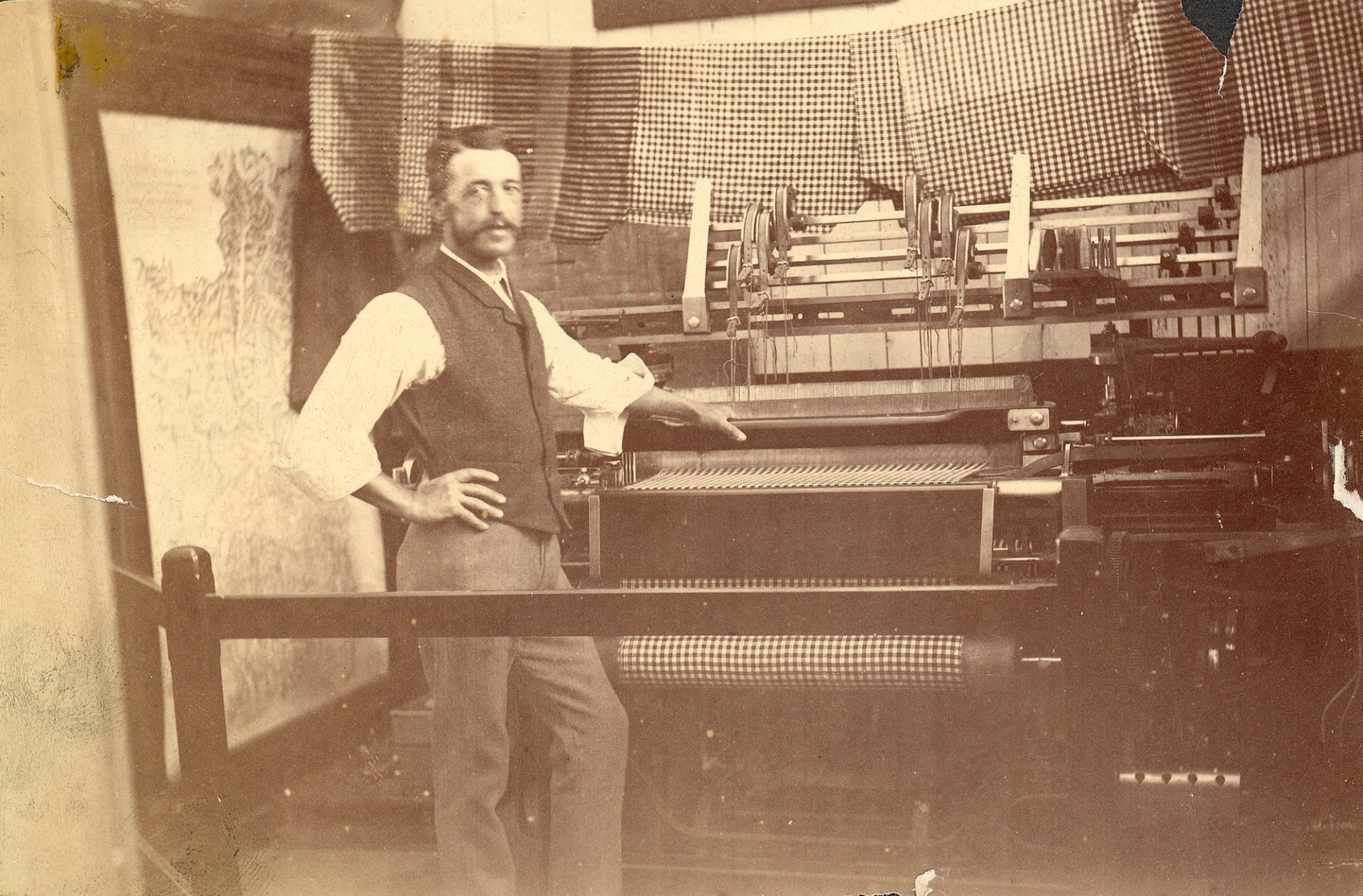

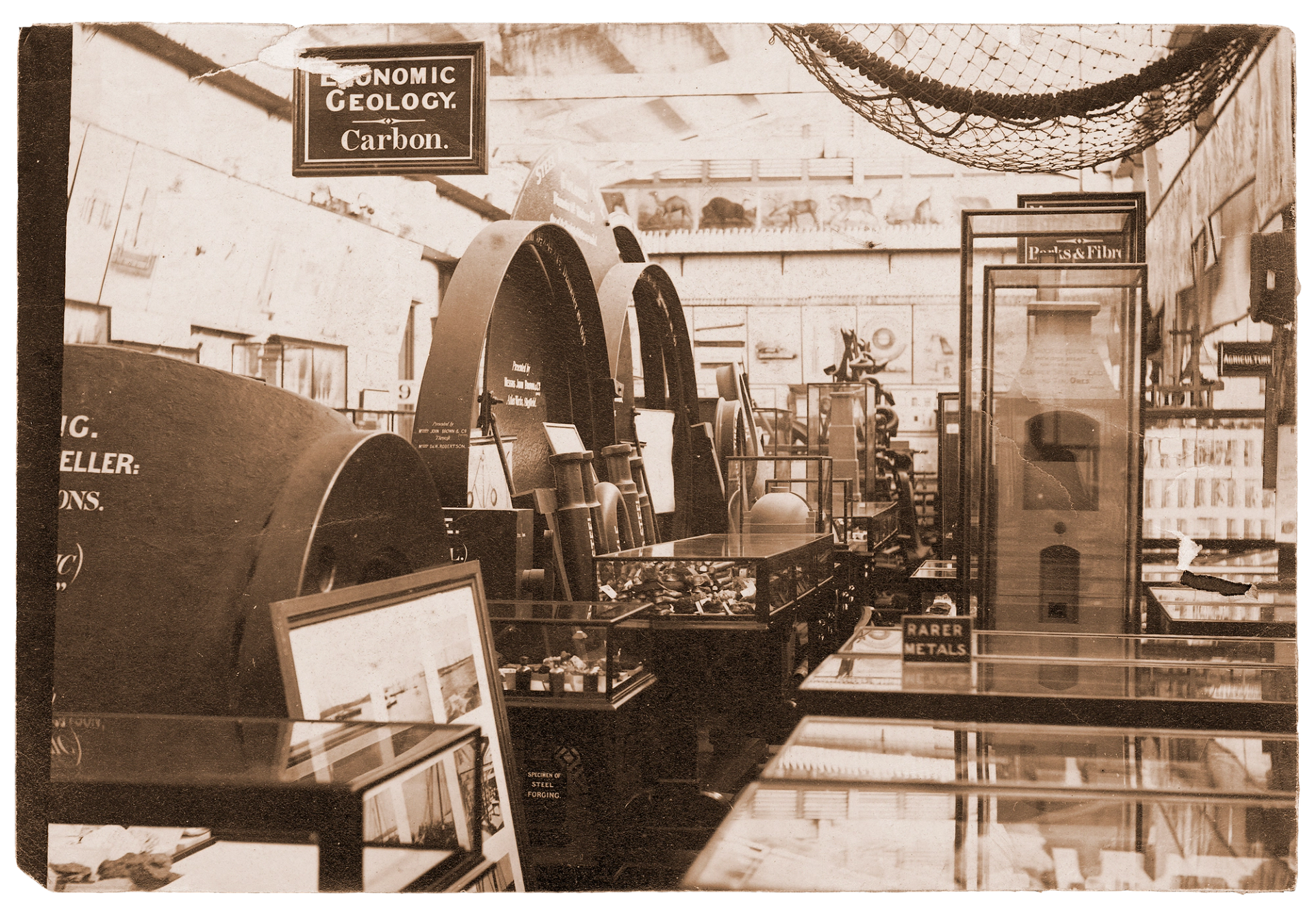

As Jack Lehane Willis reflects: ‘the Museum at the end of 1882 had virtually ceased to exist and Maiden perceived clearly that the collections which he would now have to go out and actively seek would have to be those which would serve the purpose of instructing people such as tradesmen, engineers, architects, who had no other source of such information to turn to in New South Wales. If, at the same time, attention could be drawn to the abundance of raw materials of all kinds available in the Colony and, by research into these materials, show how they could be utilised, then Maiden considered the Museum would be performing its proper function.’

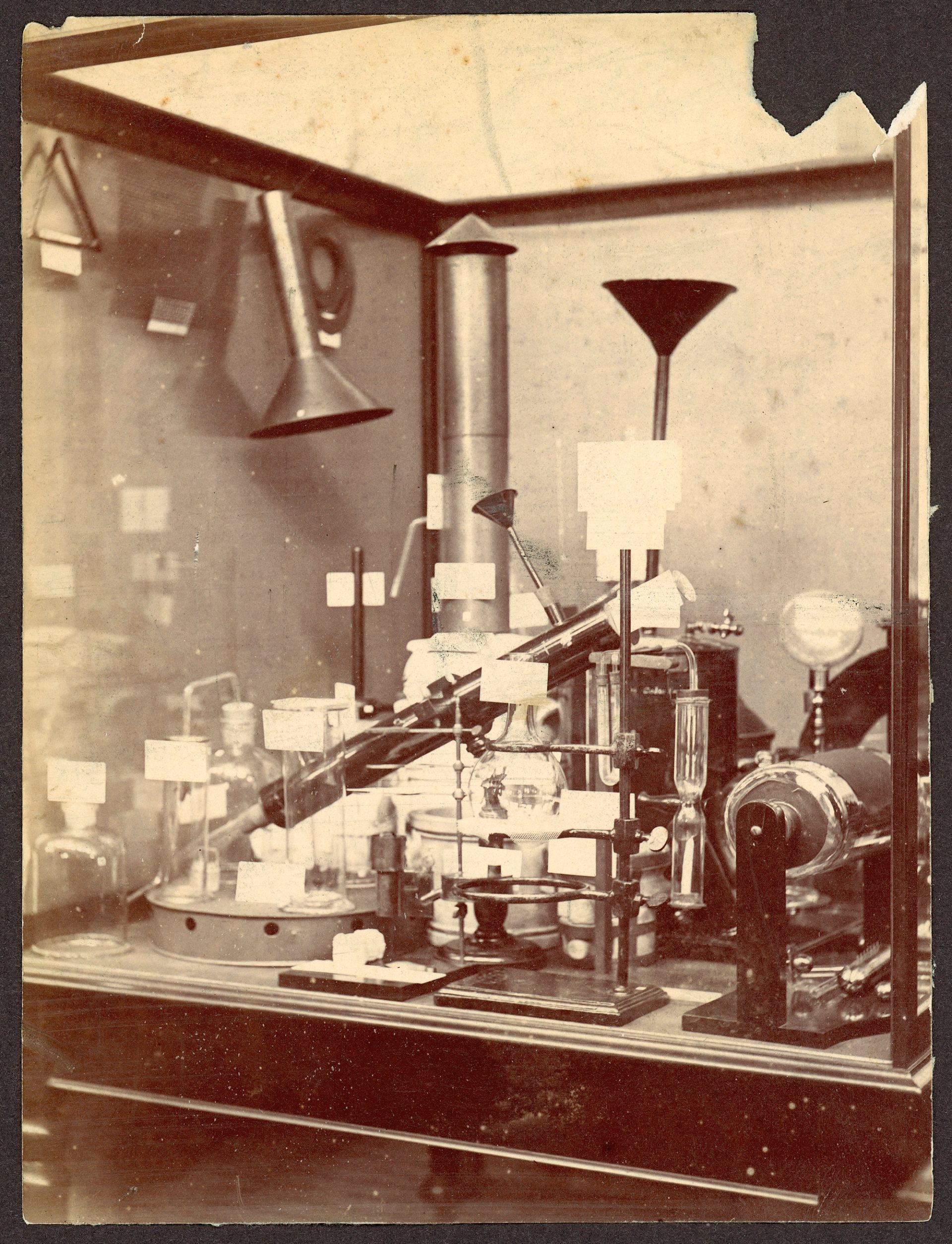

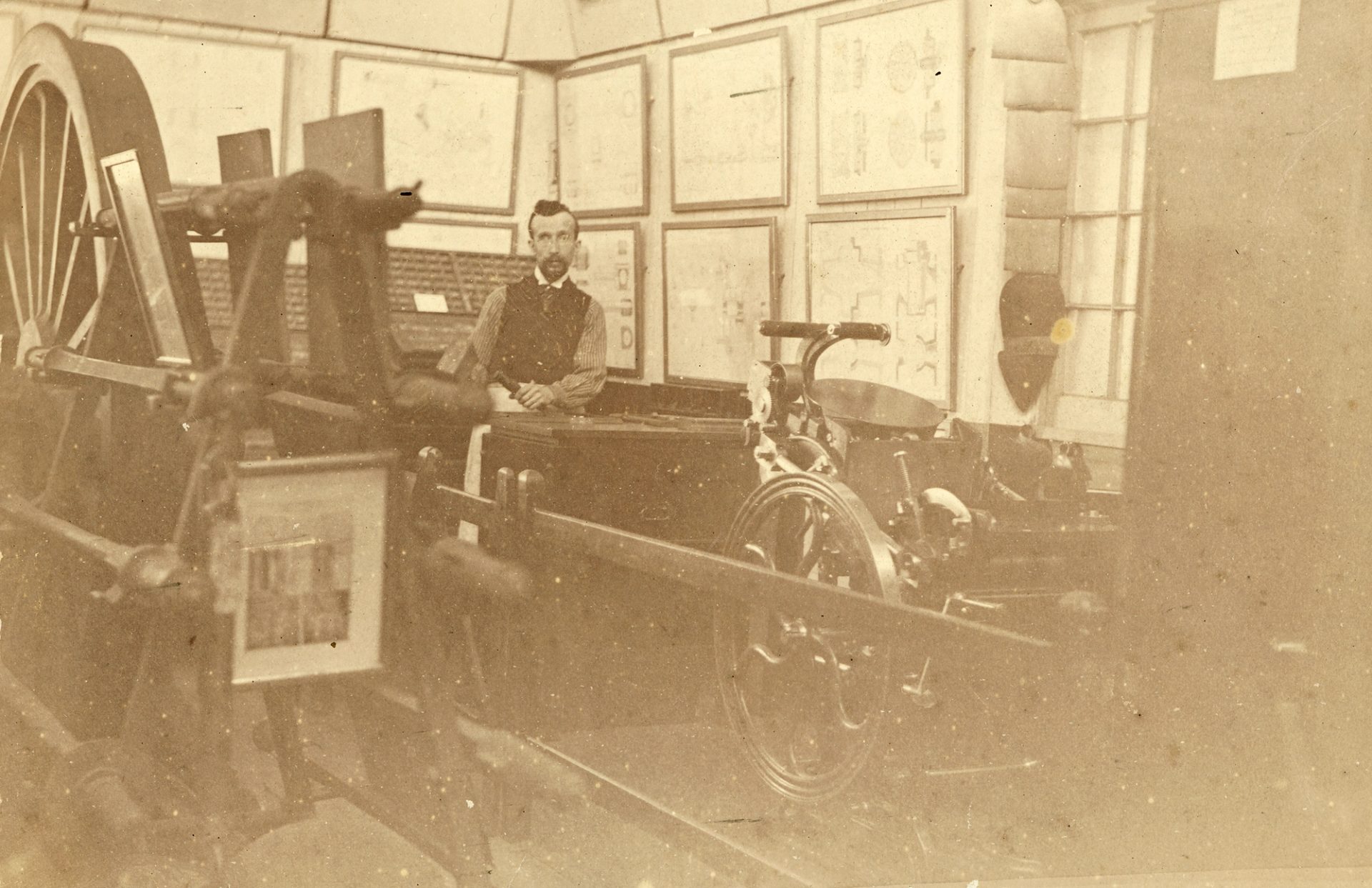

When the Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum opens to the public for the first time – on 15 December 1883 – it holds approximately 5,000 objects. The Agricultural Hall is a wooden, metal and glass structure built as temporary display space for latest agricultural equipment during the Sydney International Exhibition.