Transforming the Tramsheds

Civic Networks

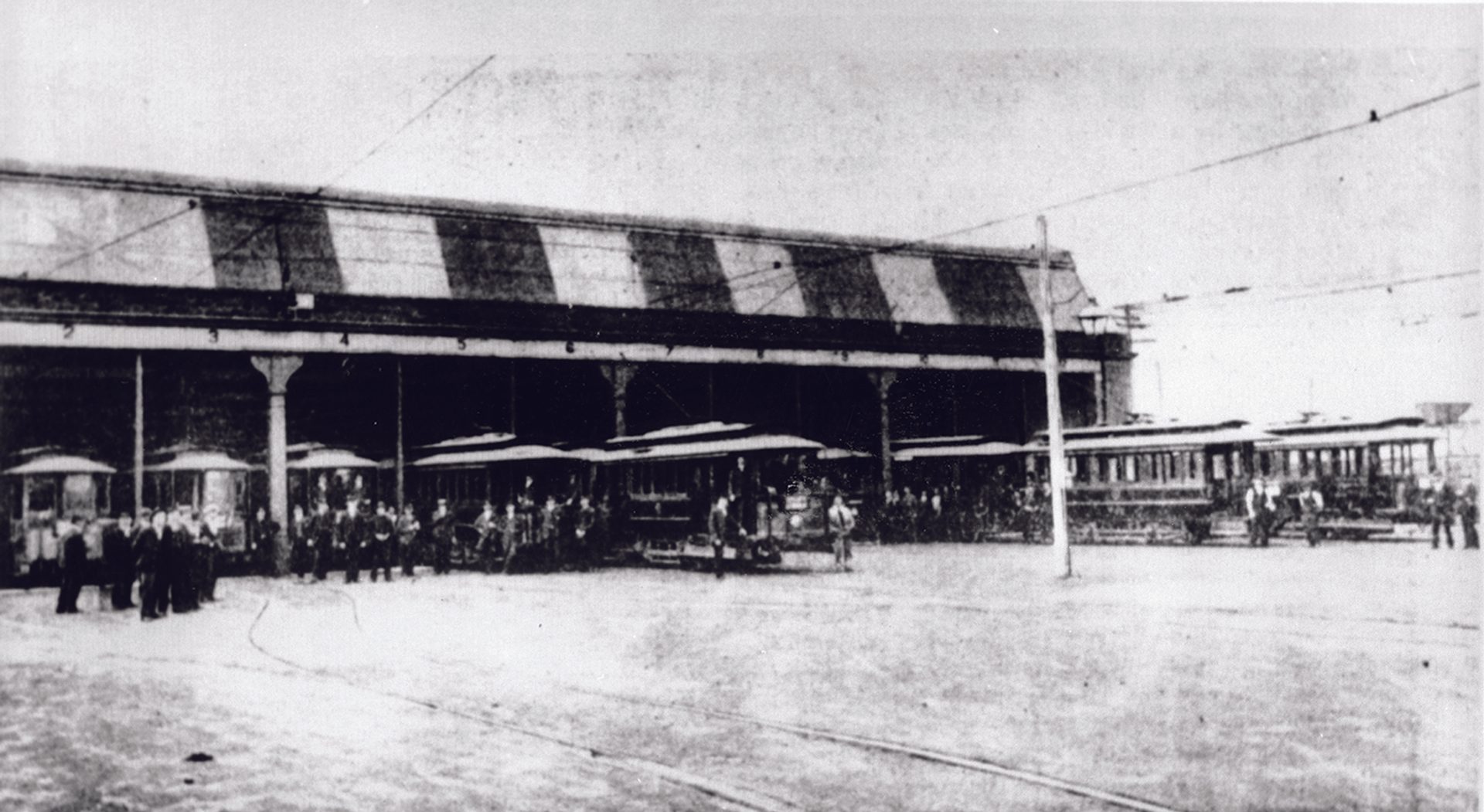

In 1879, a steam-powered tramway is installed to transport visitors to the Garden Palace and the Sydney International Exhibition. Four steam tram motors are imported from the Baldwin Engineering Company as a temporary transport measure for the Exhibition, and Baldwin’s travelling engineer, Edward Loughry, arrives two weeks before the Exhibition opens to get them into service.

The tram motors pull double-decker passenger cars along rails built by the Eskbank Iron Company in Lithgow – just four years after iron is first smelted there. The rails are laid on red-gum planks. This is Sydney’s first form of motorised public land transport.

‘We learn that the Works Department is making arrangements for construction of a temporary tramway from the Redfern terminus, along Elizabeth-street to Hunter-street, to be used by visitors to the International Exhibition. They expect to be able to get motors from America, and it is probable that the rails and other material can be obtained in the colony’

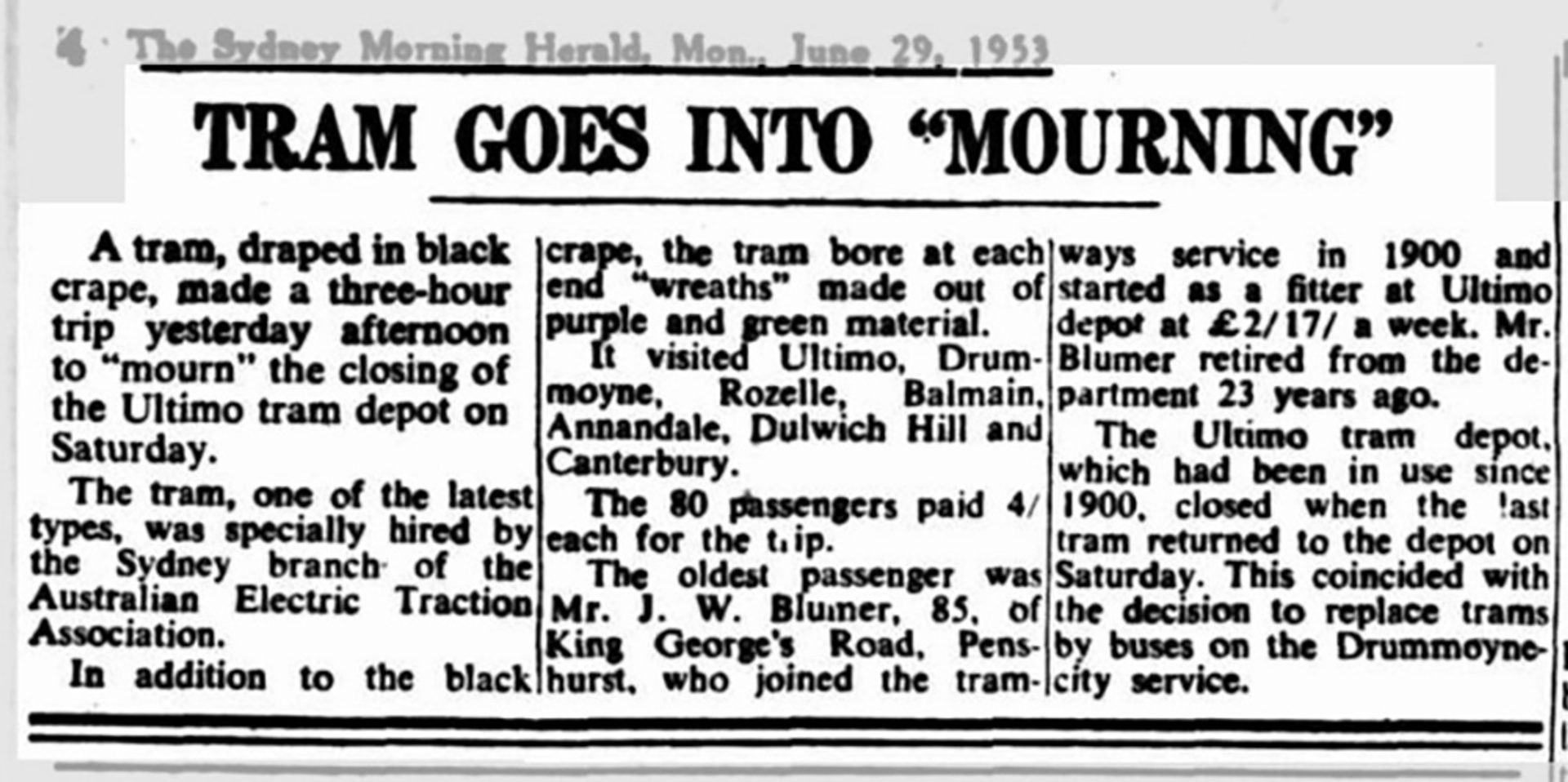

The trams are a highlight of the exhibition and are retained when it closes in 1880. This forms the basis of Sydney’s first tram network. The first extension, to Randwick, is operating later that year, and the network reaches its peak in 1894 with more than sixty kilometres of track and over a hundred steam trams in service.

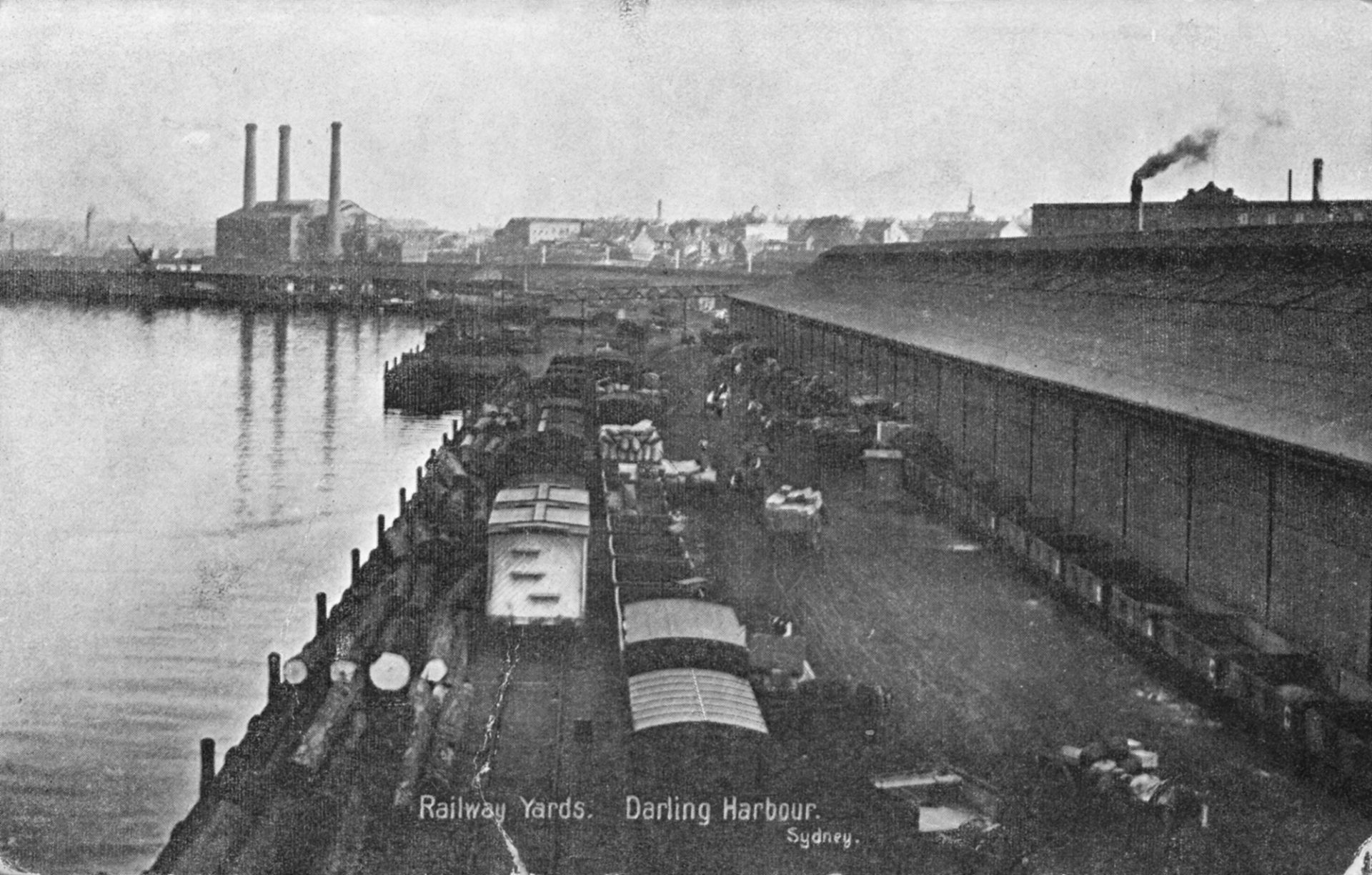

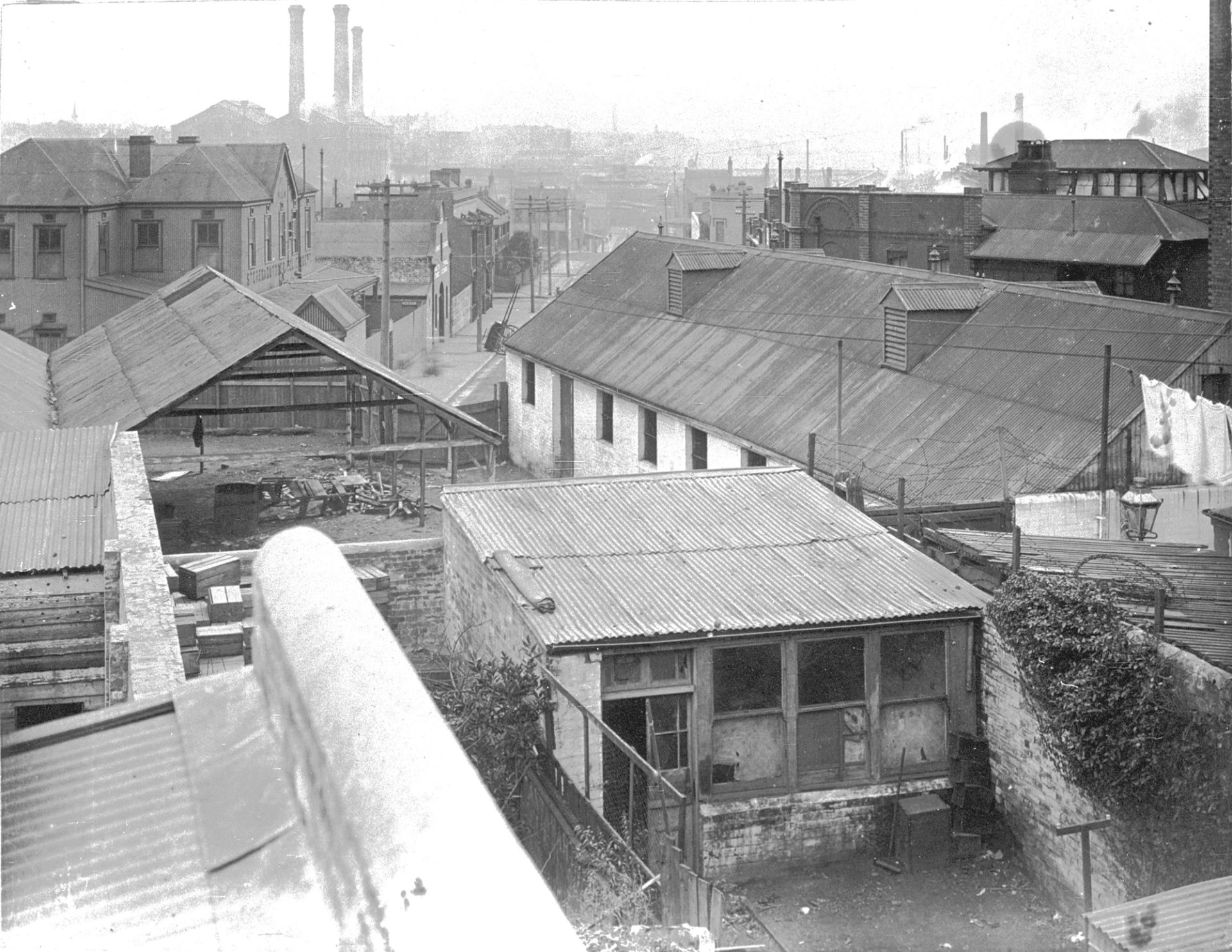

In 1905–1906, the tramways are converted from steam to electric. Ultimo's Power House – built ‘in the Italian Renaissance style of architecture’ – is the first electricity station built to service this public transport.