Tom Fereday

‘I realised a long time ago that what works for me is collaboration: when I can find the right people to work with, we can push off each other to make a greater result than perhaps we could have done individually.’

Tom Fereday’s fascination with the tension between natural materials, design and manufacture developed early – his Dad was an antiques dealer in London – and he remembers fleeting moments with ‘everything from Victorian to Turkish wooden artifacts to 60s and 70s Scandinavian pieces’ while growing up in a ‘rotating house of objects’.

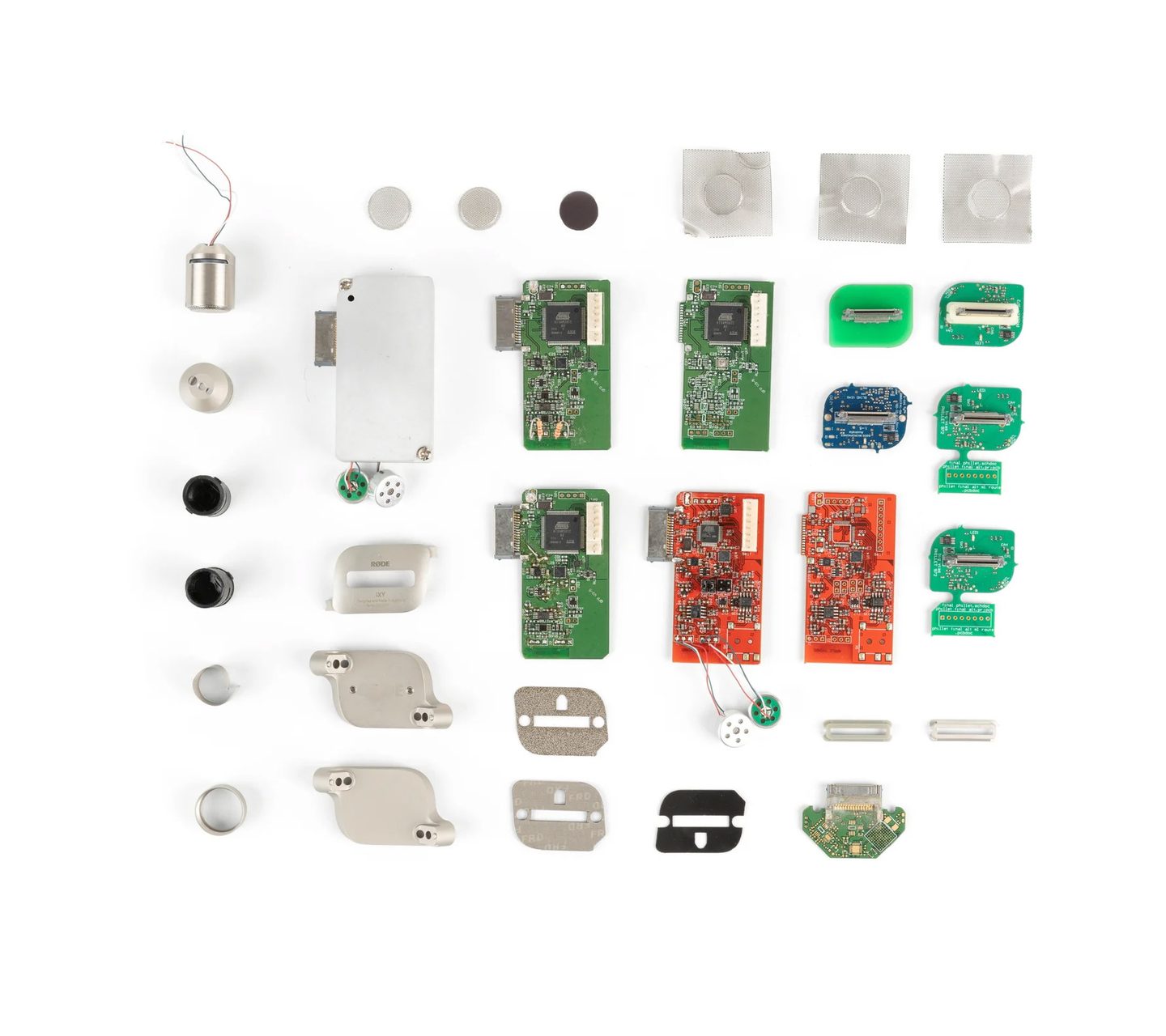

Though he initially studied Sculpture and Graphic Design at Wimbledon School of Art, he found the freedom of creating his own narrative 'overwhelming'. Fereday returned to Sydney (his birthplace) and enrolled in Industrial Design at the University of Technology Sydney, where he thrived under the constraints and problem solving inherent in object design – gaining first class honours. His early career spanned Europe and Australia, including stints with Marc Newson Limited in London and RØDE Microphones in Sydney before establishing his own practice, Tom Fereday Design, in 2012.

Collaborations with brands such as Louis Vuitton, Alessi and Stellarworks have been presented internationally, and his works have been exhibited at Powerhouse Museum, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and The Australian Design Centre.

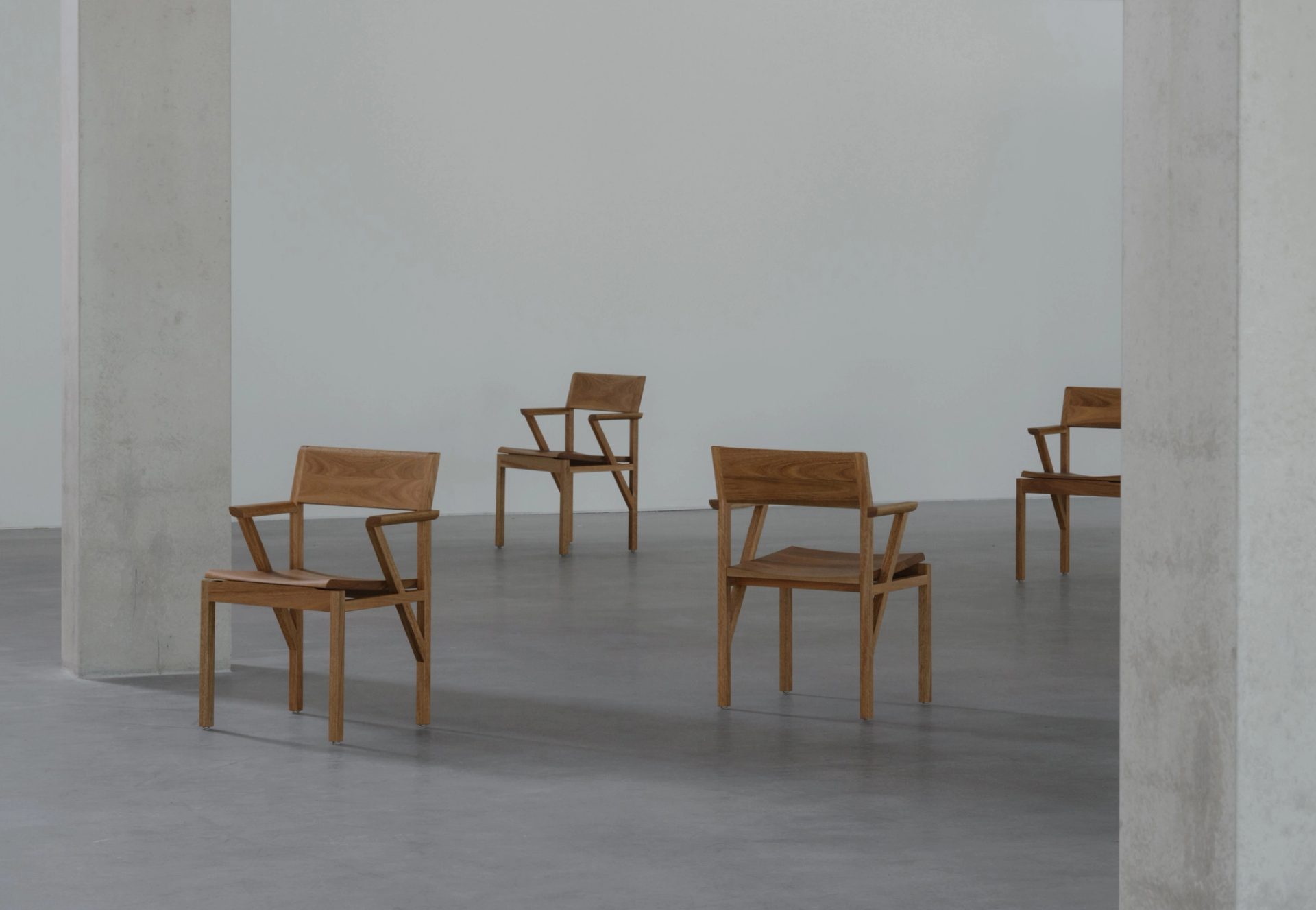

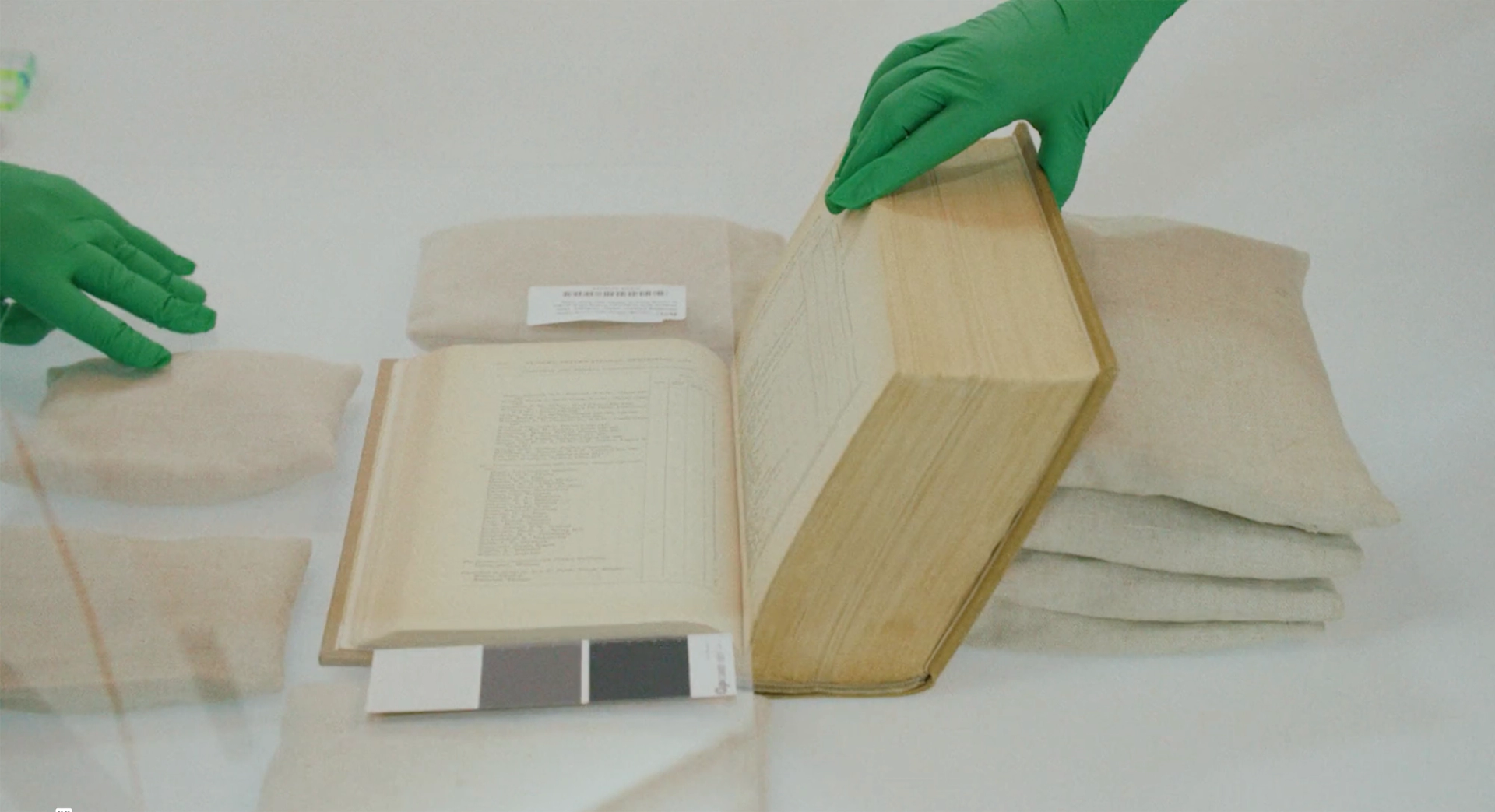

In 2023, design consultant Emma Elizabeth worked with Powerhouse to commission Fereday to design a large spotted gum ottoman for the entrance to the new Building J at Castle Hill. He developed it in collaboration with Evostyle, a local master woodworking business based in South Windsor. He then gained two more commissions: a series of cast aluminium cafe chairs and four spotted gum Sibling Chairs as part of a meeting room collection featuring eight Australian designers.

Stuart Ridley spoke with Fereday about his design values, collaborating with artisans and the importance of cultural institutions to the design world.