A Magical Process

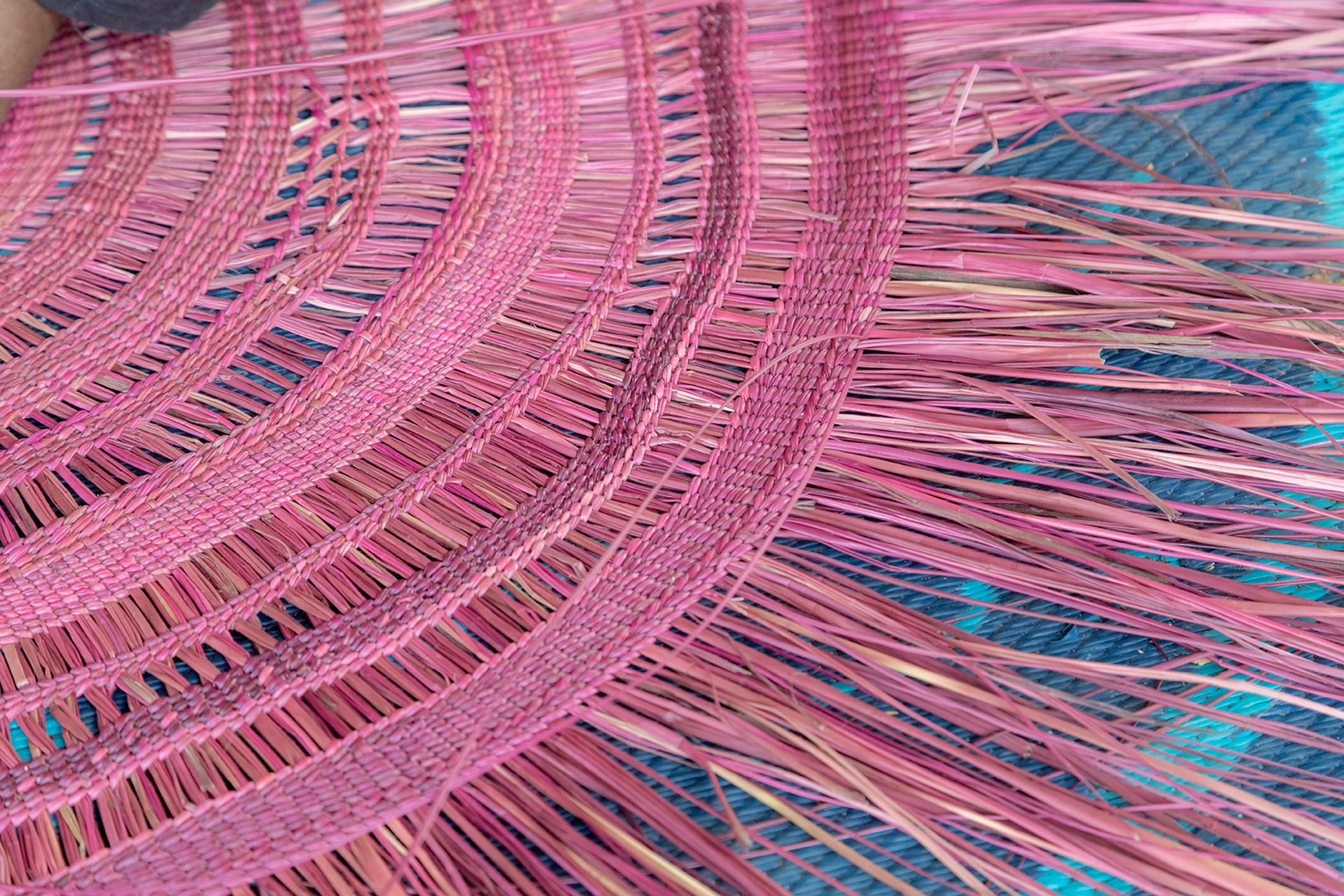

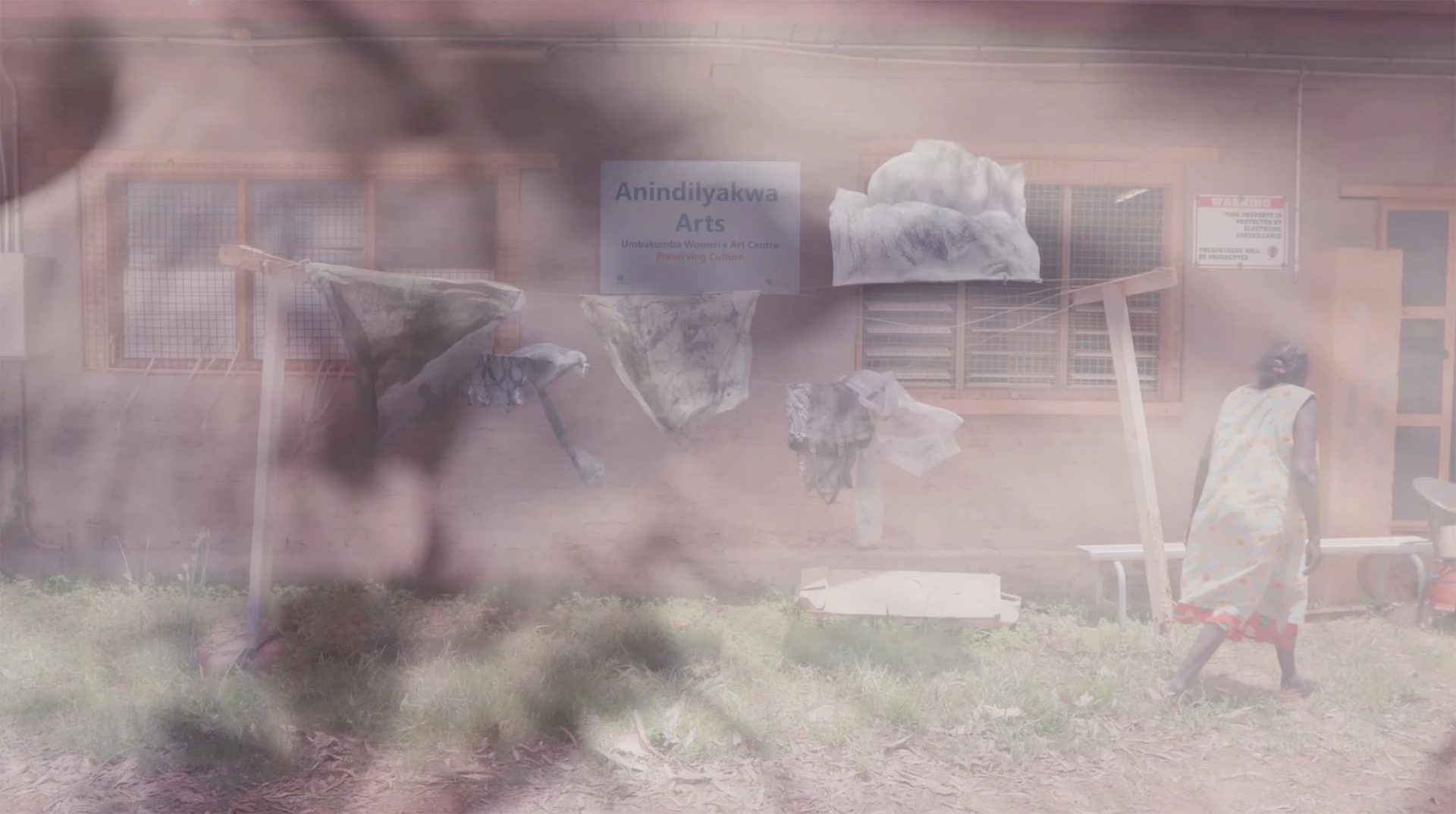

Light, layers and tactility – Alchemy is an exhibition that displays new commissions by First Nations creative practitioners from across Australia, particularly the Northern Territory, who specialise in natural dyeing techniques. Taking its title from the protoscientific tradition of transforming one kind of material into another, Alchemy uncovers the mysterious processes involved in producing pigments and dyes.

Extending beyond process, this exhibition also shares the wider social and cultural narratives that surround each of the commissions, such as the matrilineal relationships embedded within industry practice.

Inspiration

The concept for Alchemy is not mine. It is an extension of the Powerhouse Museum story loosely mapped out by the inaugural First Nations Director, Emily McDaniel, who was also on the curatorium for the museum’s 2022 exhibition and publication Eucalyptusdom. This is the story of institutions, a rolling continuum of bodies and minds that come through the doors over the years. We add sentences to the narrative. I picked up this half-sentence with the task to complete it. The next cultural custodian will do the same. Find the sentences I didn’t finish and complete them. So it goes.