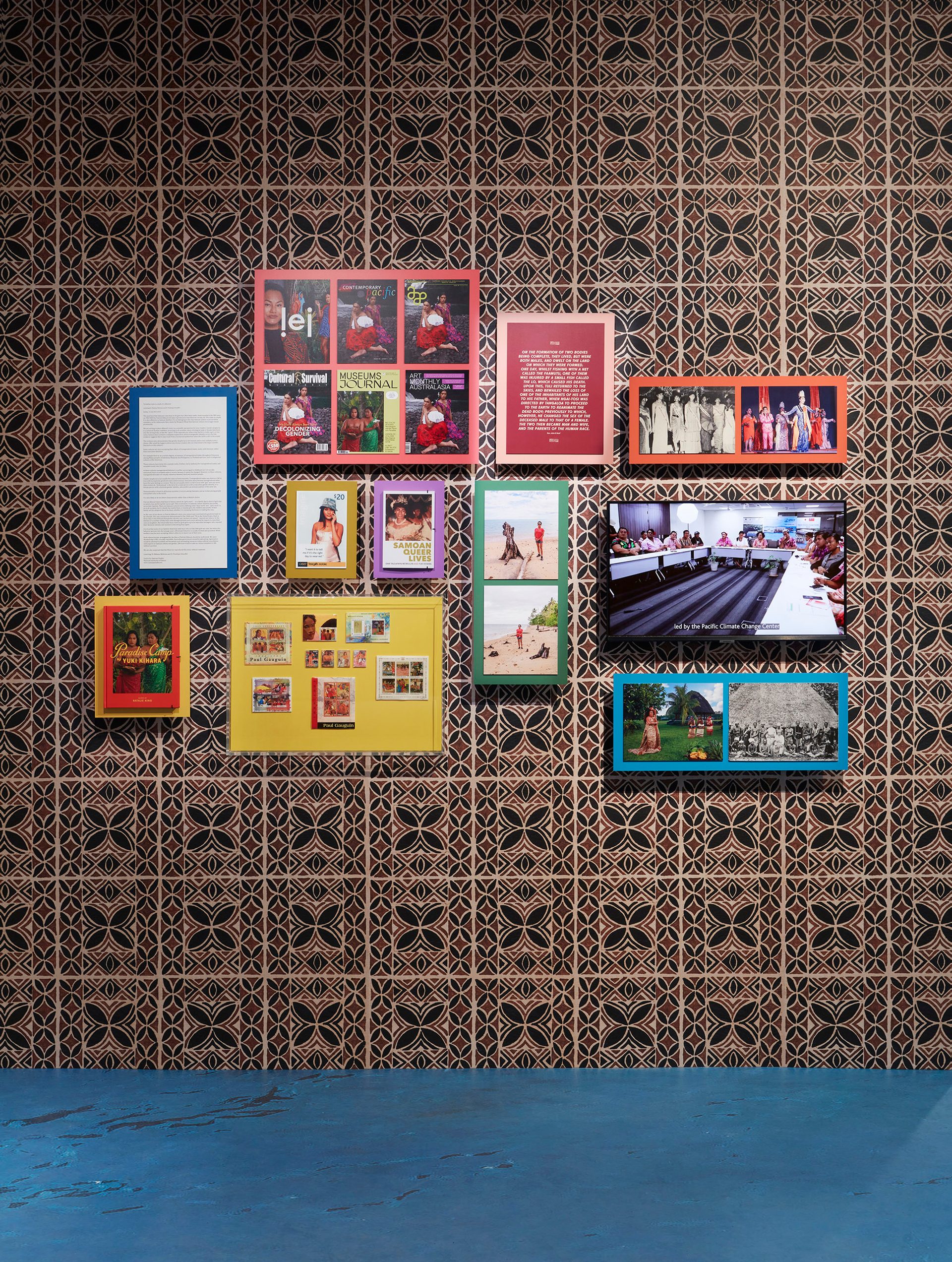

Aboriginal people – all people, really – speak to me through the way that they hold themselves, their gestures, their postures, the gaze. How the lips sit on their teeth. The energetic flow even through stillness. So even when I'm not intimately associated with a culture that's been captured on these glass plate negatives, there's many physical idiosyncrasies, eyelines and gazes that are consistent across time and geography and culture. The human traits of universal experience, in which offer all of us many clues for illuminating the real, full picture beyond the picture. So, you can imagine when Yuki Kihara came along to share her extraordinary revelations about the photography of her homelands and community in Sāmoa, I was just a little bit obsessed, especially with her discoveries about Gauguin. Being a performing artist myself, who works primarily with the body and movement, I was especially provoked by the potent physicality that commanded Paradise Camp overall, and the joyous, celebratory style of Yuki's photography. What glorious ownership on display!

Gauguin’s bodies in action in the Vārchive component are expressive but in more subtle ways. And I wonder if this is because he offers his subjects through like a double filter. Kind of like a second sight, as his paintings are very clearly based on the photography of Thomas Andrew. It was these observations that really drove my own deep dive into the Vārchive, as a space where all possible potentialities exist together. The vā, like the dreaming, the space between the physical and the metaphysical. That wondrous place where memory and prophecy combine. But all that was, is and will be, are one. From a dance point of view, this is choreography. The building blocks of any choreography. Your body, your space, the energy you exert and then how that creates a sense of time. And this is the Vārchive through and through. As dancers, I've remarked before that our realm of storytelling lies between the lines of narrative, and I think this is why works such as Paradise Camp and the Vārchive is so important to archival interrogation, because it is what lies between these, where the story lies, particularly for a performing body whose responsibility is to show you. I can't tell you, I can only show you.

One of my most influential dance teachers, Dr Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, once said to me, ‘Tammi, the body speaks. It does not lie. The more you try and tell a lie with your body, the more it is going to tell the truth on you.’ Elizabeth was warning me about embellishment. And so, Kihara's models, in stark opposition to Gauguin, are empowered. They're holding firm in truth, and Yuki doesn't attempt to deceive her audience about who or where these subjects are. They're not othered or silenced, as Lauren Booker would describe. Instead, they're recognised and claimed and given voices to speak beyond the pigment and pixel in the most luscious, elaborate and unapologetic ways. Yuki is allowing her models to access and to share their embodied archive, and they are speaking their truth. They are proud, they're firm and they are knowing. They're solid and they're popping with fuchsia and truth. By spending time in Yuki's archive, I was reminded of Elizabeth's note to me. To me, the body does not lie. And it was because of that I began to realise, and I started to see through Yuki's lens the truths of the fa’afafine that were hidden in Gauguin’s lies. Their bodies were speaking and Yuki had heard their call. And the same must be said of the bodies of the landscape which Gauguin painted. Yuki's revelations towards his misappropriation – he's trying to tell lies through these models – and these places are a significant example of the body's power to prevail as a source of truth. Yuki knew her own. Yuki knew her home. The body is an archive. Every body is an archive. And every body is fully equipped for memory preservation. This is why Yuki could actually embody and re-enact Gauguin himself. Muscle memory, earth memory, blood memory, bone memory and water memory. We hold a lot and we become a lot. And we hold the history of our people in every cell of our being.

Rosy Simas also actually wrote really beautifully about this just last year. She wrote, ‘I realised how the movements of my childhood of play, dance, ritual and ceremony movements deeply connected to the earth informed the very architecture of my body. As my bones were shaped by gestures, my senses became developed to receive and perceive information in culturally specific ways.’ And this is what I mean about bodies being animate archives. These remarkable examples of Gauguin's paintings alongside the colonial landscape photography exemplify what I mean about bodies speaking: bodies of people, bodies of water, the bodies of the mountains, all speaking their truths. Yuki recognised them because the true archive of her people and her homelands is the source of her knowing. It is their collective embodied knowledge. And Yuki has access to this animate archive because she is a living inheritor and contributor to it. It's really clear that so much of our Indigenous knowing exists outside of colonial archives and exists instead as embodied memory for people and place. Yuki has shown this in the most generous pack-a-punch way. These compositions do more than line up: they fit perfectly, not only in line, but in pace and in tone.