Queering Climate

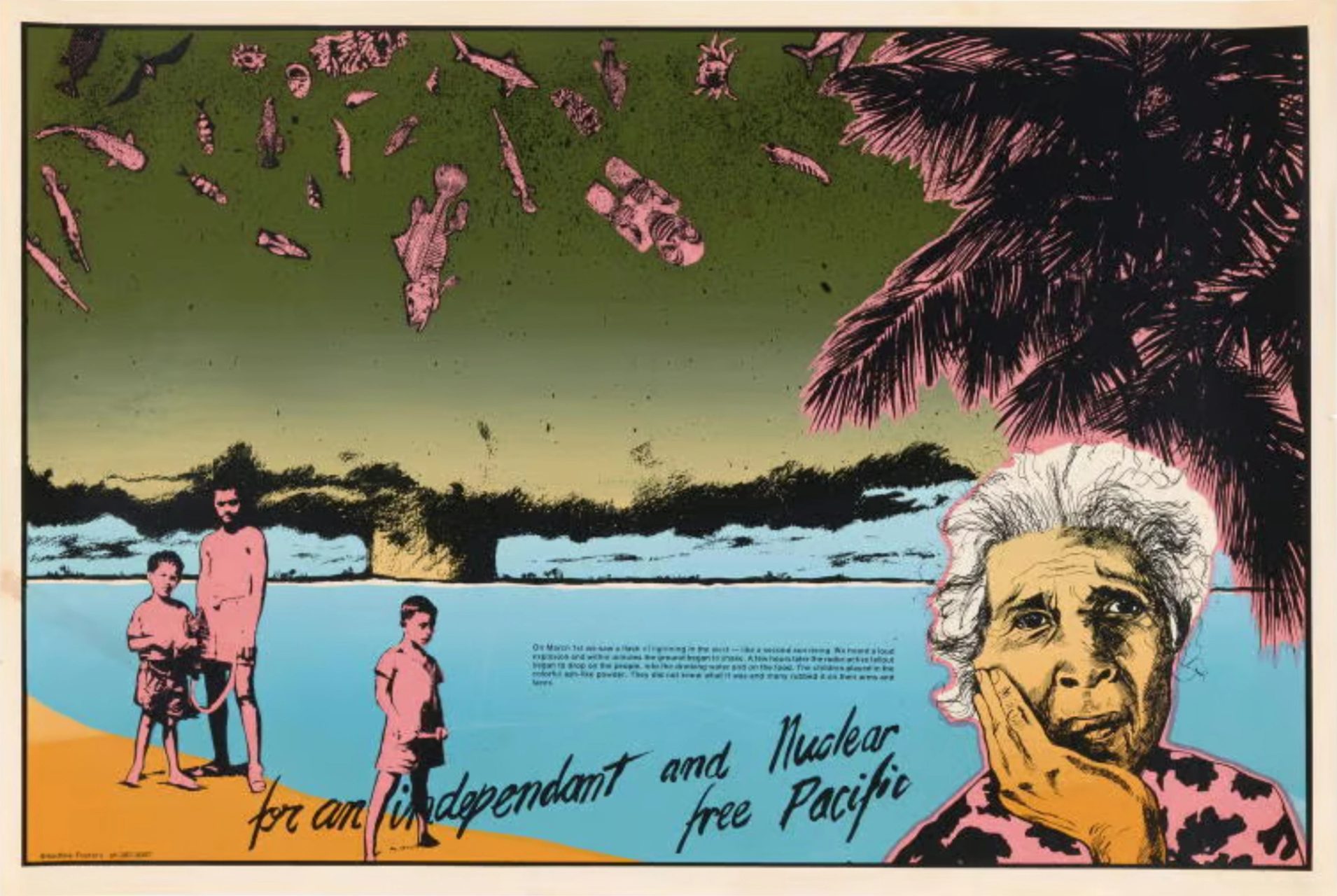

Faʻafafine, faʻatama, trans and queer peoples are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and the wider effects of climate change. This talanoa explores the overlap between the climate and queer movements, and their interconnected struggles within small island environments.

Read and listen to provocations by Professor Katerina Teaiwa and excerpts from the responses of Yuki Kihara, Fagalima Tuatagaloa, Alofipo Fleur Ramsay and Tammi Gissell.

Professor Katerina Teaiwa

‘I'm interested in where the opportunities and possibilities are for kinships, for solidarities between different kinds of marginalised groups, so that all cannot just find but co-create those spaces and places to speak and to thrive and to live.’

Professor Katerina Ko na mauri, yadra vinaka, ni sa bula vinaka everyone. So, I'm originally, like I said, I’m from Fiji. I was born in Savusavu in the northern part of Fiji. I was raised in Levuka, Lautoka and in Suva. My mother is African American from Washington, DC and my father is Banaban and Tabiteuea from Rabi in the north of Fiji and also from Kiribati.

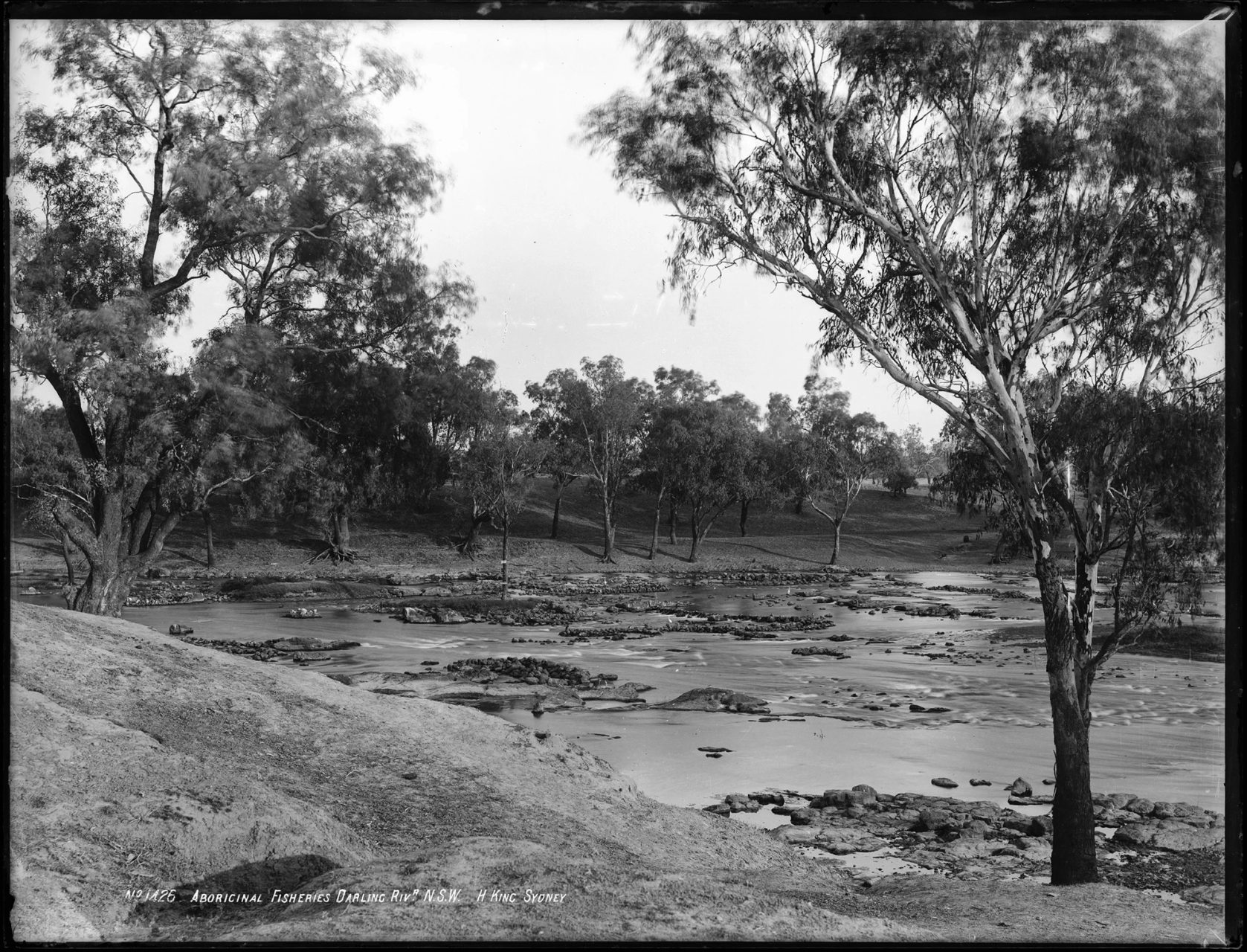

I've spent most of my life studying how Banabans came to Fiji in the first place, and how our island was mined for phosphate by Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom to fuel global fertiliser and farming industries. But as a Banaban and i-Kiribati and Micronesian minority in Fiji, I've always been interested in how people at the margins of state and society navigate and find ways to carve out spaces for themselves in challenging contexts.