Interlaced

‘… I was greatly excited when the laces made their appearance. They were rolled on a wooden bobbin which was not to be seen for all the laces wound around it. Then we would unroll them slowly and watch the designs as they opened out and were always a little scared when one of them came to an end. They stopped so suddenly. First came strips of Italian work, tough pieces with drawn threads, in which everything was intermittently repeated. As obviously as in a peasant’s garden. Then all at once, our view would be shut off by a succession of grille-works of Venetian needle-point … and we looked deep into gardens that grew more and more artificial, until everything was as murky and warm to the eyes as in a hot-house; stately plants which we did not recognise opened their gigantic leaves, tendrils groped dizzily for one another, and the great open blossoms of the point d’Alencon dimmed everything with their scattered pollen. Suddenly, all weary and confused, we stepped out into the long track of the Valenciennes, and it was winter and early morning and hoar frost was on the ground. And we pushed through the snow-covered bushes of the Binche, and came to places where no one had ever been before; the branches hung so strangely downward, there might have been a grave beneath them – but that we concealed from each other. The cold pressed ever more closely upon us, and at last, when the fine pillow lace came, Mother said: ‘Oh we shall get frost flowers on our eyes!’ and so it was, too, for within us it was very warm. We both sighted when the laces had to be rolled up again.’

Excerpt from The Notebook of Malte Laudris Brigge, by Rainer Maria Rilke, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf, The Hogarth Press, London, 1930, p 130–131.

A Czytelnik edition of The Notebook of Malte Laudris Brigge travelled with me on my long journey to Australia in the early 1980s, a refugee from communist Poland under martial law. I chose it not only for its travel-friendly size but because in his only novel, published in 1910, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke offers hypnotic descriptions of objects, including a passage about a secret collection of antique laces, a childhood memory of time spent with his mother narrated by Rilke’s alter ego Malte, a young Dane in Paris.

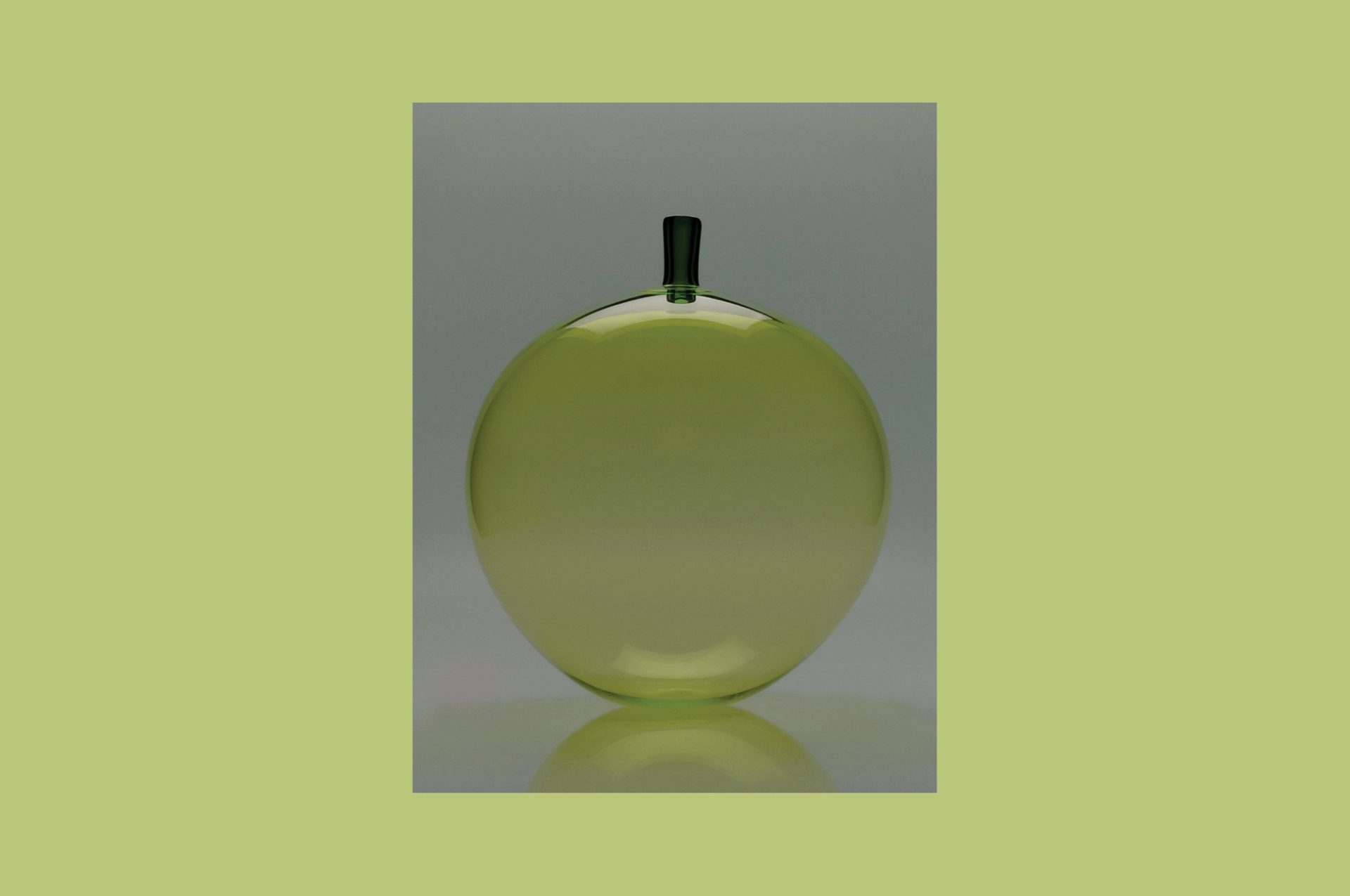

In Sydney, I lost sight of my travelling companion. English language books were now scaffolding my world, alongside Hanna-Barbera koalas I painted on cells in the pre-digital aura of a St Leonards animation studio, an alluring hub for young ‘creative’ migrants. Then, in 1985, the Powerhouse arrived in my life. As a conservator I was asked to devise display methods for strips of fine lace. With Rilke’s passage resurfacing in my memory, a big adventure of exploring the museum’s sensational holdings had begun. From lace to textiles and ceramics, I was deep diving into that incredible storage universe where, week by week, month by month, thousands of objects were presenting themselves to me, grand and humble, familiar and foreign: shelves of hats, shoes and rococo fans, Murano glass, Egyptian amulets and Greek amphoras, Australian goldfields jewellery and magnificent musical instruments alongside massive salt-glazed stoneware pots fit for Gulliver, Doulton’s industrial marvels from England, Wedgwood, Sevres and Meissen porcelain — what was that baroque bust in Meissen porcelain hang about with white mice (Object No. H5127)? I went to Germany to find out1.

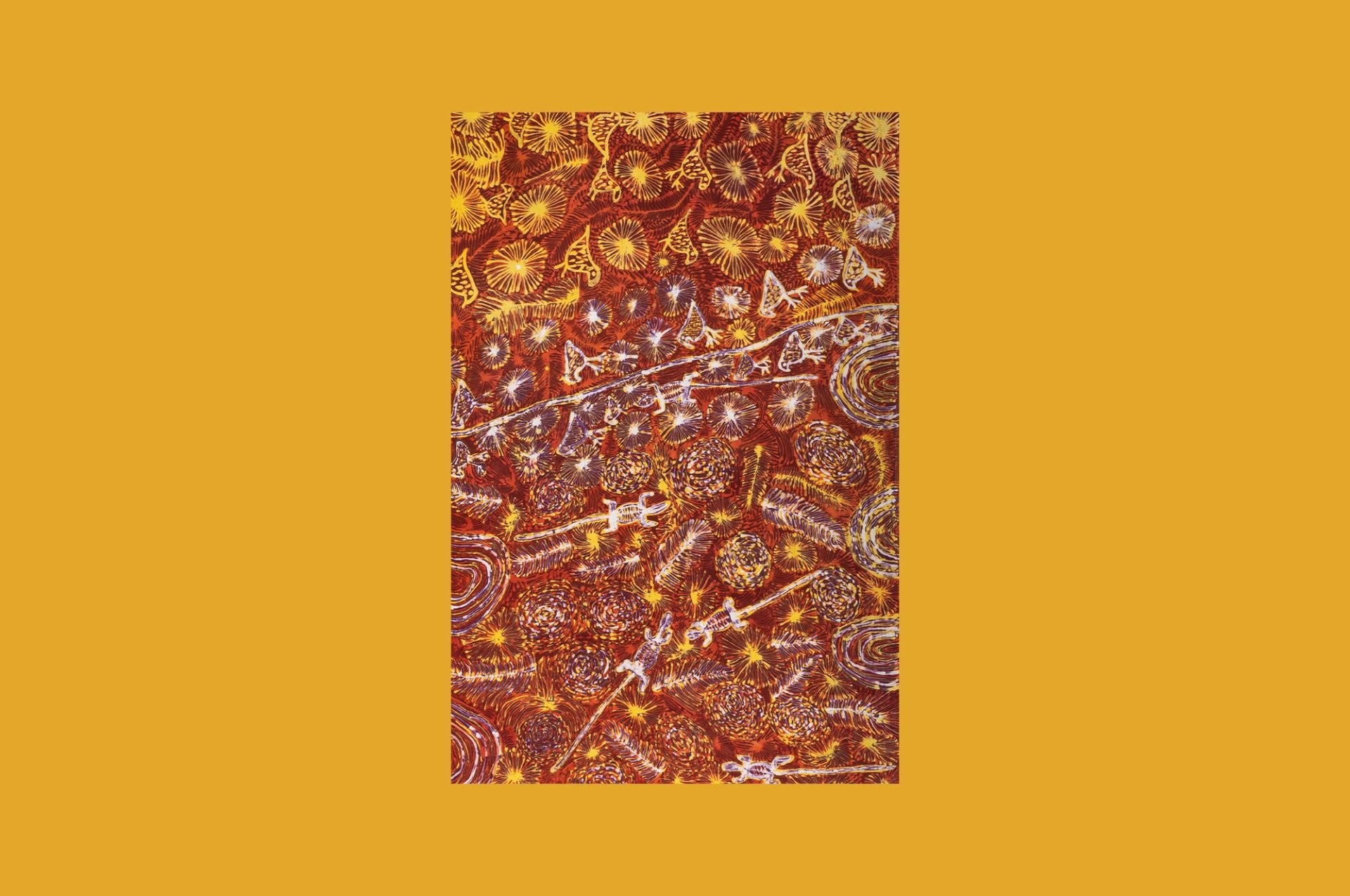

Now a curator, the collection began unspooling itself before me like a never-ending ribbon; so many stories, perennially changing with each new piece of research, acquisition, exhibition. The humbling First Nations perspectives, the revelation of Australian contemporary studio practice, the growing awareness that today’s answers may only be temporary, that understanding may change from the last time questions were asked.

After almost three decades as an arts and design curator, 1001 Remarkable Objects presented a welcome opportunity to look at the collection through a fresh lens alongside colleagues from performing arts and antiques backgrounds. As draft object lists unfolded, four underlying themes emerged: nature, power, movement and joy. It was fascinating to observe the transformative power of our unorthodox groupings and ‘conversations’ between objects from diverse fields, eras and cultures; and how, at times, our individual notions of context, and what was significant, mellowed or shifted.

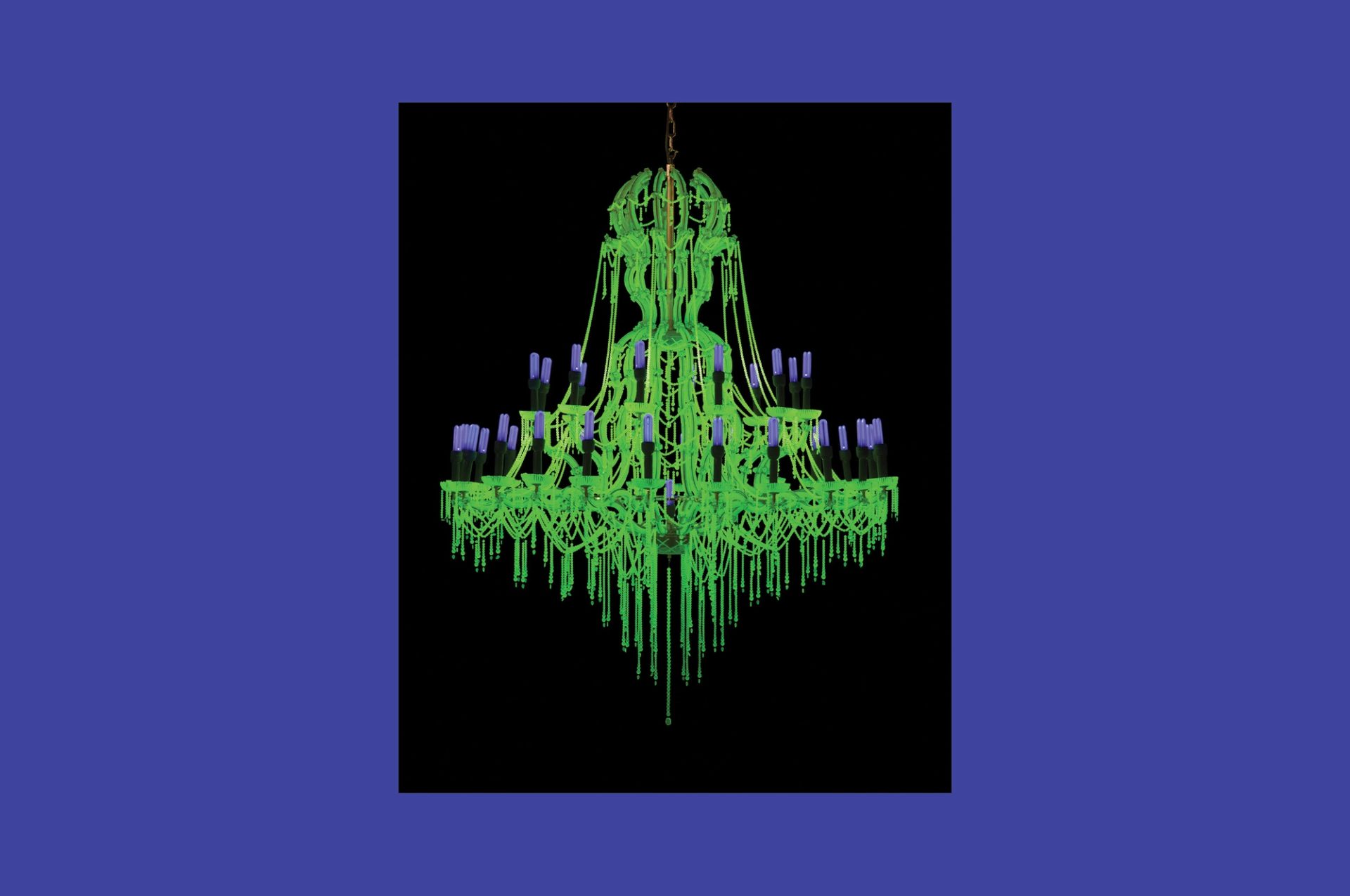

Our three exhibition designers, Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace, all acclaimed scenographers from the theatre world, imaginatively marshalled the contents into a labyrinthian procession of some 30 spaces, each with a distinctive mood. All presenting a stunning plethora of objects and stories that could be powerful or light-hearted, ordered or alluringly chaotic.

When design drawings for the interconnected gallery spaces began to appear on my computer screen, Malte’s unfolding roll of lace again came to mind. Later, as I walked under the numerous archways, corridors and meandering paths of the exhibition space, my thoughts drifted to lace itself.

There is a splendid lace work included in 1001. An Italian needle-lace panel from the 1600s depicting ‘Judith and Holofernes’ (Object No. A5335), it is, in the words of Thomas Crow and Richard Meyer, a time traveller from the past with contemporary relevance that ‘renders the past newly present’.2 Judith is shown brandishing her sword and holding the Assyrian general Holofernes’ head by the hair (woven with real hair). This marvellous panel belongs to a category lace historians refer to as ‘threads of power’, not only because wearing fine lace used to be closely regulated by the powerful elite, but also because some lace (most were made by women) contained defiant images and messages, ‘evidence of women’s simmering rage and fantasies of revenge’.3 We cannot help but see it in the context of the MeToo movement.

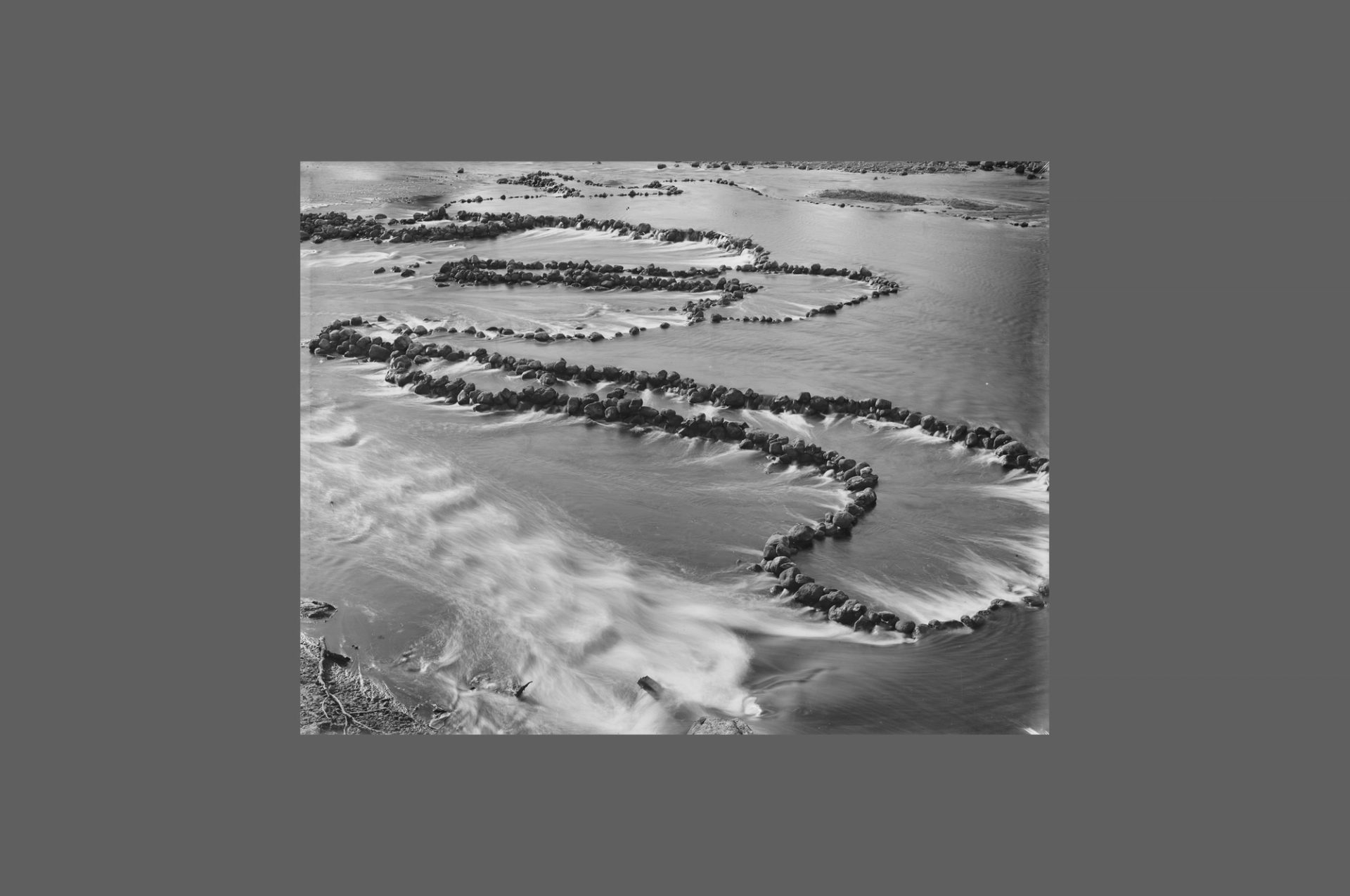

1001 also included numerous objects in different materials that draw on the idea of lace, including some contemporary works by artists and designers with an interest in lace-like structures and their affinity to patterns found in nature. Some take it a step further. Nature and concerns over human induced habitat destruction are increasingly present in the practice of many of the contemporary artists included.

A hand-cut titanium neckpiece made by Bethamy Linton in 2010 (Object No. 2013/11/1), resembles an Elizabethan lace collar or ruff and highlights the plight of the critically endangered Euphrasia arguta, an Australian plant presumed extinct until rediscovered in 2008.

At once beautiful and terrifying, Timothy Horn’s 2 metre wall sculpture Gorgonia 15, from his 2018 Coral Works series (Object No. 2018/40/1), looks like an Anthropocene fossil from the future and comments on the calamitous effects of climate change on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, one of UNESCO’s seven wonders of the natural world.

The work’s title refers to Gorgonian sea-fan coral named after the mythological snake-haired monsters who turned people into stone – Horn’s take on ocean warming that petrifies the coral reef, rendering it lifeless. Its fabulous form, a hybrid of bony-branched silvery coral and oversized jewel, is based on a French baroque drawing for a girandole earring by the court jeweller to France’s Sun King, Louis XIV.

One of the most recent acquisitions included was Japanese- Australian ceramic artist Kenji Uranishi’s Walking in the Forest (Object No. 2021/81/1). Inspired by one of his dreams during a prolonged COVID-19 lockdown, the white porcelain sculpture is constructed from interconnected elements that form a sweeping circular formation which appears to be in perpetual motion. Uranishi compares it to a ribbon of film on a reel. This mesmerising modular circle, a structure that can be assembled and reassembled, serves as a metaphor for the folding nature of time in an exhibition that avoids chronology and has no beginning and no end.

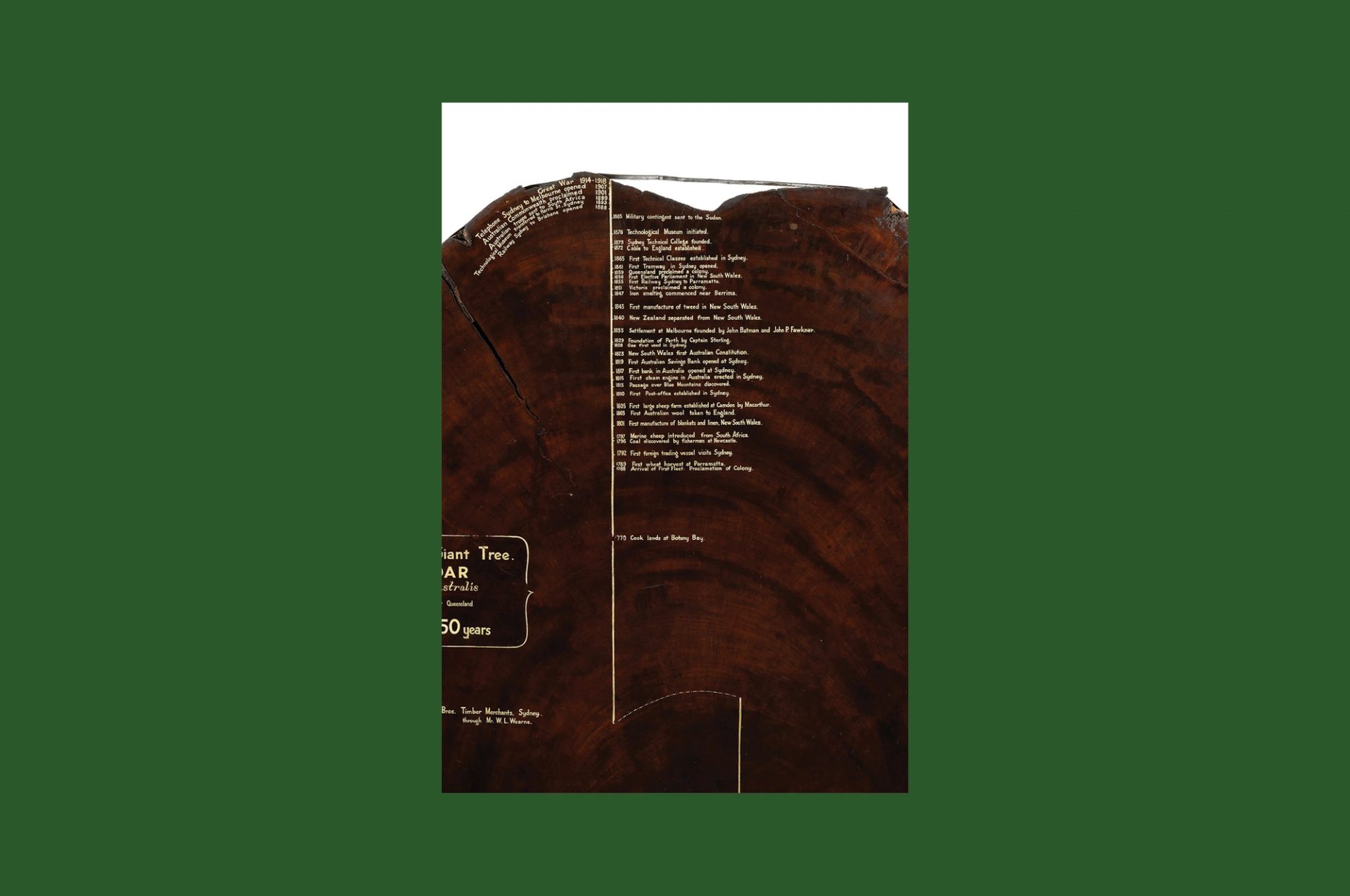

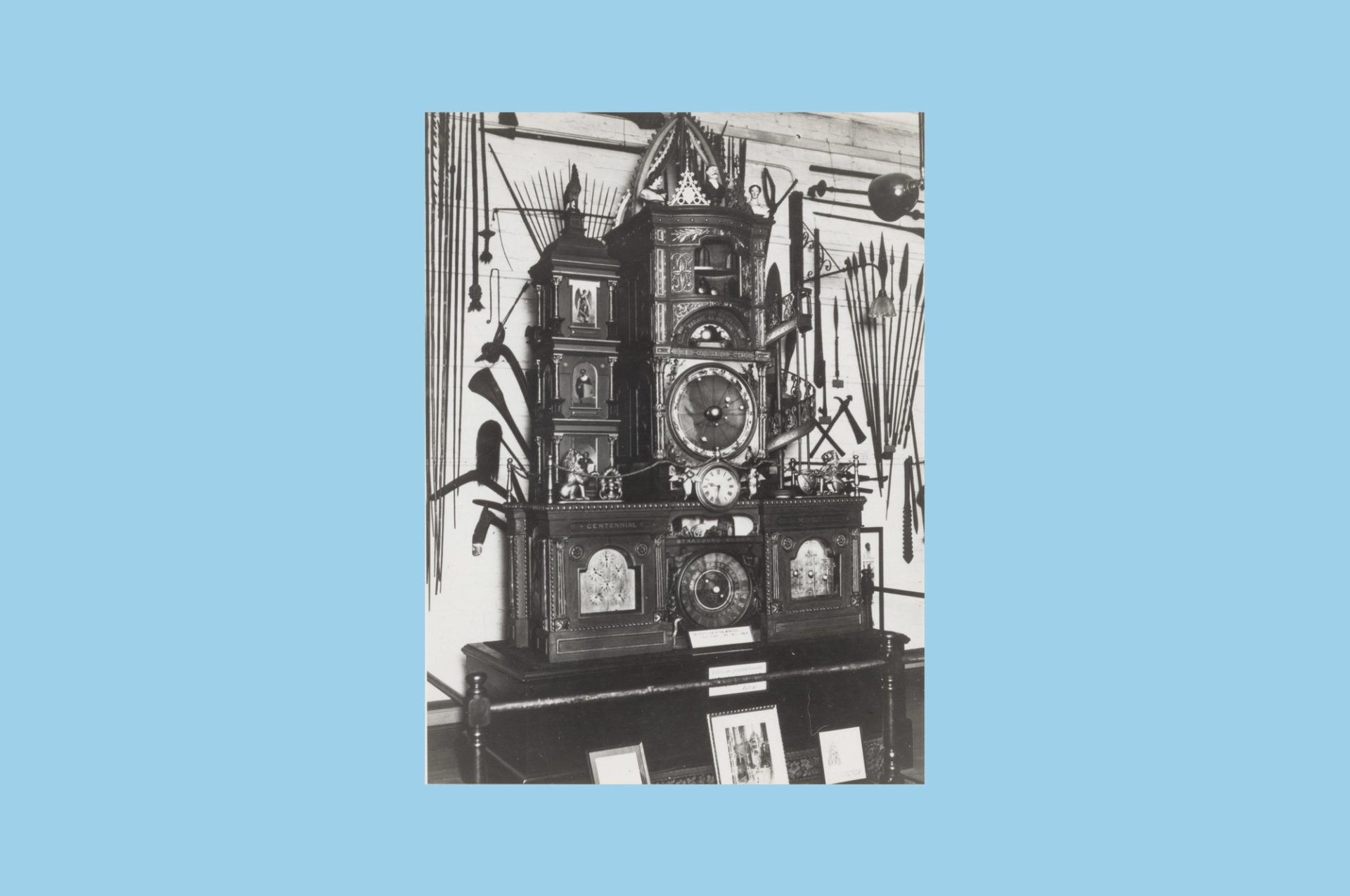

Not far from Uranishi’s work, we installed a wall of grandfather clocks, the earliest from the 1600s; some now permanently silent, others still keeping time. Whenever these clocks stop, before conservators wind them once again, their silence seems to mark an extraordinary moment in history. As curators we are part of a shift whereby practitioners of many cultural disciplines are searching deeper than ever before for new ways of engaging with the past and shaping the future.

1001 Remarkable Objects celebrates the Powerhouse Collection as a lively organism that keeps redefining itself with each look, each visit, each memory. A wondrous bundle of objects and stories from across time, place and culture that endlessly interlace in unexpected ways.

Footnotes

1 E Czernis-Ryl, ‘The golden years of Meissen porcelain and Saxon jesters: the Schmiedel bust in Australia’, Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz (Bulletin des Amis Suisses de la Ceramique), Mitteilungsblatt nr 104, October 1989, pp.5–11

2 Richard Meyer, What Was Contemporary, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, 2013, p 21

3 Eve M Kahn, ‘On point – the wearing of lace has always been tied up with social status’, Apollo, 31 October 2022, apollo-magazine.com Accessed 3 July 2023

About the Author

Eva Czernis-Ryl is an art historian and award-winning curator at Powerhouse whose interests focus on connections between applied and fine arts, craft, design, technology, architecture and contemporary culture. She has published on subjects ranging from German baroque sculpture and Italian design to Australian studio practice. She is a member of the Attingham Trust and three-time Copland Foundation/Nina Stanton Scholar. Czernis-Ryl also holds a position on the Editorial Board of Garland magazine. Recent exhibitions include Clay Dynasty (2021—23), Fantastical Worlds (2022) and 1001 Remarkable Objects (2023).

Powerhouse Publication: 1001

This work appears in the latest Powerhouse Publication, 1001 Remarkable Objects. A celebration of the scale, breadth and relevance of the decorative arts and design collections held by Powerhouse Museum it catalogues the eponymous exhibition that opened at Powerhouse Ultimo, 26 August 2023. The publication opens with a series of 32 still life images produced by photographer Lauren Bamford in collaboration with art director and stylist Sarah Pritchard. It is punctuated by 15 narratives, from the four curators plus 11 Australian authors commissioned by Powerhouse to respond to one or more remarkable objects.