The Creative Impulse

I was eight years of age, going on nine. Still in short pants. I had travelled to Sydney once before on a family holiday to Bondi, but there was a more significant purpose to this second visit. I was being despatched to boarding school, ostensibly to receive a better education than the one available at the Convent of Mercy in Brewarrina, a pipsqueak town on the Barwon River, 787 kilometres north-west of the Big Smoke.

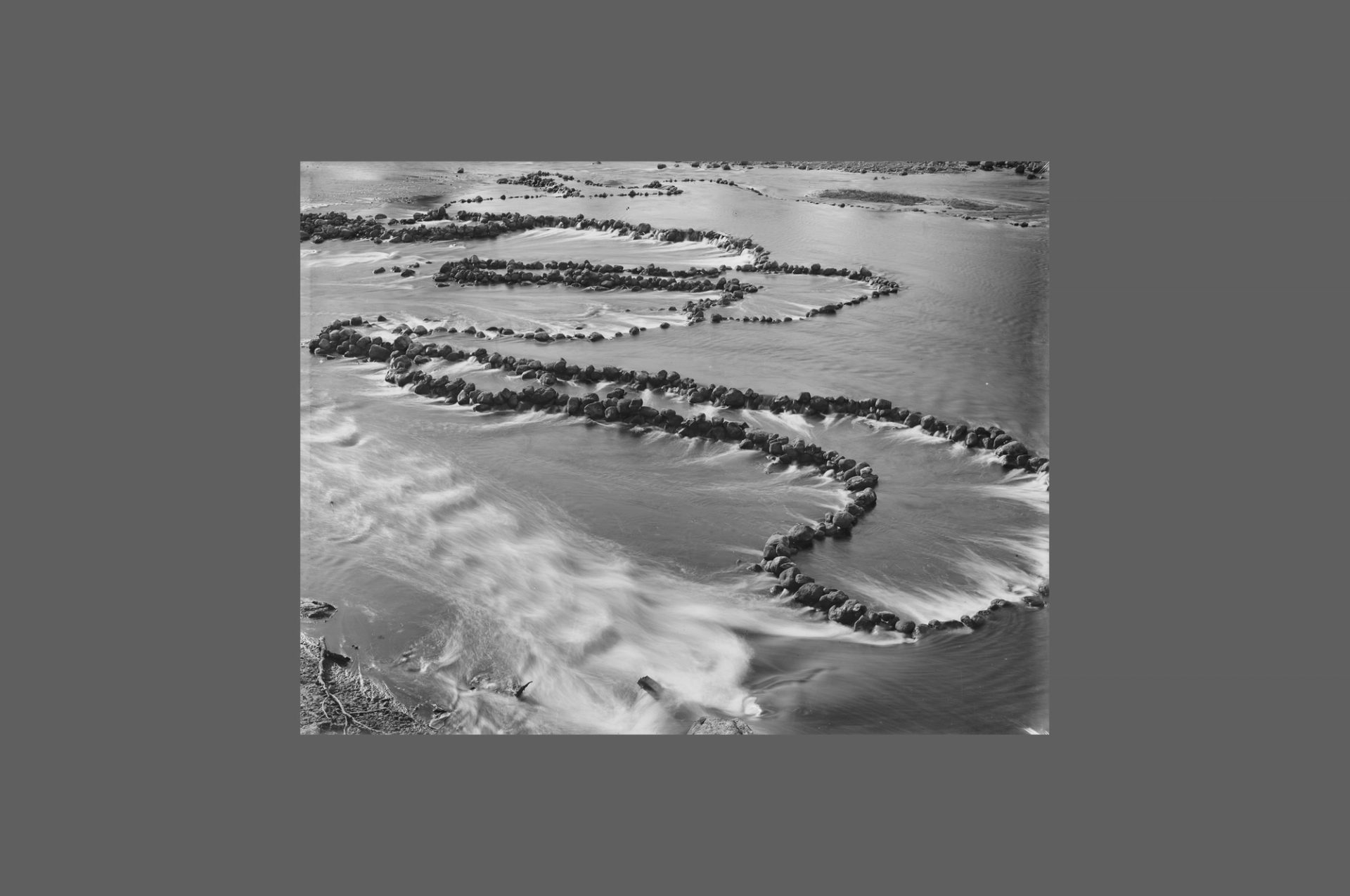

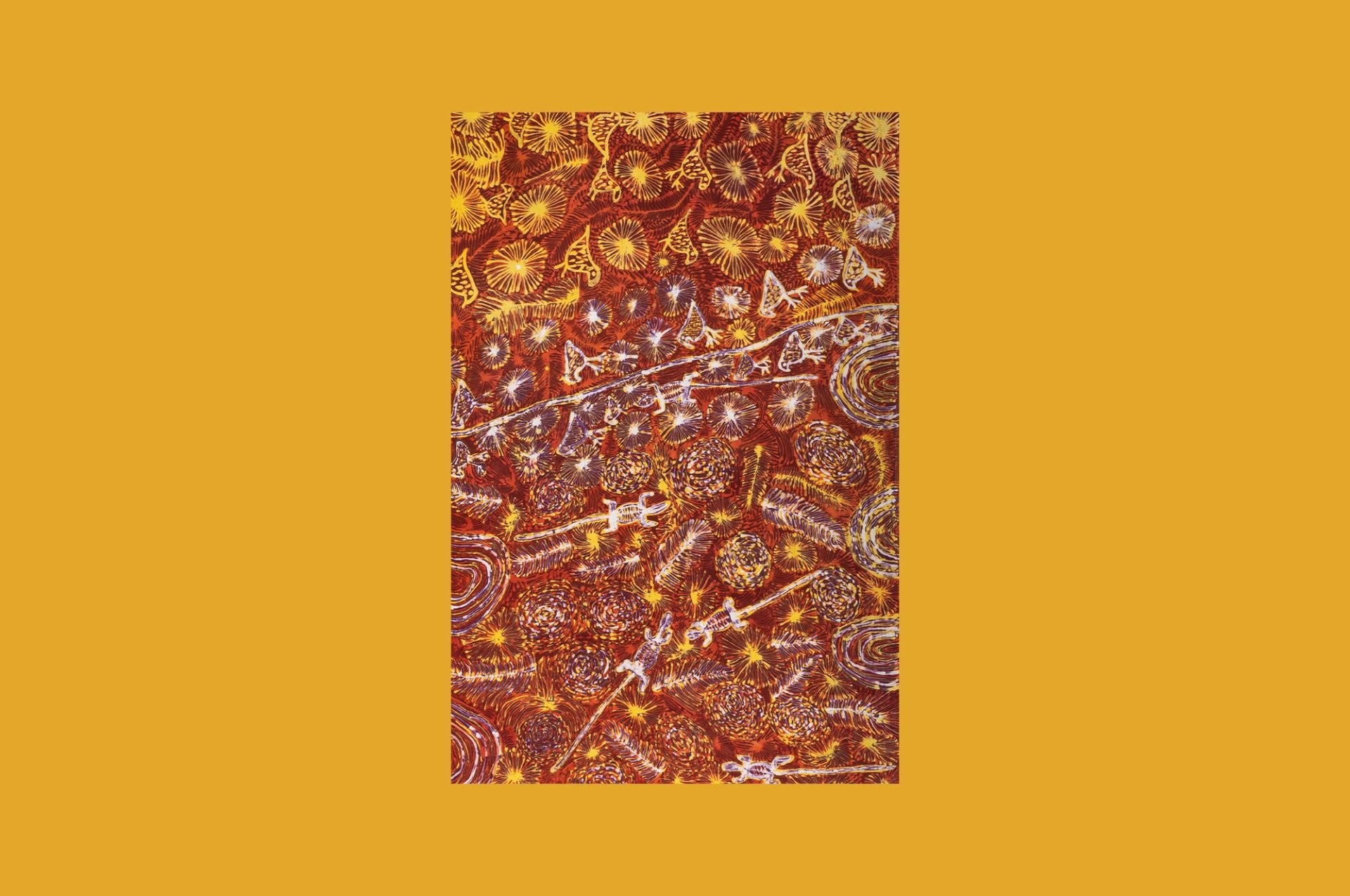

Today my home town is best known for the local ancient fisheries, an intricate series of stone weirs and ponds the Traditional Owners first devised tens of thousands of years ago. Not that we learned about this ingenuity in school. An image of the Brewarrina fish traps, photographed sometime between 1880 — 1923 (Object No. 85/1286-721), was one of the first objects selected as we embarked upon curating 1001 Remarkable Objects.

Brewarrina was, at the time I departed for school, simply the farthest-flung destination on the New South Wales railway network, the end of the line as ‘twere.

I left at 8.20am on a sunny Friday morning and arrived in Sydney 23 hours later, met by my grandmother and my uncle, her elder son. I was to be delivered to my new school the following Monday morning and, by way of diversion, was taken to what was then known as the Technological Museum in Harris Street, Ultimo. And it was there that I first sighted the ‘Strasburg Clock model’ (Object No. A44), which fascinated me as it has generations of kids for over a century; perhaps the most loved and best remembered of what is now known as the Powerhouse Museum’s eclectic holdings.