ZC One of the reasons I've been so interested in plants over a long period of time is because the more I started to learn about my mobs and mobs from all over Australia's sort of cultural practice in relation to plants, the more I started to realise that plants really have been, from my perception, the backbone of our ability to survive, thrive, adapt, and live here for the longest time imaginable. Because we've used plants, not just for food, not just for medicine, but for technologies and all of the things that we really need to stay strong and healthy. And the vitality of Country has allowed us to adapt through some of the most incredible situations.

We know that the time that we've been here is badly conceptualised in that it relies on notions of the Western scientific lens. Whereas our mobs say we've been here forever. And when I was at school, I remember reading 20,000 years. And then I remember reading 25 and then I remember reading 35 and then it went to 40 and you know, then 65. And then there's a lot of things being investigated recently that point more towards 120, 140, but they haven't been substantiated through the Western lens just yet. But I think we have been here forever. That's what our old people tell us. And we have stories for everything. And every mob says we've been here forever through their oral traditions. So, I'm just really looking forward for that information to be accepted by all Australians.

DD I work with the archeologists out this way and we don't do any extensive archeological digs, but the surface stuff shows that our people have been in the region for 45,000 years continuous. So, we've never had to move. We've had food and resources stacked on that. We've never had to live a nomadic lifestyle and I'm sure if we ever let archeologists, and I don't think it'll ever happen because we're so reluctant to let people in to dig down, they would find that, yeah, we have been here forever. There's a never-ending supply of proof just underneath the soil. And it just shows that, you know, we did adapt to the life that was around us, the plants we continuously adapted, we farmed, we kept livestock. It's all, it's all there. It's all, it's all proof.

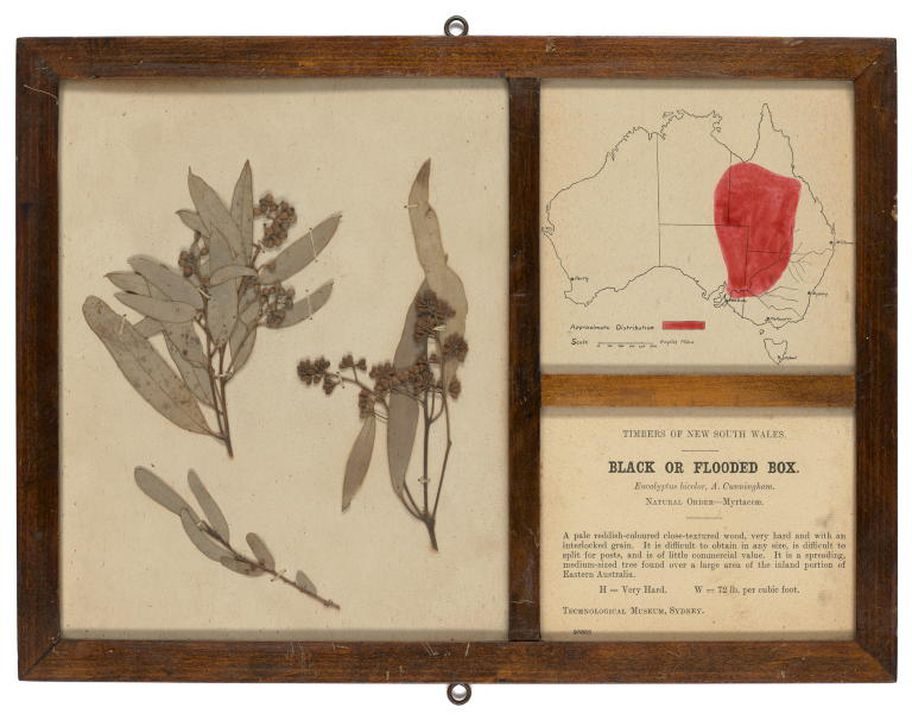

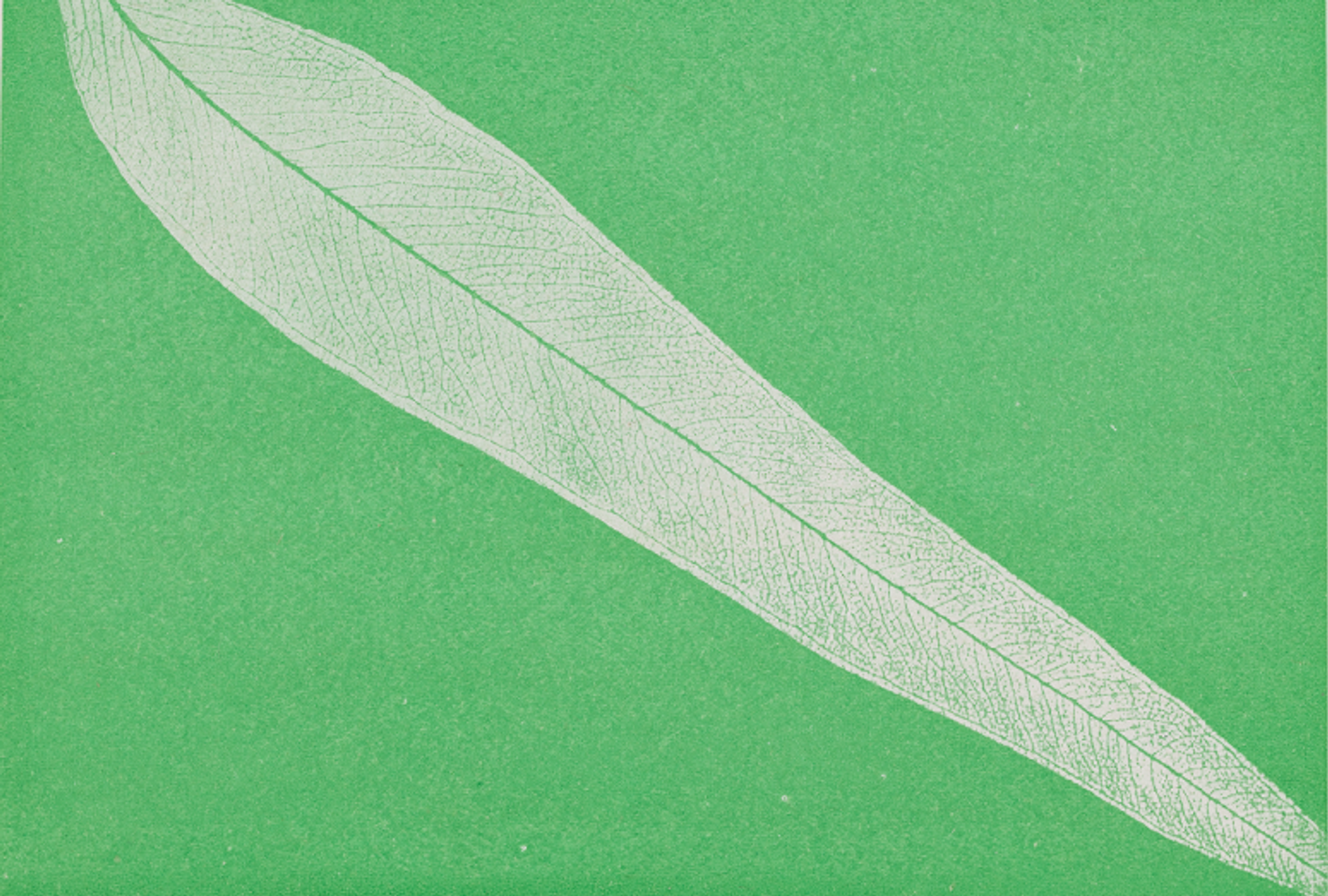

ZC Going back to plants. I just really, really believe that they have been the backbone of our longevity and plants just are the most incredible resource because there's so many things that they can do. Even if you just think about the river red gum.

EM For the Barkandji, and particularly for David Doyle, the river red gum is deeply significant. It is also highly useful, and its material language extends to many areas of life and culture.

DD So, some of the uses of course, were large scale canoes, which you can find photographs of on the Darling River in lots of different places. We still have some in museums that are well and truly over 100, 140 years old, that look like they could go on the water today and still float, no problem whatsoever. Right down to smaller coolamon shape bowls. And I'm only talking about bark here. There's smaller vessels that we could take off the tree quite easily to carry a baby, carry food, used for winnowing seed, for mixing bowls, mixing ochre, carrying fish, cooking in. Like I said, that's just the outside of the tree. As well as some of that bark, having medicinal properties for colds, flus, coughs, sore throats. The roots were used for boomerangs or clubs. You can walk along the river where the roots are exposed and see where our old people had taken them off with stone axes, with metal axes and were still taking them off now with chainsaw.

So, you know, that adaptability, we also use the leaves, of course, for medicine, eucalyptus leaves. Then the amount of animals that live in it, you know, possums, we've got insects, the grubs, the birds that live in it, the termites that live in it. So all of these things housed in one tree shows how important they were. Plus, then they provide us with shade. They provide us with heat. They provide us with shelter. They provided us with a safe place to have babies. They provided us with places that we could cook inside as well as fuel the fires. I teach quite a bit of that in cultural practice.

When I go back to my hometown of Meninde and incorporate that into teaching the school kids, one of them being, making bowls out of either the bark or the wood and red gum's one of my favourites. You know, it's one of those hardwoods. That's still soft enough to allow kids to work at easily, but hard enough that it's gonna last you for a lifetime. The joy you actually get out of just sitting down with that piece of wood, it's telling you a story. I carve sculpture with it as well. I've tried to carve a kangaroo from a piece of wood that I found on the edge of the river. And it turned into a fish. The trees got their own stories that they've got their own wheels. And I only use wood that's naturally filled from a storm or from a fire. One of the things that I really like to do now is use some of the huge red gum that we have. And I say huge because they're massive. They're, you know, eight, nine feet across. So that's, you know, over three meters and they've been through bush fires. So, you find dead bits that are burnt and incorporating that into a piece of sculpture and into a bowl. So, it still has its story. It still can tell its own story, but you're just helping it by highlighting some of those bits and pieces.