Grace and flavour: Karen Martini

Grace and flavour

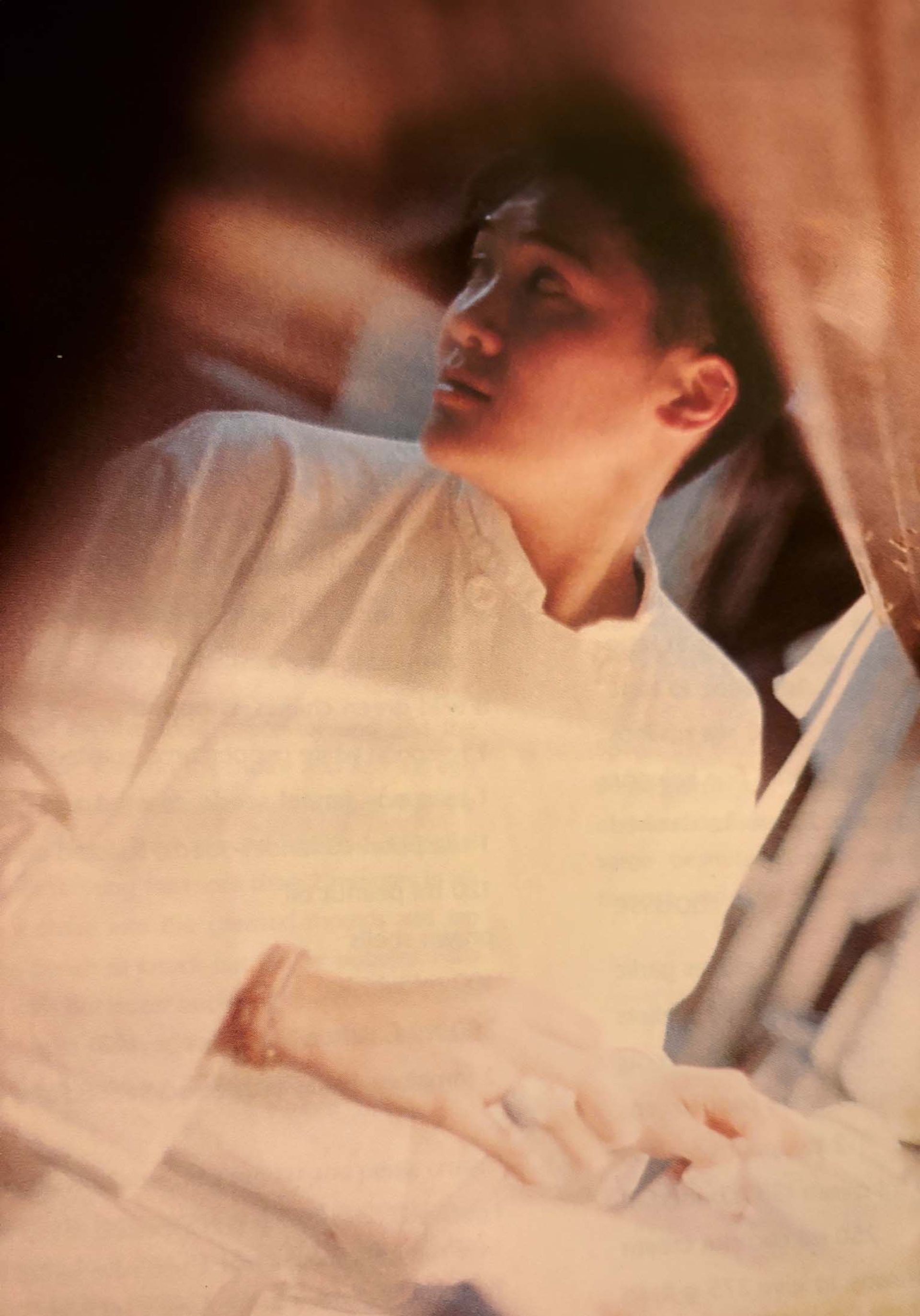

In this interview for the Australian Culinary Archive Karen Martini reveals how being constantly hungry as a teenager led to a career as a leading chef, writer and passionate teacher of home cooking across all media.

Julie Gibbs Karen, you wrote a menu when you were 15. Tell me about it.

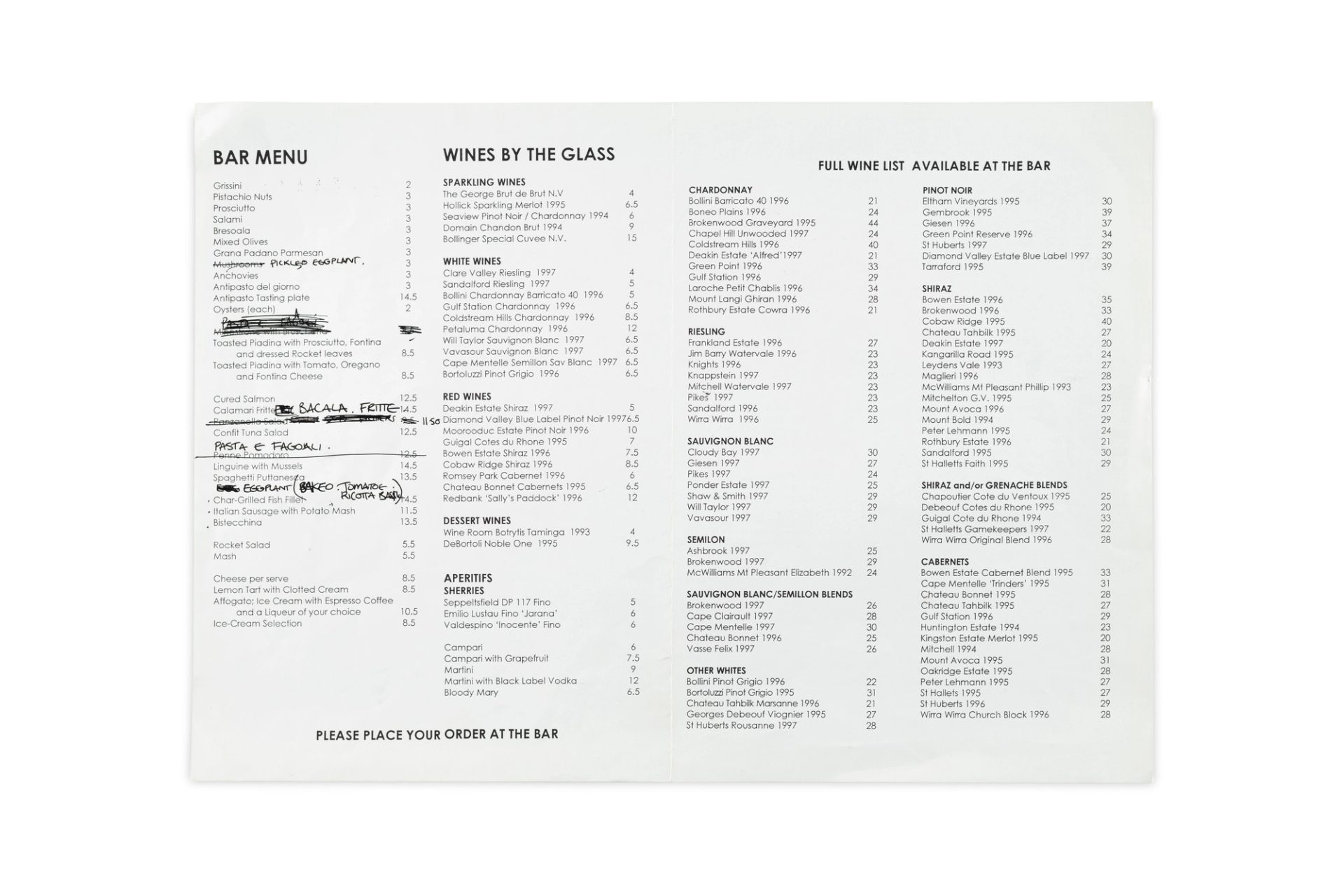

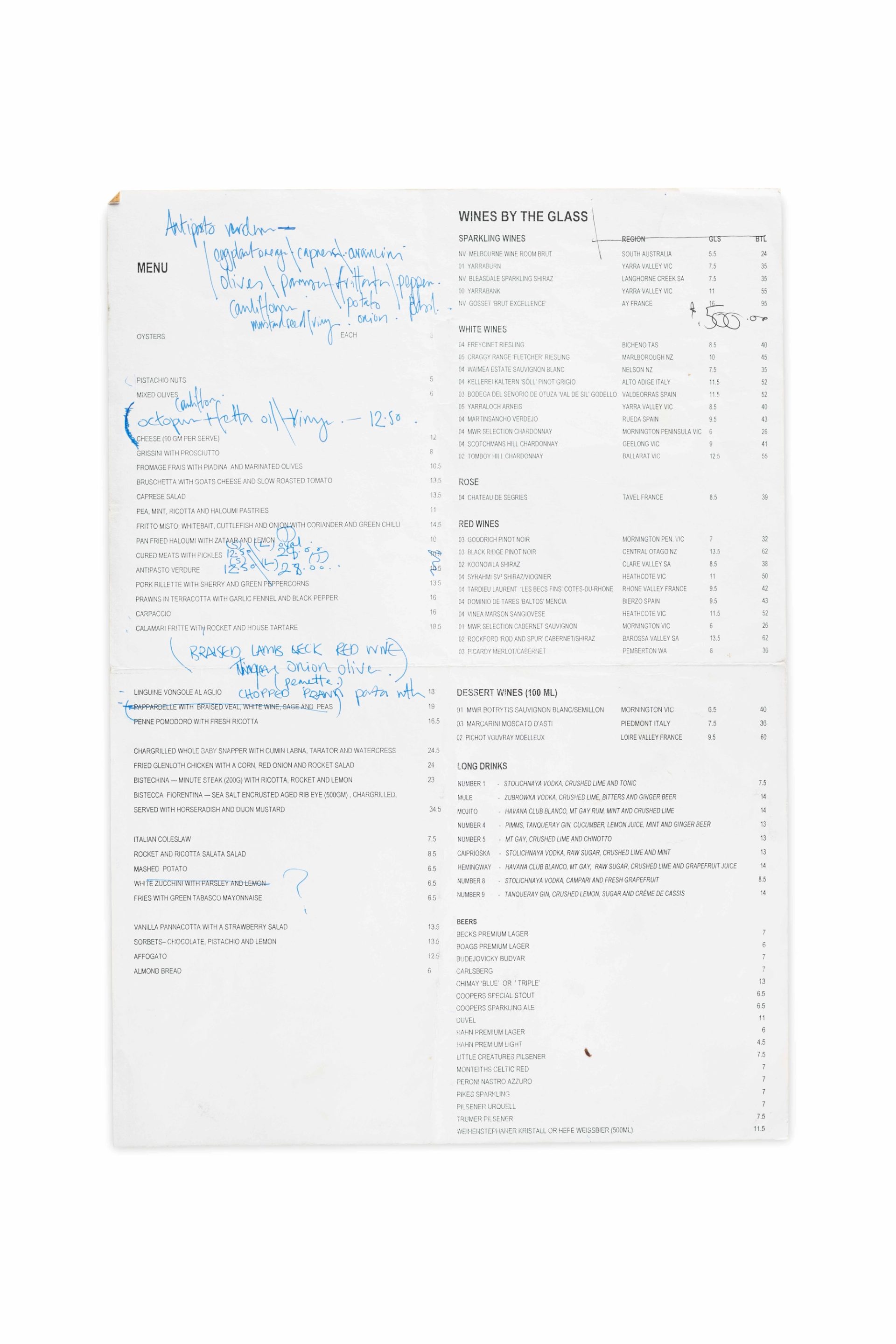

Karen Martini I have fond memories of being constantly hungry, hovering in the kitchen to find out what we were having for dinner. Actually, coercing the decision. The opportunity to do work experience with Jacques Reymond at Mietta’s, a three-hat restaurant, solidified the idea of starting a career in cookery. The bug started in a serious way working in a hierarchy of a kitchen and the symphony of food being made, the formality and the respect for produce. I thought, ‘This is the world for me.’ I was 15-and-a-half, finding an apprenticeship, studying at William Angliss [Institute] and writing that menu. It was one of our first projects: you’re going to work in a restaurant, what’s your menu? Trout amandine, avocado mousse and poached pears.

JG Is that Jacques’s influence in there?

KM Yes. It had a French lean, if you like.

JG What was the trajectory of restaurants that you worked in before you went out and had your own restaurant?

KM After work experience, I wrote to Mietta O’Donnell and asked for a position. She told me, ‘Go back to school. You’re too young.’ I got that from a few different people and so started work at the Austin Hospital, quite a step down from a three-hat restaurant, one could say, but I had my eye on the prize. I progressed to a hatted restaurant, Pourquoi in Albert Park. I was chasing people that really were passionate about what they did and how they positioned themselves in, I suppose, the infantile beginnings of the food environment. Then in 1989 I landed at Tansy’s, a three-hat restaurant. Most terrifying trial day in my entire life. I succeeded, I think, from a point of view of determination and the willingness to learn. I had struck it big.