32 Remarkable Objects

‘Lauren and I definitely have a huge overlap in interests and experiences which makes working together a breeze. In saying that, we both have our unique perspectives and skills, and this keeps things interesting. I think we push each other in the right ways but also really trust each other.’

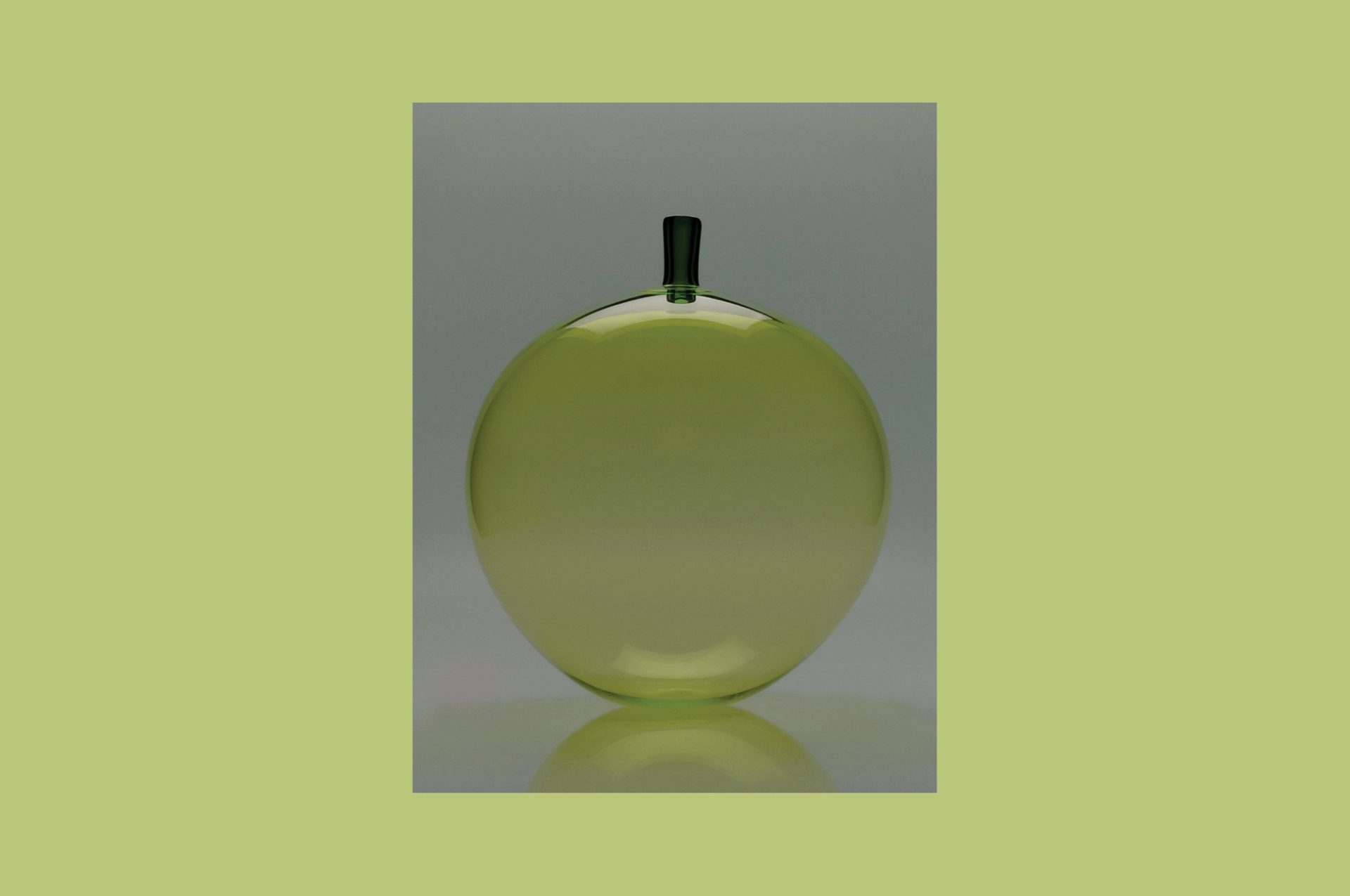

To look at the photo collaborations of Lauren Bamford and Sarah Pritchard, it is difficult to see where their individual contributions begin and end. Their object-based imagery is often beautiful and funny at the same time. Simple compositions become more complex on second glance. Elements of high and low culture collide, becoming one. Individually, each artist has forged a successful solo career from their base in eastern Australia: Bamford as a still-life and documentary photographer with a background in travel and lifestyle; Pritchard as an art director and stylist in the world of luxury fashion. In the last few years, however, they have become sought after as a creative team. Recent commissions have seen a snow shoot for French fashion house Jacquemus (with accessories playfully bedecked on skis), and a billboard in Madrid featuring a Loewe perfume bottle sinking into watermelon flesh.

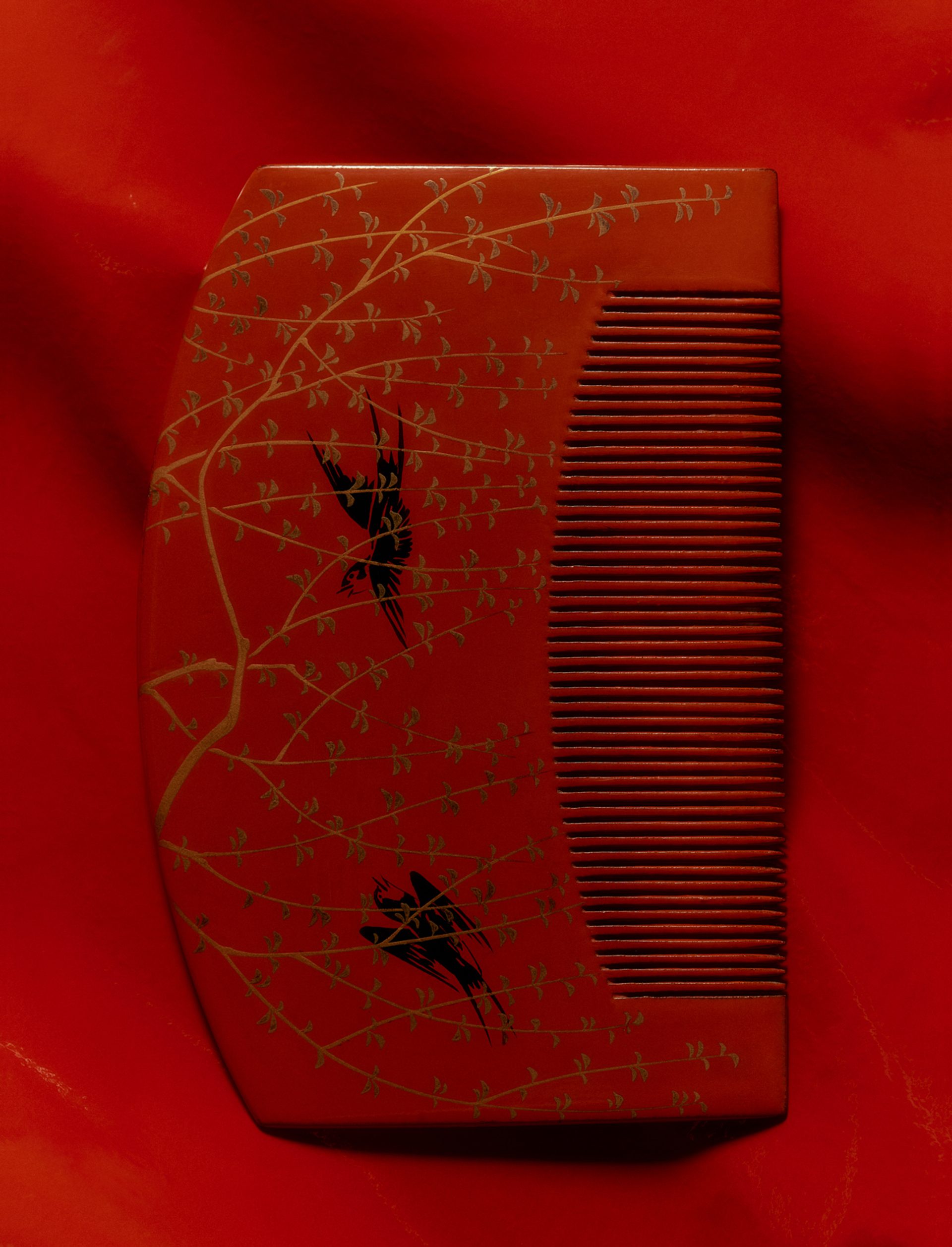

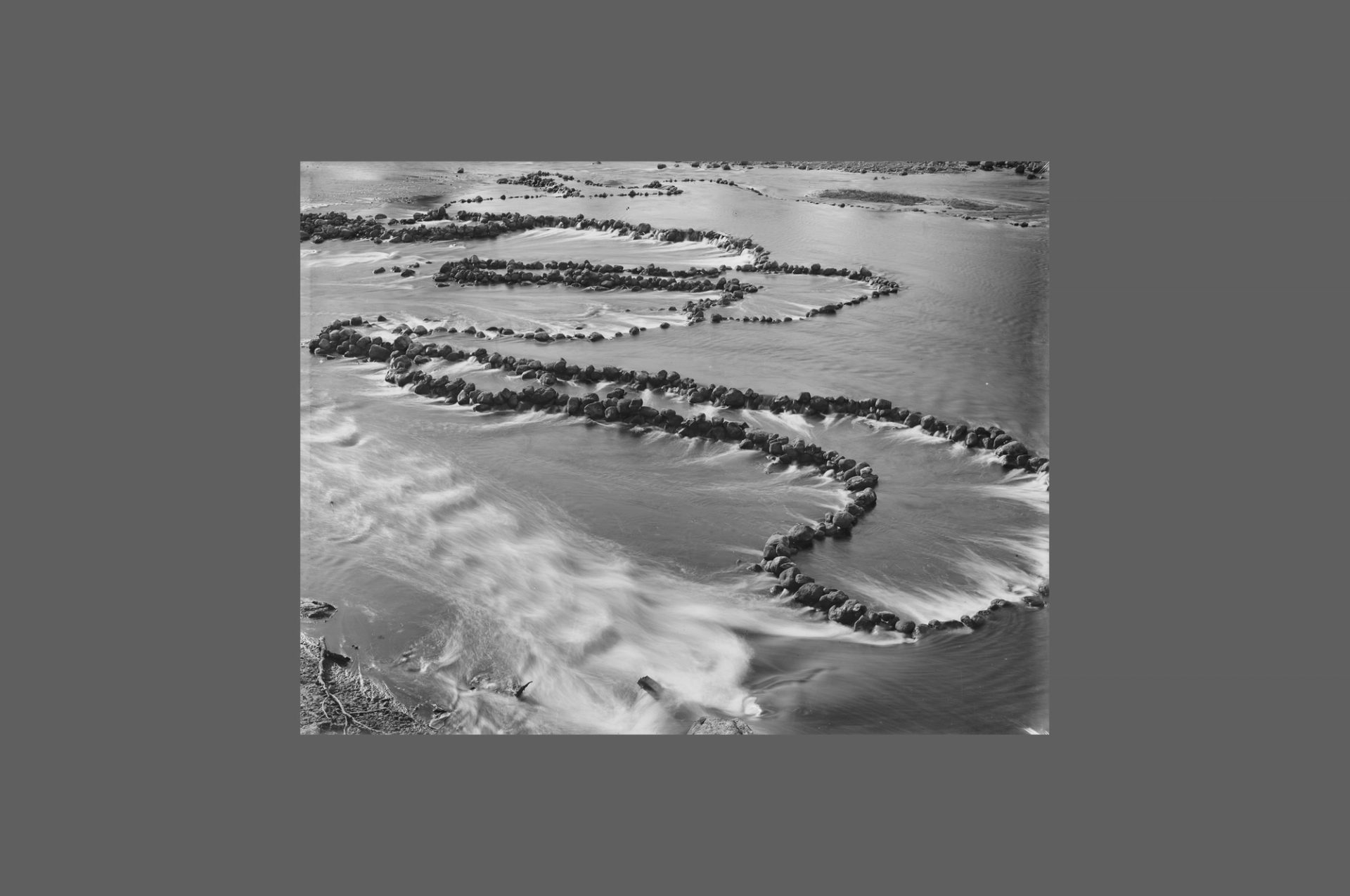

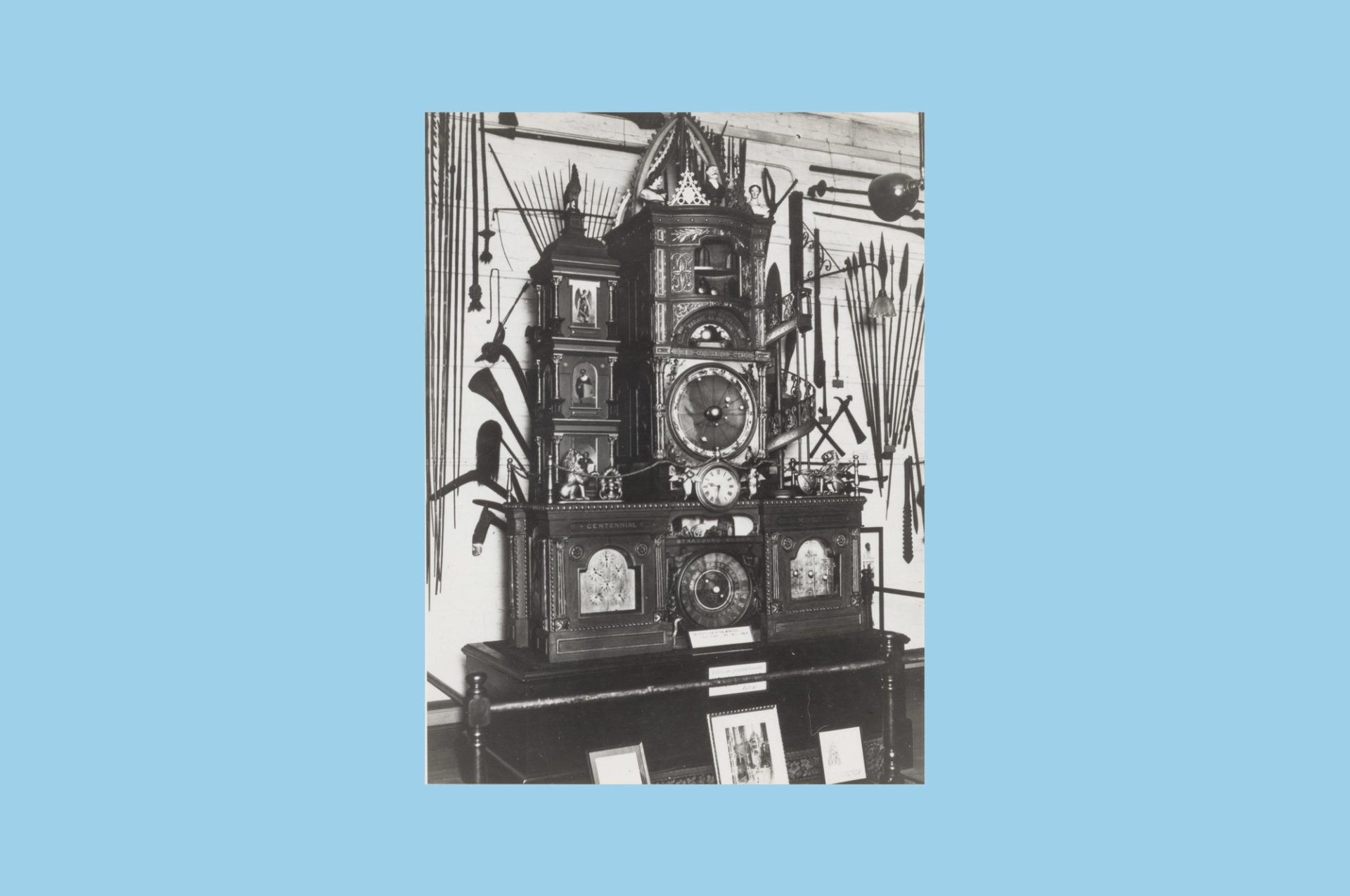

Because of their sharp eyes and distinctive approach to still-life photography, Bamford and Pritchard were commissioned by Powerhouse in 2023 to create a suite of images for the 1001 Remarkable Objects book to accompany the recent and eponymous exhibition at Powerhouse Ultimo. Selecting 32 objects in collaboration with the museum’s curatorial, collections and conservation teams, Bamford and Pritchard managed to capture a surprising liveliness in their mainly inanimate subjects – from the miniscule (a Mickey Mouse brooch) to the monumental (an architectural model of Macquarie Lighthouse). In the following interview with Powerhouse senior editor Michael Fitzgerald, they tease out the threads of their collaborative practice, the blurring of their commercial and artistic work, and what for them makes the still-life genre come alive.