Xin Liu: Cosmic Metabolism

To celebrate Sydney Science Festival 2024 Powerhouse Associate Ceridwen Dovey interviewed this year's keynotes, Susmita Mohanty, Maya Nasr and Xin Liu.

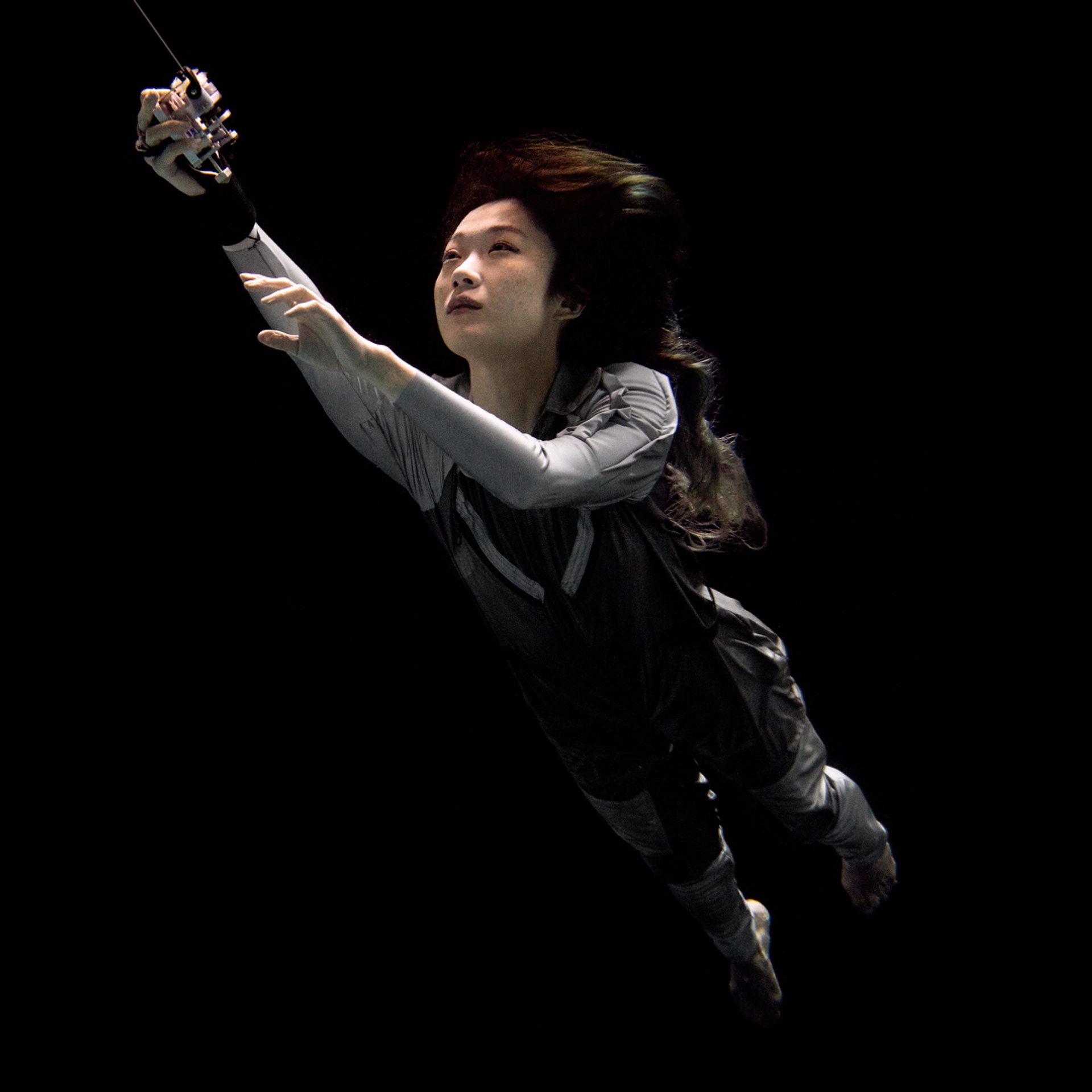

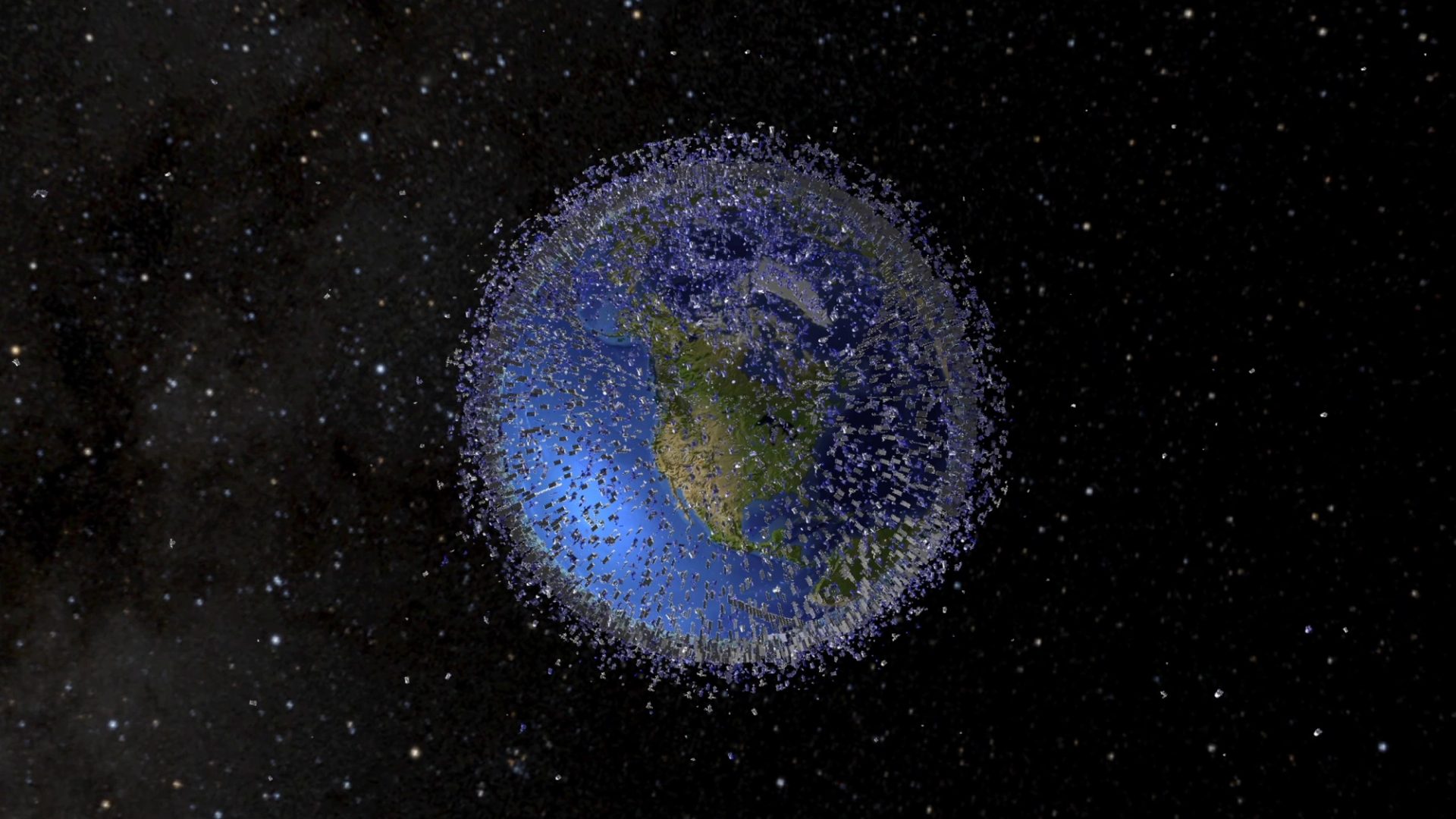

Xin Liu is an engineer and artist. Xin is an artist-in-residence at SETI Institute, an advisor for LACMA Art+Tech Lab, a researcher at Antikythera, Berggren Institute and the founding Arts Curator in the Space Exploration Initiative at MIT Media Lab. Liu’s work explores her interests in the verticality of space, extraterrestrial exploration and cosmic metabolism. She has performed in zero gravity and sent her wisdom tooth into outer space in work that connected her cultural and family traditions.

‘What we have achieved is magnificent, but it’s also so distant and foreign to our embodied experience of living on the planet.’

Ceridwen Dovey As the arts curator at the MIT Space Exploration Initiative, you're at the forefront of space science. Which new space discoveries are inspiring you as an artist?

Xin Liu I’m fascinated by the fact that Earth is at a different temporal moment compared to other planets in the solar system. So, in a way, we could say that Mars is the future of Earth, which is one of many possibilities. I am humbled by the realisation that life itself is such a unique moment in the history of our universe; a fleeting and beautiful moment that is ephemeral at the cosmic scale.