Safe Carriage: Moving an Icon

‘We did it quietly, efficiently, safely. And the more we keep quietly, successfully doing these things, hopefully the more people will realise how much we understand and care for our objects.’

As part of the project to relocate more than 3000 museum objects ahead of the $300 million heritage revitalisation of Powerhouse Ultimo, the moving of Locomotive No. 1 became a priority task and key challenge for Charm Watts, manager of Collection Logistics at Powerhouse. Here the story of its recent journey to Powerhouse Castle Hill is recounted by Watts, as told to Powerhouse senior editor Michael Fitzgerald.

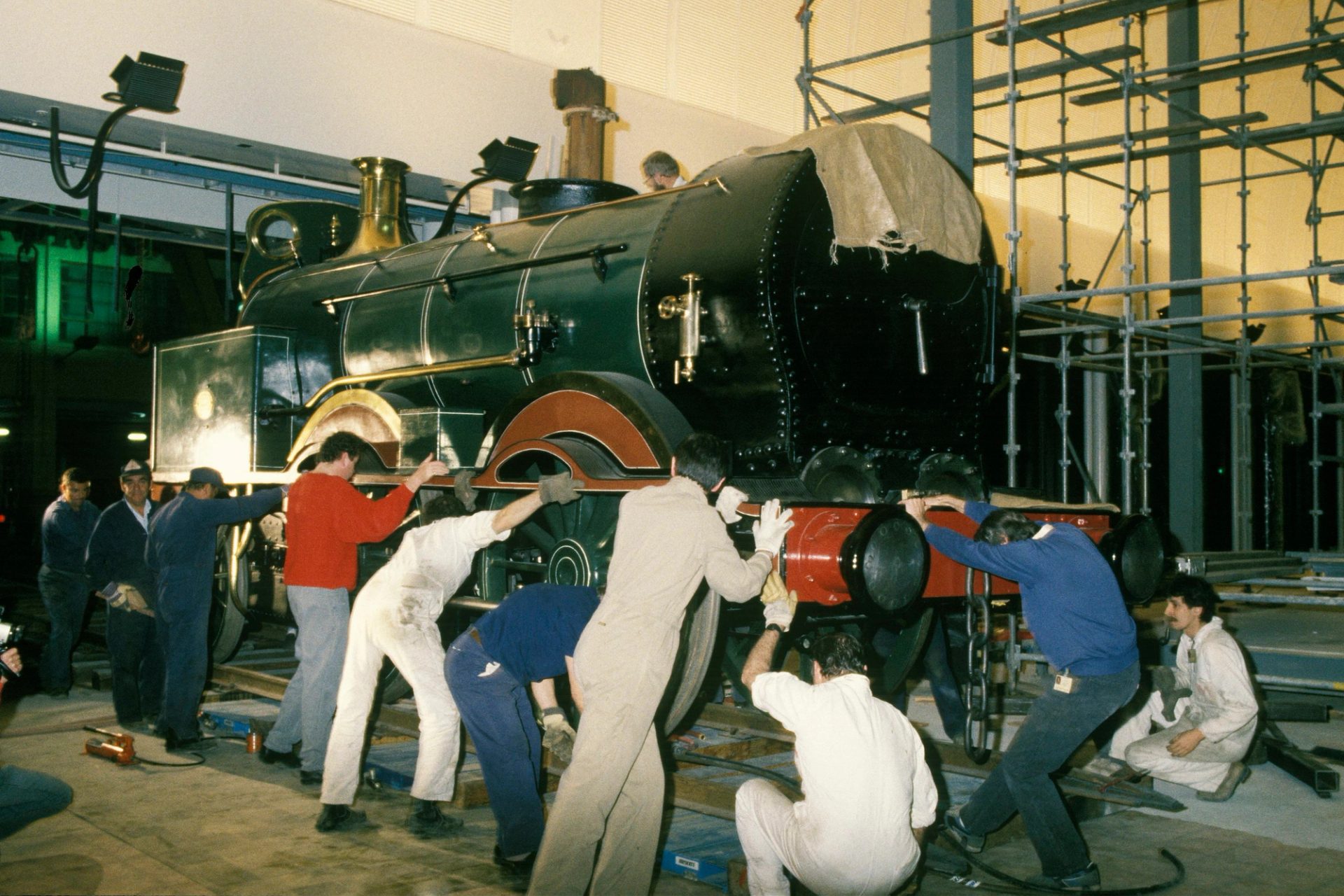

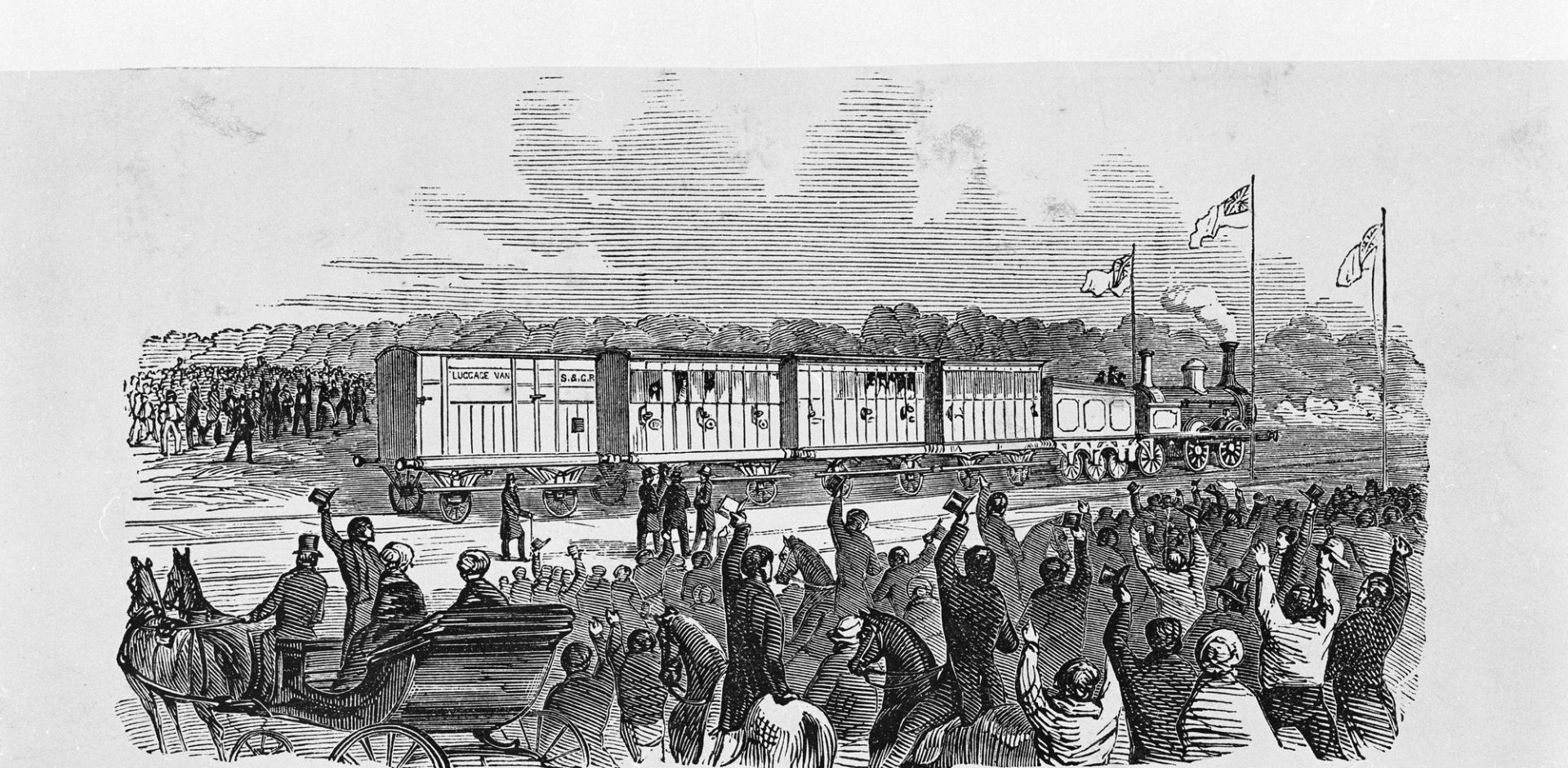

When Locomotive No. 1 arrived from England on board the John Fielden in 1855, it took a team of 20 horses to haul the 46-tonne engine and tender from Circular Quay to Slade’s paddock near the old Eveleigh railway workshops. Then during its 22 years of operation as the locomotive of New South Wales’ first passenger train, No. 1 seemed to move effortlessly from under its cloud of steam. In retirement it moved a further four times for public display before being lowered by air skates into the Wran Building for the opening of Powerhouse Museum in 1988, unveiled in its newly restored livery of Brunswick green, red and black. For the next 36 years, it appeared immovable as the Ultimo museum’s iconic and unofficial mascot.

But on a cold winter’s night on 18 July 2024, No. 1 was set in motion again, in an elaborate logistical exercise that saw the locomotive dispatched 27 kilometres to its new home at Powerhouse Castle Hill. In lieu of the 20 horses that carried it in 1855, the brunt of the heavy lifting in the final stages of its latest journey was provided by a tiny red motorised trolley, just 140 centimetres in length. ‘I call it the Red Radio Flyer,’ says Charm Watts, manager of Collection Logistics at Powerhouse. ‘It’s all electric, and we use it to tow aircraft, trains, cars, anything. It’s pretty fabulous.’