Hard Read

From heartbeats to brainwaves, economic cycles to cosmic orbits, oscillations can be found everywhere. This podcast takes artists and listeners deep into the Powerhouse Collection of half a million objects to unearth stories about the vibrations, fluctuations, and movements woven through our world – and beyond it.

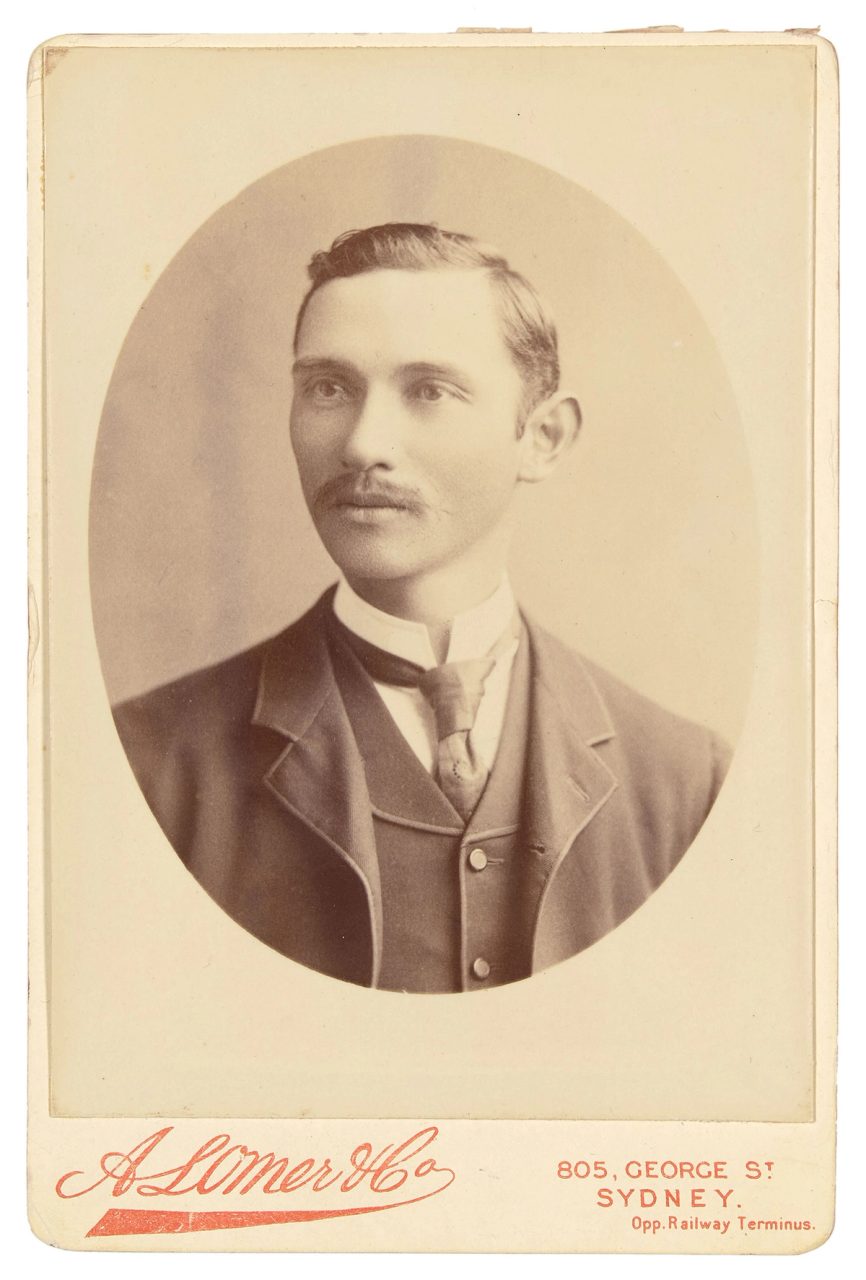

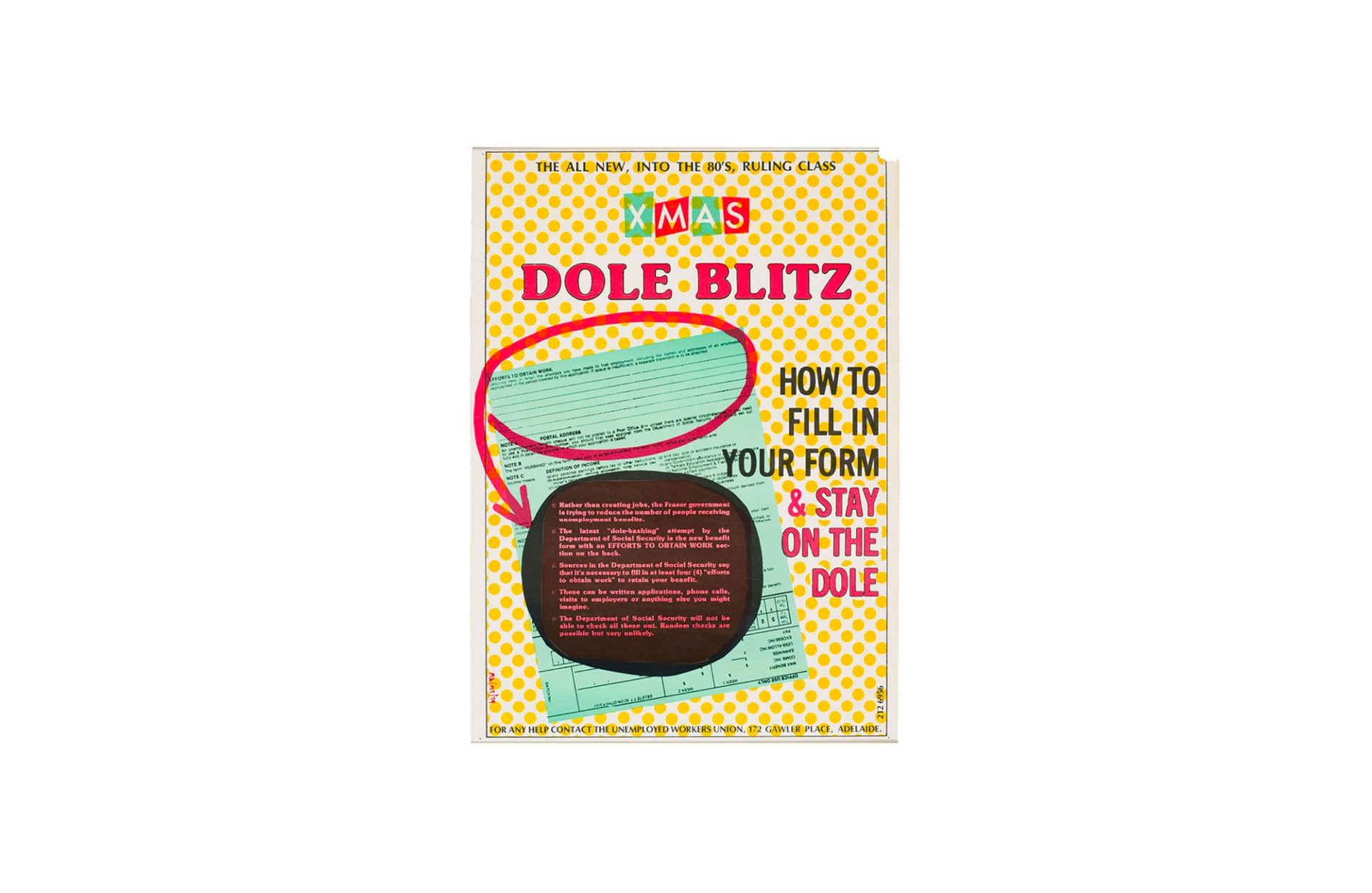

What does it cost to be visible? Chinese and trans people shift in and out of focus in Australia’s historical records – appearing and disappearing, code-switching, oscillating. Through the lens of turn-of-the-century portrait photography, Jinghua Qian looks at the privilege and burden of representation and the luminous power of inscrutability.

‘I fought hard for the slippery shamelessness of my life, and I don't want it displayed in a box with a tidy explanatory text. I want to imagine that every day I can wake up and become something I've never seen.’

Transcript

Chorus Broad. Normal. Hair: thin on top of head. Face: pockmarked. Two scars in the centre of chest, just below nipple line. Complexion: sallow. Build: stout. Small feet. Special features: bird outside left forearm, Japanese girl and flowers inside left forearm. Religion: Pagan religion. Colour of hair: black. Religion: Roman Catholic. Colour of eyes: Black. Eyes: brown. Eyes: brown.

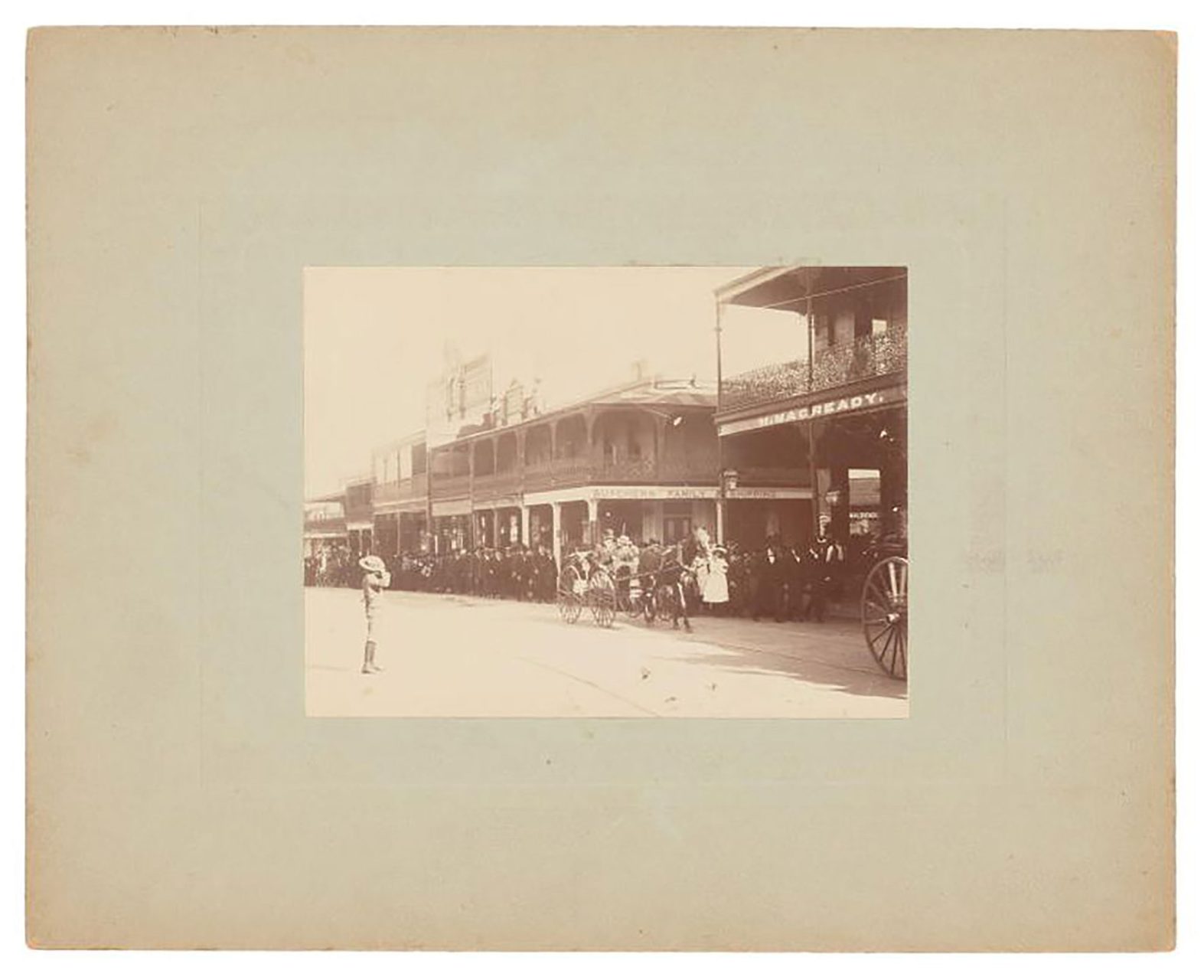

Jinghua Qian That's how Chinese Australians were described in late 19th and early 20th century official records. So many of the photographs we have of Chinese Australians in this era are portraits taken in interactions with police, prisons and border control. The White Australia policy in particular produced a treasure trove of photographs. State surveillance of our ancestors then becomes an uncomfortable perk for our research now. There's no shortage of material. And the portraits themselves are arresting, even if the circumstances are enmeshed with capture and control. There are so many tiny, suggestive details, the glint of a watch chain tucked into a tailored pocket. The scruffy mullet left behind after lopping off a braided cue. Dark eyes stare back through my bright screen.