Carved, Hewn, Encoded

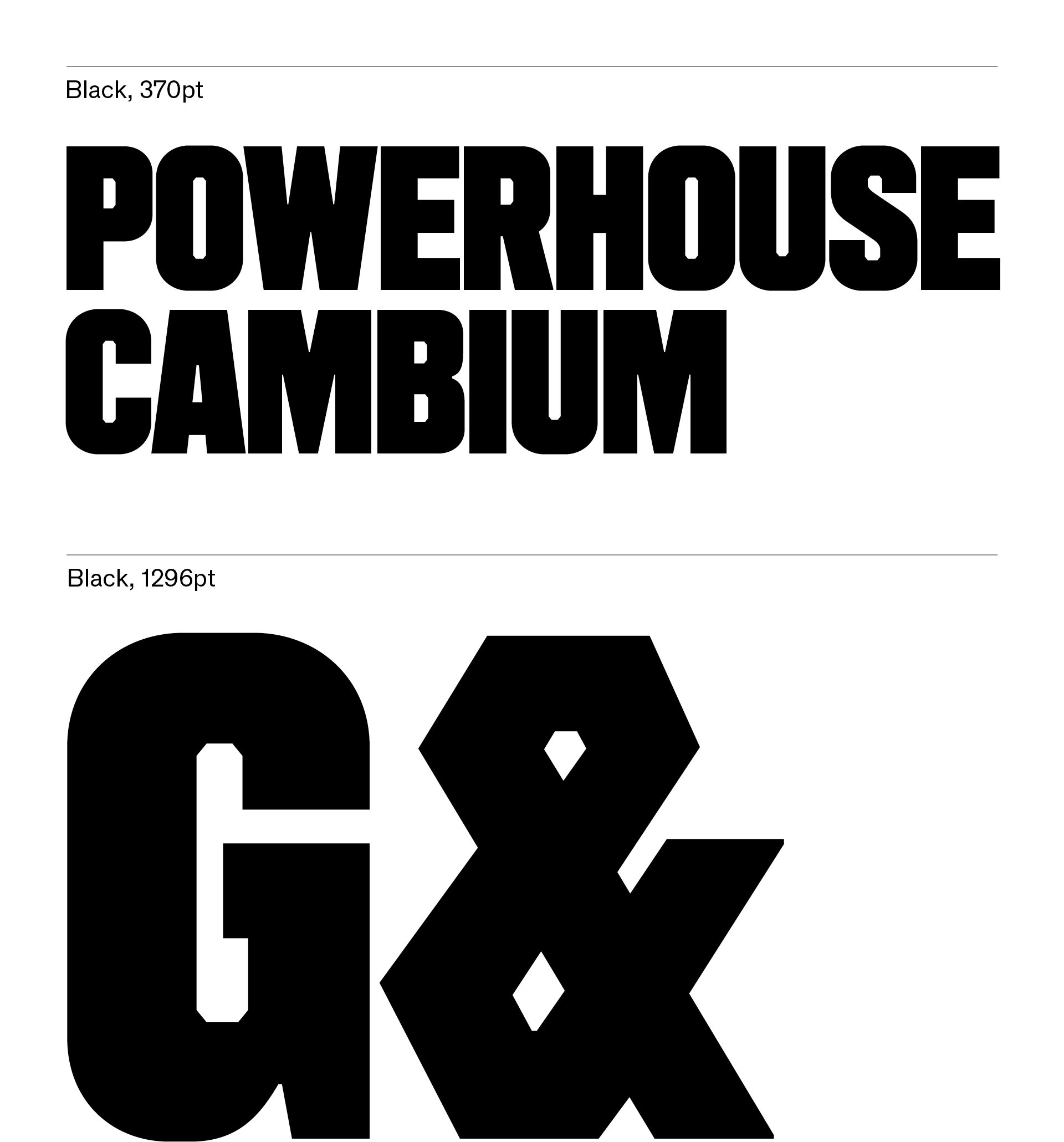

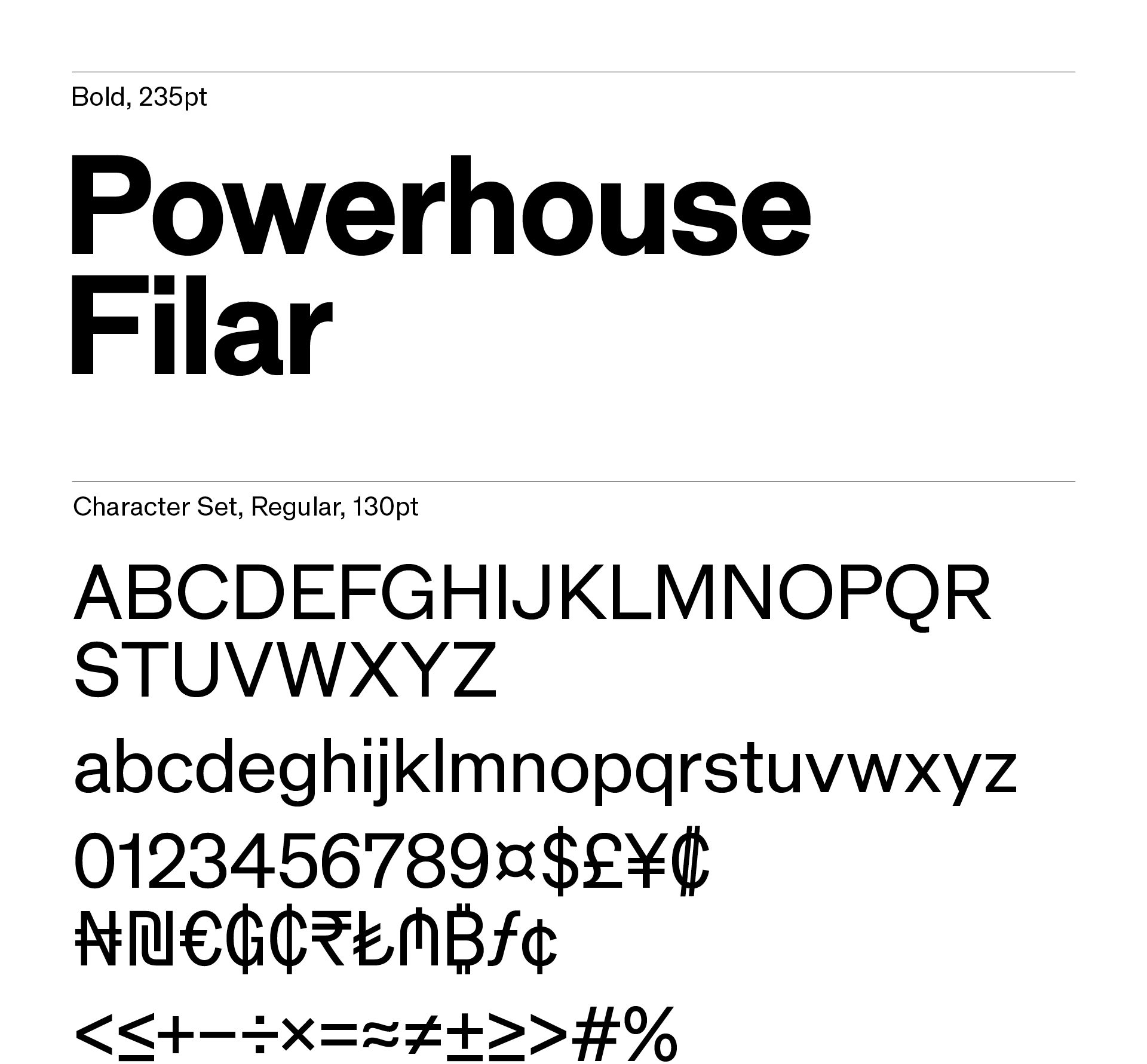

In 2023 Powerhouse commissioned a set of custom typefaces as part of its expansive revitalisation project and reinvigorated identity.

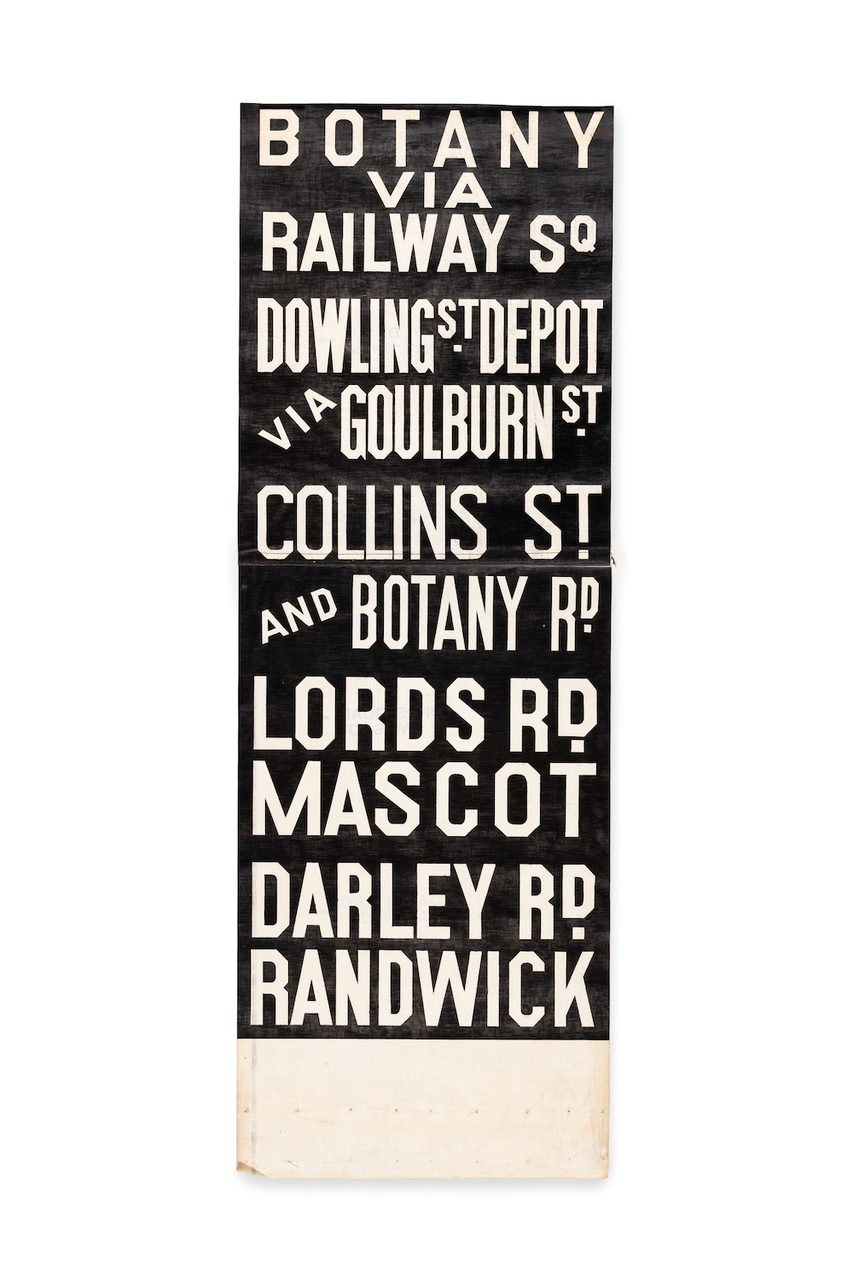

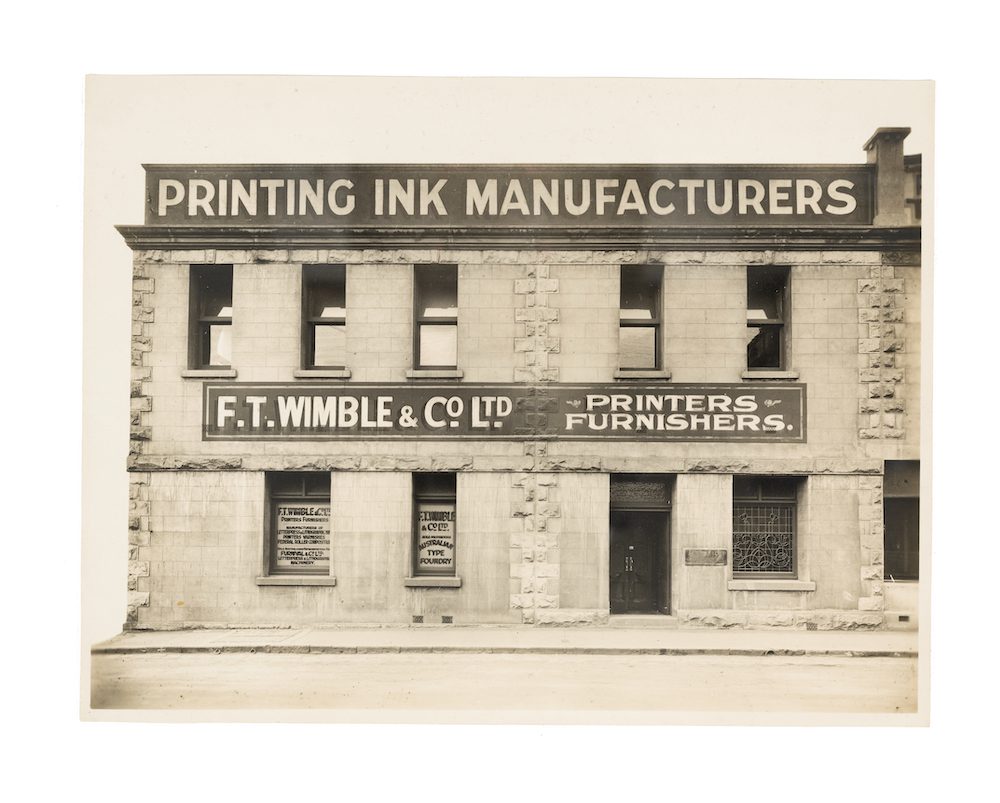

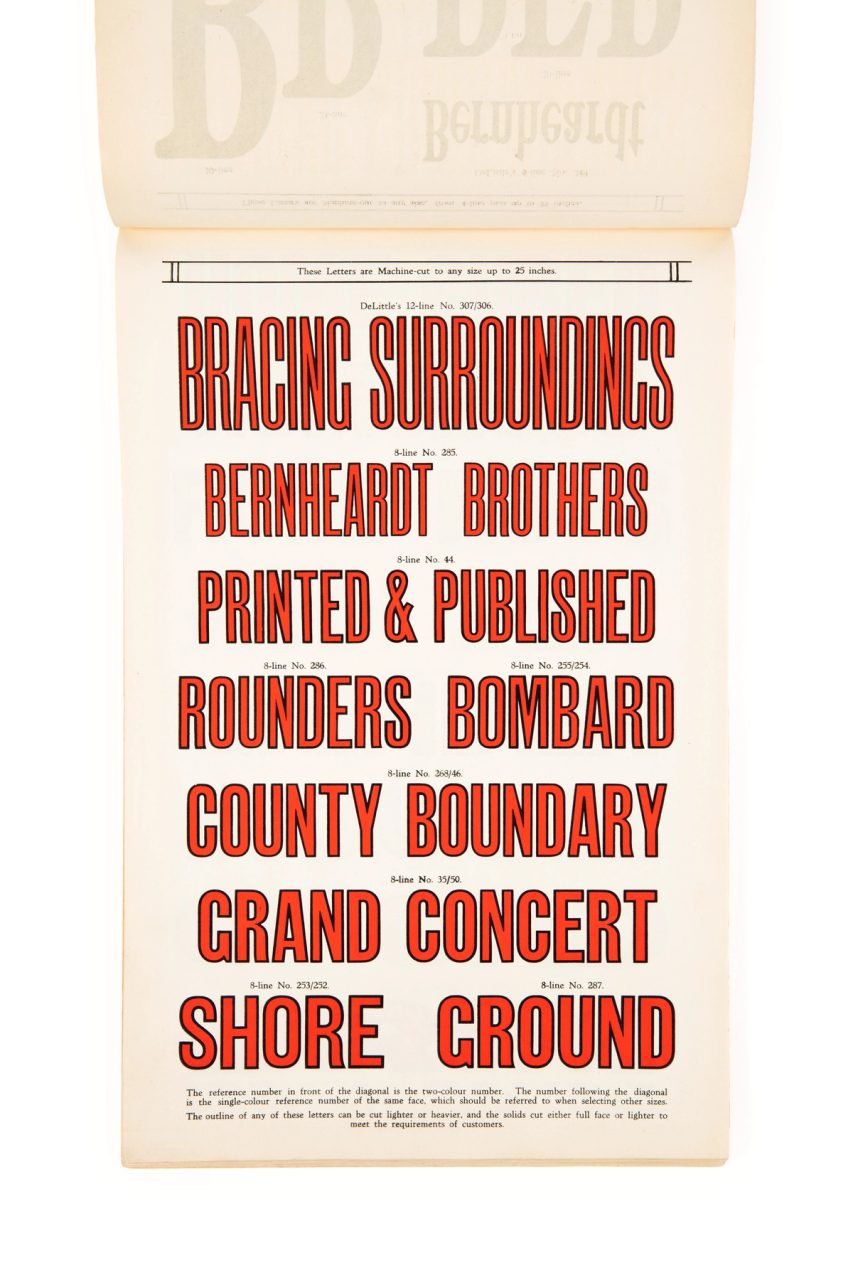

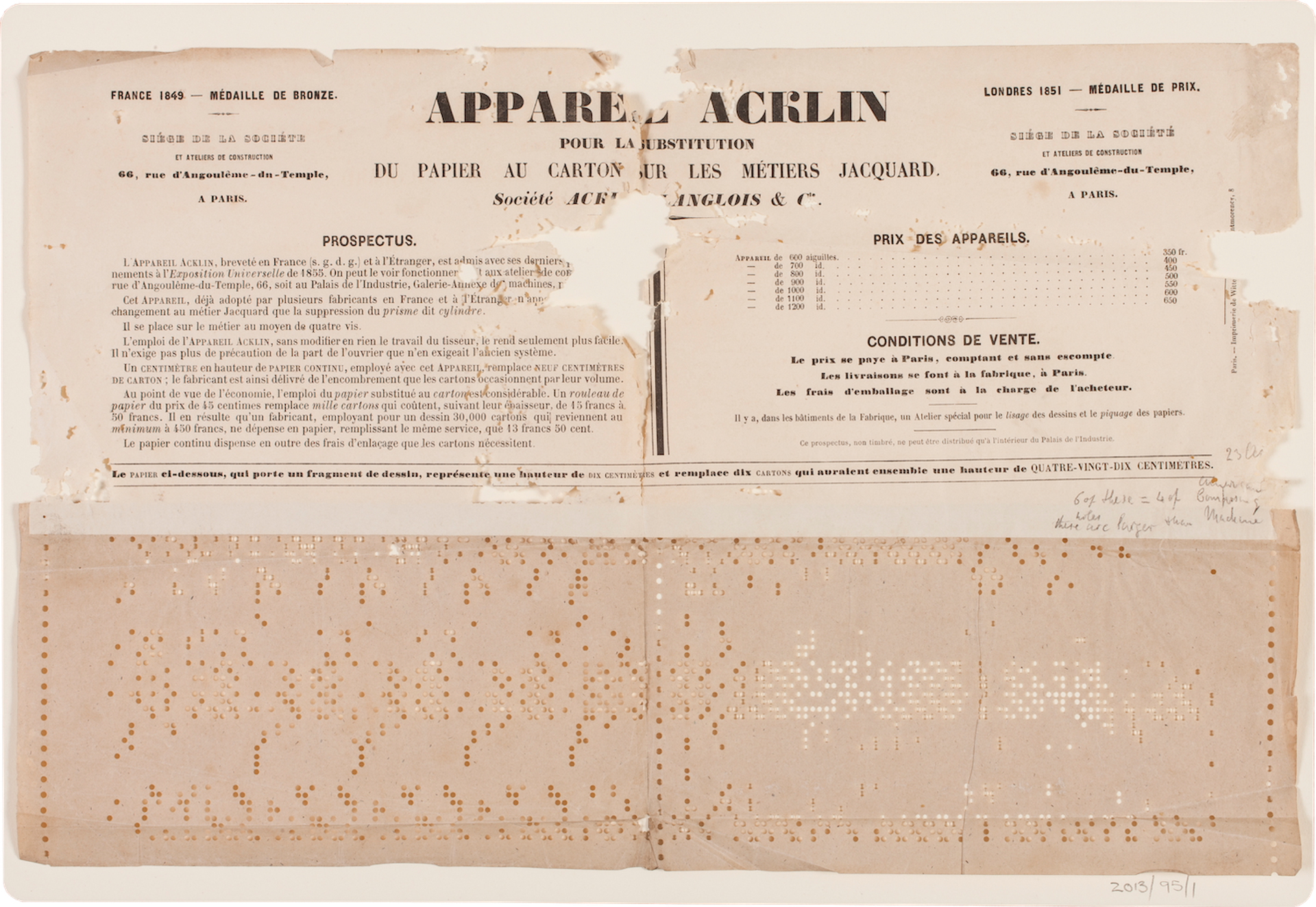

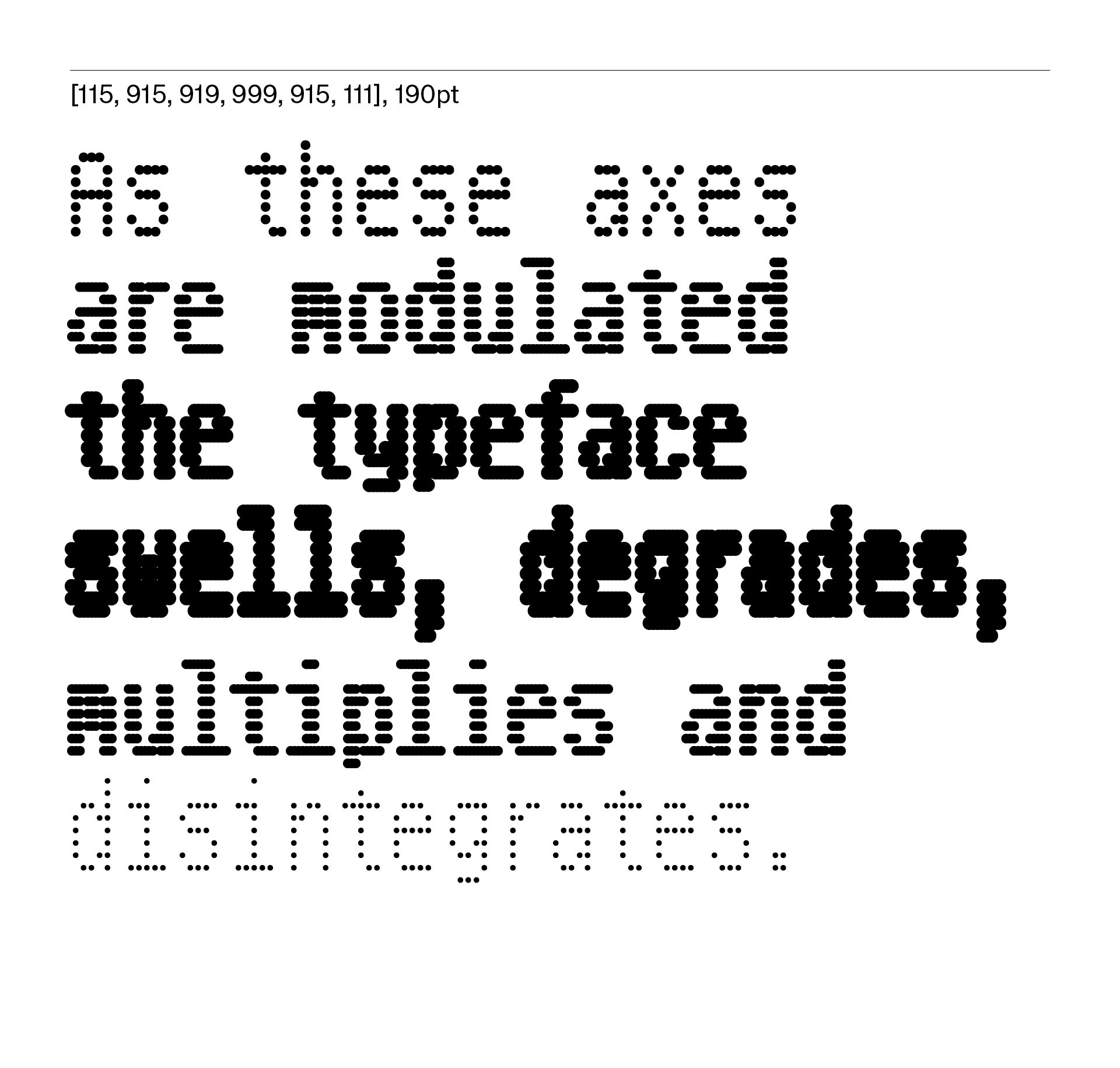

Matter of Sorts conceived and drew new fonts under the direction of Studio Ongarato with the input of chief executive Lisa Havilah and artistic associate Agatha Gothe-Snape. The resulting three custom typefaces – Powerhouse Cambium, Powerhouse Punctum and Powerhouse Filar – found their roots in the vast array of industrial artefacts in the substantial Powerhouse Collection. They draw upon various objects across numerous industries, traversing disparate technologies and time, each contributing a distinct texture to a new typographic palette. They can be understood as a reflection of three kinds of materiality evident in the history of type: metal, wood and the digital, or perhaps through the specific gestures required to bring these letterforms to life: carved, hewn and encoded. This is the recounting of their development.

Powerhouse Cambium

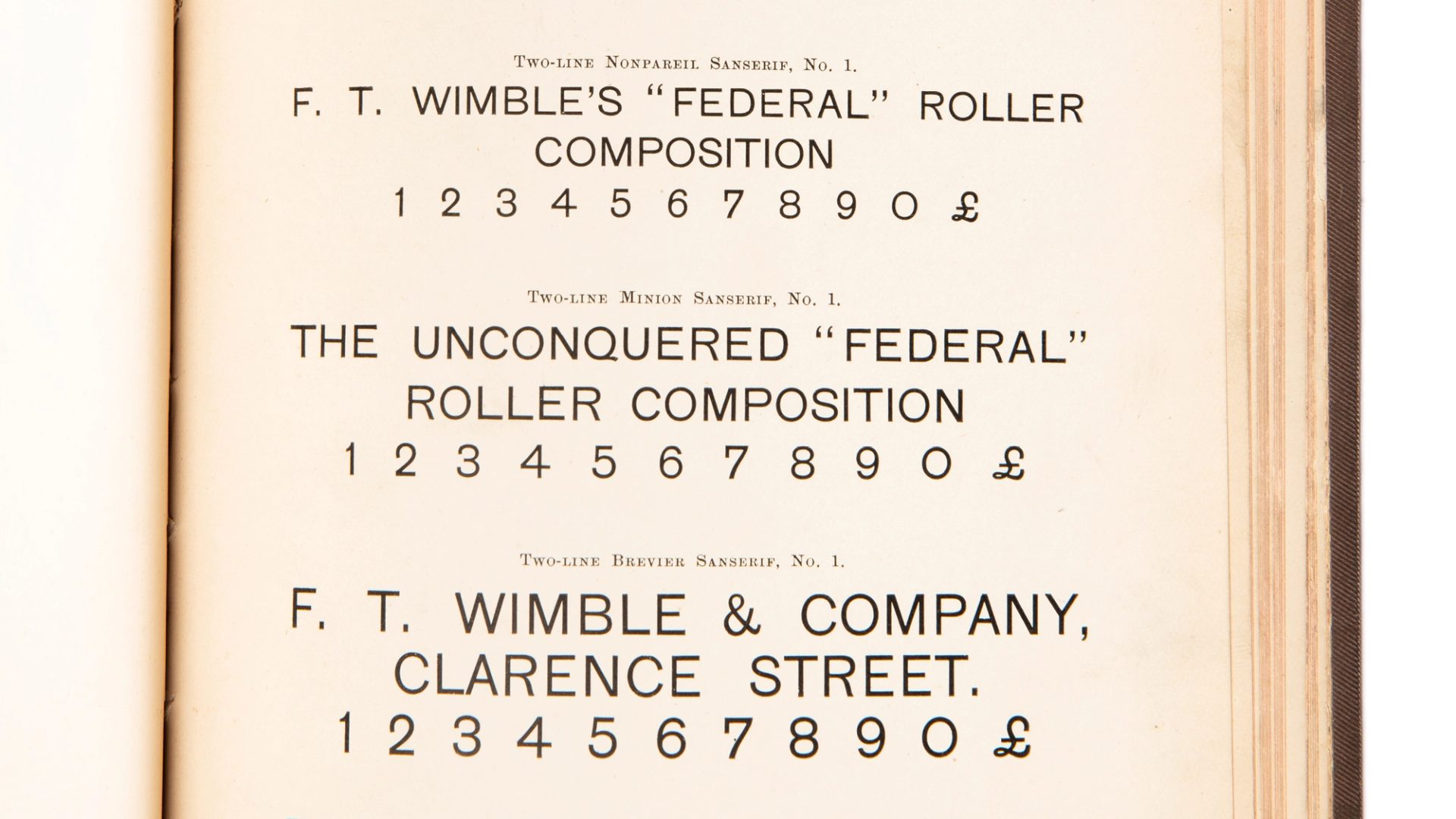

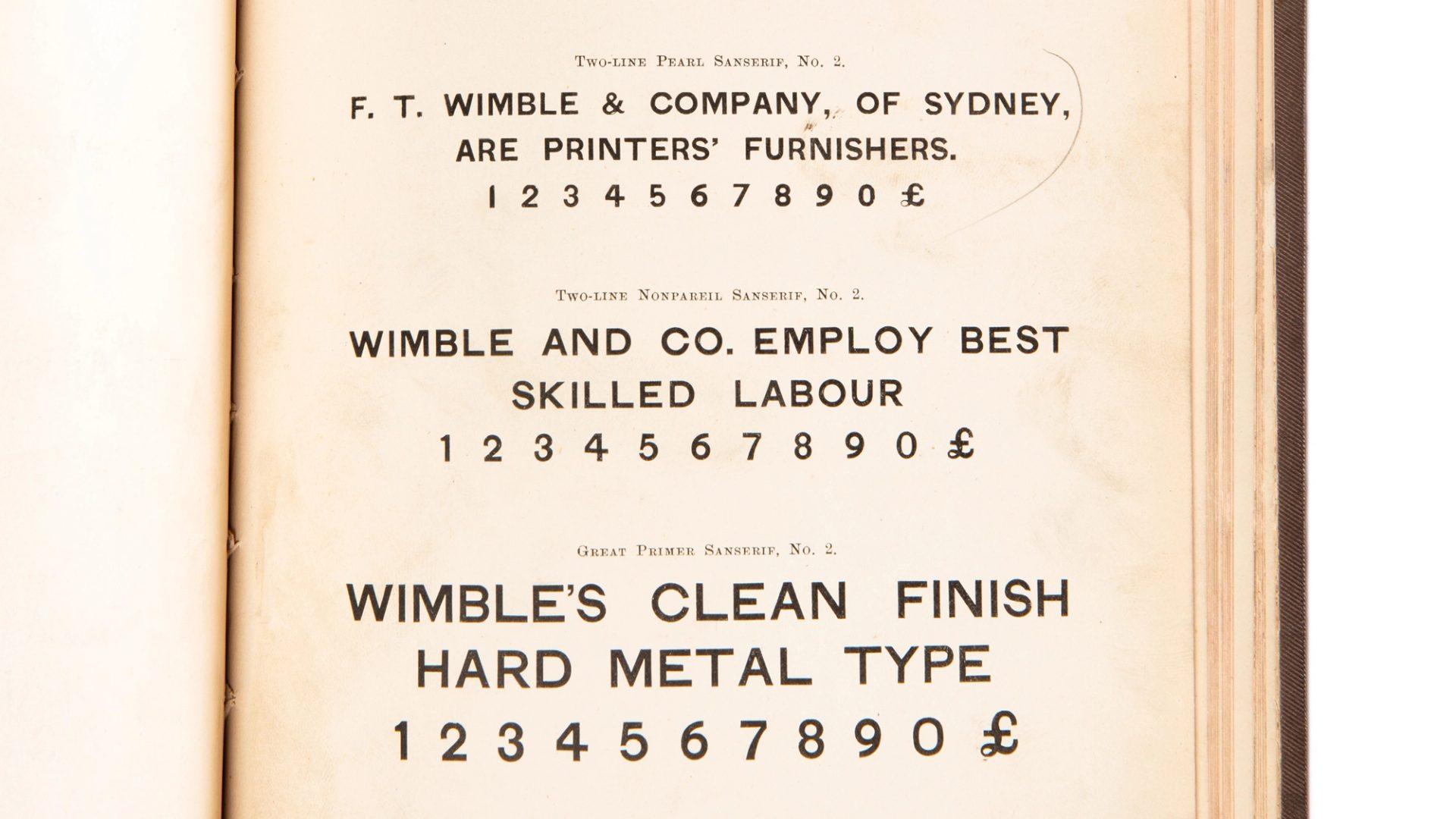

The primary typeface, used to render the logotype, required a substantial presence and some notion of visual distinction. There were various candidates from the collection that suited this brief. Studio Ongarato started the process with some sketches based on a font by the influential US designer Morris Fuller Benton. It features rectangular counterforms – a dissonant detail at odds with its round exterior contours – and a rationalised, simplified construction.